Today is one of those rare occasions when a pope takes part in a liturgy in St. Peter’s Basilica, but it’s basically a non-speaking part. The honor of delivering the sermon, like every Good Friday, falls to the Preacher of the Papal Household, who, for the last 27 years, has been Capuchin Father Rainero Cantalamessa.

For people tuning into the Good Friday service each year, it’s always a bit jarring to see the pope sitting down listening rather than standing up himself and preaching, which generally leads to the following three questions:

- What is the office of the Preacher of the Papal Household?

- Who is Father Rainero Cantalamessa?

- If the pope’s not preaching, does it really matter?

Preacher of the Papal Household

Pope Paul IV (1555-1559) created the office of “Apostolic Preacher,” meaning someone designated to preach for the pope and senior Vatican officials – in fact, what’s today called the Preacher of the Papal Household is the only cleric in the Catholic Church allowed to preach to the pope.

Since 1753, the office has been reserved to the Capuchin Franciscans because of what Pope Benedict XIV described as “the example of Christian piety and religious perfection, the splendor of doctrine and the Apostolic Zeal” found in the order.

(For the record, I was educated by the Capuchins and still see them as my spiritual fathers, so exactly how deep their “piety and perfection” runs may be a matter of some contention.)

Initially, the office of Preacher of the Papal Household was unpopular within the Roman Curia, since part of the idea was to remind the cardinals and other senior officials of their duties and to rap them on the knuckles if they were falling short. Over time, however, the role evolved into delivering general spiritual meditations to the pope and his aides, usually tied to the liturgical season.

Though serving as Preacher of the Papal Household is certainly a privilege, it’s not a full-time job. Whoever holds the position is responsible for leading retreats for the pope and senior Vatican officials during Advent and Lent, as well as delivering the Good Friday homily in St. Peter’s Basilica, but otherwise is not a Vatican official, is free to engage in other pursuits, and has no role in the governance of the Church.

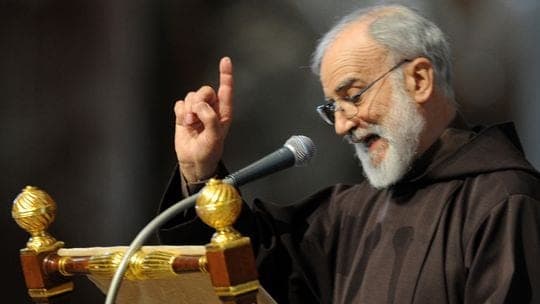

Father Rainero Cantalamessa

Cantalamessa, who will turn 83 in July, has held the role of Preacher of the Papal Household since 1980, meaning he’s given multiple sermons before three popes – John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and now Francis. (Of John Paul, Cantalamessa says that during the entire 25 years he served him, the pope only missed two sermons, during a trip to Latin America – and when John Paul returned, he said, he promptly sought out Cantalamessa to apologize.)

Cantalamessa is involved in the charismatic movement in the Catholic church, writing books and giving conferences and retreats on the gifts of the Holy Spirit. When he’s not sermonizing before the movers and shakers in the Vatican, Cantalamessa is, in effect, an itinerant preacher, moving around the globe in his simple brown Capuchin habit, clutching a tattered small blue copy of the New Jerusalem Bible.

It was in New Jersey in 1967 that Cantalamessa was first “baptized in the Spirit,” a key term in Charismatic Christianity for a decisive moment in which someone accepts Jesus Christ in a deeply personal way. He once explained that his experience shocked his friends in Italy, because early on he was an “adversary” of the charismatic movement.

“When I got back to Italy, they told me, ‘We sent America Saul, and they have sent us back Paul,’” Cantalamessa joked.

Since then, Cantalamessa has gone on to become arguably the most prominent adherent of the Charismatic movement in the Catholic Church.

Euphonically enough, his last name in Italian means “sing the Mass.”

Cantalamessa, however, is not the stereotypical enthusiast associated with the Charismatic scene. He’s low-key, and just as likely to cite Thomas Aquinas as he is to quote hymns or to invoke wonders. Yet he’s committed to seeing Christianity not in terms of formal adherence to a Creed, but as a personal decision to “accept Jesus Christ” and to receive “baptism in the Spirit.”

Though he holds advanced degrees in both classical literature and theology, Cantalamessa is comfortable with the language of “revivalist” Christianity, which makes him a natural interlocutor with many Protestants, especially Pentecostals.

In June 2006, for instance, Cantalamessa traveled to Argentina for a joint Evangelical and Catholic prayer service, where he was joined by the Archbishop of Buenos Aires at the time, Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio – the future Pope Francis.

Why it Matters

Granted, having anyone other than the pope take the microphone in St. Peter’s Basilica automatically reduces the news value. On the other hand, since this is the only cleric in the world permitted to preach to the pope, it’s not just your ordinary homily either.

Over the years, Cantalamessa has sometimes used his platform to raise issues, push the envelope, and generally go well beyond pious platitudes to get people thinking and talking.

At the time Good Friday rolled around in 2002, Catholicism’s attitude toward other world religions was a front-burner topic due to a September 2000 document Dominus Iesus, issued by then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which asserted that non-Catholics are in a “gravely deficient position,” and urged strong new evangelizing efforts.

While acknowledging that one must avoid relativism, or the attitude that one religion is as good as another, Cantalamessa told his audience, which included John Paul II and Ratzinger, that conversion of heart is a far more important objective than conversion of creed. It’s more important to help people in their walk with God, he suggested, than to sell them on a particular brand in the religious marketplace.

“It is more important that men and women become holy,” Cantalamessa said, “than that they know the name of the one Savior.”

In December 2006, Cantalamessa delivered an Advent meditation before Pope Benedict XVI in which he suggested holding a day of fasting and penance for crimes of child sexual abuse committed by Catholic clergy. While such liturgies have become common in many places around the world, eleven years ago it was still a fairly daring idea to float, especially in that setting.

Four years later, however, Cantalamessa came back to the sexual abuse scandals, this time implying that widely critical media coverage amounted to a form of anti-Catholicism, which, in his words, bore comparison to “more shameful aspects of anti-Semitism.” When backlash ensued, Cantalamessa insisted he was quoting from a letter from a Jewish friend, but a Vatican spokesman nevertheless felt compelled to declare that Cantalamessa was not speaking officially for the Catholic Church.

On Good Friday in 2014, Cantalamessa’s most interesting comment came in a brief meditation on Judas’s eternal destiny. He said it’s legitimate to hope that in his final moments Judas repented and was saved. More broadly, Cantalamessa hinted that it’s legitimate to have the same hope for everybody, meaning to hope that while Hell is real, it’s also basically empty.

“The Church assures us that a man or a woman proclaimed a saint is experiencing eternal blessedness,” Cantalamessa said. “But it does not itself know for certain that any particular person is in Hell.”

Given that the question of whether Hell might be empty has been a bone of contention in Catholic theology since the time of famed Swiss theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar in the 1970s and 80s, the statement amounted to Cantalamessa gently taking sides in an on-going debate.

For all those reasons, while it may not be the pope, Catholic ears still tend to perk up whenever Cantalamessa takes the stage.