SUCUMBIOS, Ecuador — In the Amazon region, time has a different meaning than most places in the world. People rarely agree to meet at a specific hour, instead dividing the day simply into morning, afternoon or night. Similarly, distance is often expressed in terms of the days it takes to walk from A to B: “It takes 12 days to get to the city,” or “the next settlement is three days from here.”

The argot reflects the social realities of a place where roads, transportation, electricity and running water are all scarce.

Yet wherever there are pathways through the jungle, at least in the Ecuadorian state of Sucumbios bordering Colombia, there also seem to be oil pipelines, some of which were built over 40 years ago and have had little to no maintenance ever since. Spills are common, causing lasting environmental damage.

Crude oil burns all the vegetation it touches, pollutes nearby sources of water used by humans and animals alike, and, many times, the oil seeps into the ground, rendering it infertile. In addition, there are close to 400 chimneys constantly flaring gas, killing anything that dares get close – including, for instance, bugs trying to climb a tree some 10 feet away from three such smokestacks.

Even when the flame is not visible, the gas is still there, belching out onto nearby communities with little real monitoring or control.

In many ways, this liquid gold runs through an artery of death in the Amazon, killing the life it touches and bringing few benefits to the people who live here. Most oil companies import their own workers, so the industry doesn’t even provide jobs to local farmers whose lands are now tainted.

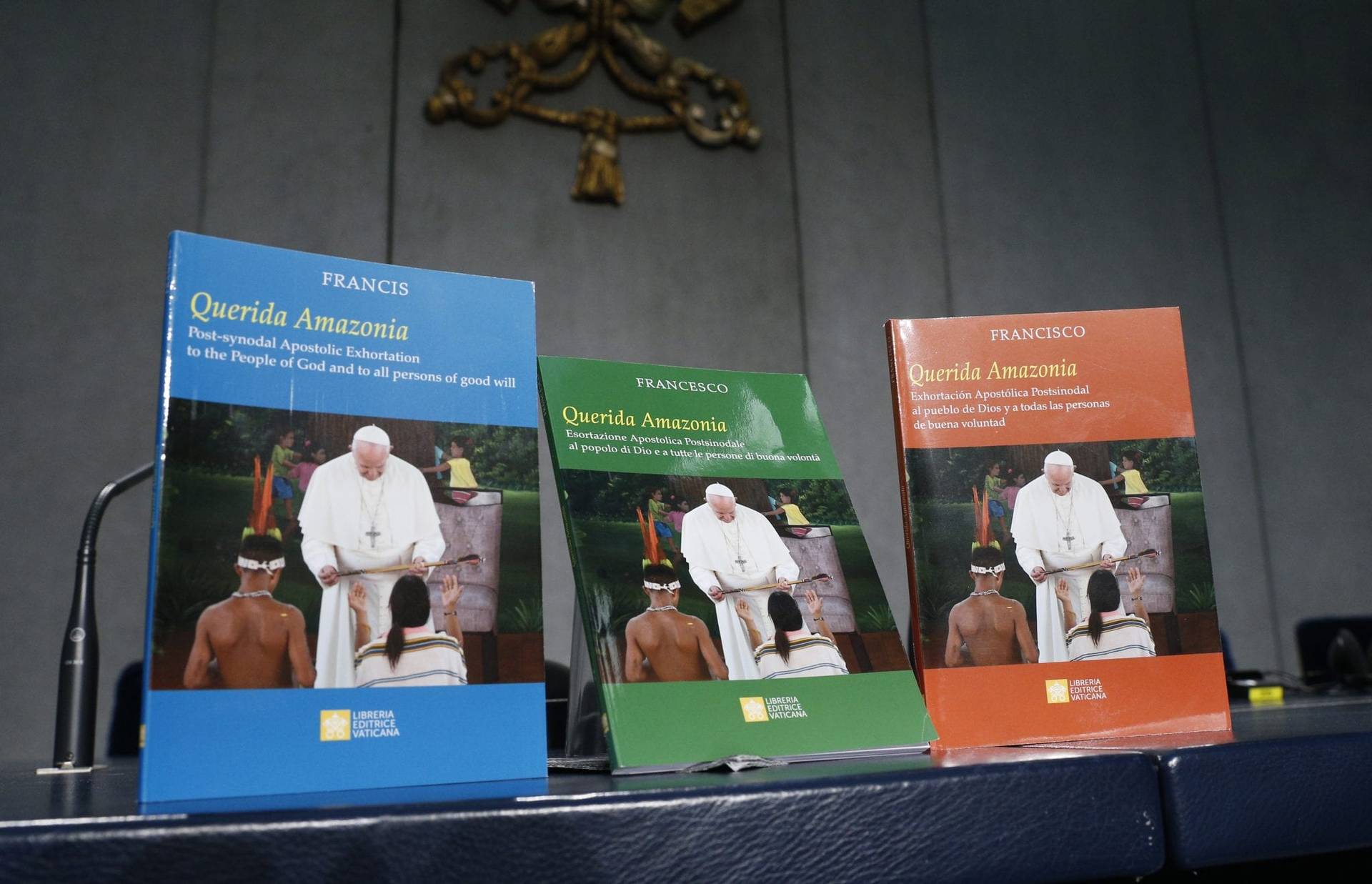

These are the social realities likely to loom large next month in Rome, when Pope Francis convenes an Oct. 6-27 Synod of Bishops on the Amazon. The summit is intended to shine a spotlight on both the rainforest itself as well as the struggles of the people who live within it.

Yolanda Herrera Sanza grew up in a small farm in the village of Pacayacu. Her parents, who are still alive, used to grow cacao and coffee and even had six pools with fish. Yet one night, when they were out some 30 years ago, the national oil company Petroamazonas built two oil wells on their land.

Since then, nothing was the same.

“The government used to say that even though people owned the land, the state owns what lies underneath, so they could come and build a well,” she explained.

“As farmers, oil has meant nothing good for us. My mother has cancer, and my father has a hearing disability due to the constant noise from the oil production,” Herrera said.

“We’ve experienced in the flesh the impact of the pollution this industry leaves,” she said. “Oil has benefited the Ecuadorian state, but not my parents. They used to have livestock, now they have no animals left.”

A recent law is supposed to afford those who live in the Amazon compensation for illnesses and pollution directly related to the oil industry. However, little seems to have been done to prevent such tragedies: Just four months ago, an oil spill killed several farm animals and polluted the local water again.

The state-owned company responsible for the spill simply removed the soil visibly impacted by the oil, leaving a large plot of pasture empty, and did little to nothing to clean the small river that’s nearby on the farm of the Herrera family.

The compensation for the 11 families affected by the spill was a gallon of water every eight days, from which the families are supposed to drink themselves and also water whatever animals they might still have.

Drinking from the river isn’t an option, since its water is now fatal for humans and livestock alike.

The May 15 incident was the third in less than two years. But this time something was different: The community has a newly elected county executive, Flor Jumbo, who’s not afraid of challenging the state to help families at least receive the compensation which, by law, they’re owed.

Jumbo told a group of journalists, including Crux, that by denouncing what is going on, they are “defending the right to life.”

In the state of Sucumbios, 10 out of every 100 people have cancer, and three in four are women. There are no specialized healthcare centers in the region, so to receive treatment, people have to go to Quito, which is some 6 hours away by car.

“Cancer is a death sentence,” Jumbo said.

The government and oil companies refuse to acknowledge the emergency, she said, yet when people try to sell their livestock, they get less money because it’s allegedly tainted. Those who live in Pacuyacu can’t even donate blood: it too, they’re told, is polluted.

“People are afraid to speak up, but we’ve told them that they have to,” Jumbo said.

One especially sad irony, she said, is that most local farmers end up “begging for a job from the same [oil companies] who killed the life around them.”

The Catholic Church has long played a key role in this region, speaking up against the environmental impact of extraction and other polluting agents, such as glyphosate, a herbicide used by the Colombian government to kill cocaine plantations.

Facing a chronic shortage of priests, laity and religious sisters carry much of the load here.

One example is Daniel Valladolid, whose day job is farming. He doubles as a pastoral agent and a minister for the Eucharist, coordinating with the one priest in the region to guarantee that he’ll come at least once a year, often around a major feast such as Christmas or Easter.

Like Jumbo, Valladolid encourages people to speak up. He has a reputation for always being available to lend a helping hand.

“A true Christian walks with both feet: Evangelizing, praying and sharing the Word of God, but also aiding those in need,” said Valladolid, who barely finished primary school.

Sister Nelida Velasco of the Marian Sisters of Jesus, an order born in Ecuador, helped coordinate the meeting with Jumbo, Herrera, and other families affected by the May spill.

As one of those gathered said in passing, with tears in her eyes, the small community of four nuns has been a “constant presence” during times of desperation.

The sisters cover a seemingly endless ground of remote villages, either on foot or relying on the good will of drivers passing by. In a land where a gallon of water costs the same as a gallon of gas, they’ve tried for years to come up with the $10,000 needed to buy a car, but so far to no avail.

Follow Inés San Martín on Twitter: @inesanma

Crux is dedicated to smart, wired and independent reporting on the Vatican and worldwide Catholic Church. That kind of reporting doesn’t come cheap, and we need your support. You can help Crux by giving a small amount monthly, or with a onetime gift. Please remember, Crux is a for-profit organization, so contributions are not tax-deductible.