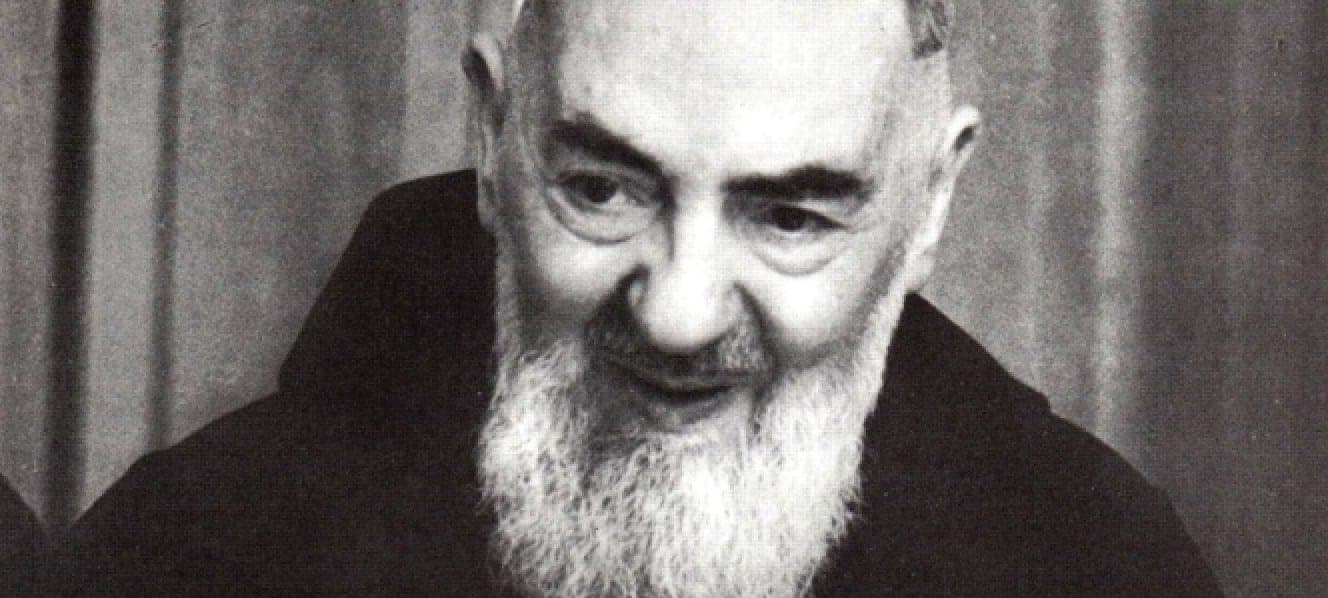

Today marks the close of a jubilee year dedicated to Padre Pio, now formally known as Saint Pio of Pietrelcina, the great 20th century Capuchin mystic, stigmatic and healer. The jubilee began last July 28, which marked the 100th anniversary of his arrival in San Giovanni Rotondo, the small town in the Italian province of Foggia where he would spend the rest of life, eventually founding not only a major hospital but a spiritual empire.

Italian Cardinal Angelo Amato, Prefect of the Vatican’s Congregation for the Causes of Saints, is heading to San Giovanni Rotondo for the occasion to preside over two events – a memorial Mass and the dedication of a new “Place of Memory,” intended to keep the saint’s legacy alive.

At one level, it’s easy to think that Padre Pio isn’t exactly the ideal saint to promote under Pope Francis.

To begin with, Francis isn’t St. Pope John Paul II, who had a mystical streak a mile wide, and who found the supernatural phenomena surrounding Padre Pio electrifying. Francis has more of a down-to-earth spirituality, and while he doubtless accepts the possibility of inexplicable gifts such as the stigmata (the spontaneous appearance of the five wounds of Christ in one’s own body) or bilocation, equally probably, they aren’t the first thing he thinks of when he contemplates sanctity.

Moreover, Francis is usually seen as a centrist-to-progressive on many matters, while Padre Pio was a staunch conservative both politically and theologically.

For beginners, Padre Pio celebrated Mass in Latin according to the pre-Vatican II rite his entire life, receiving Vatican permission to continue to do so even after the council. In that sense, he represents a kind of ecclesiastical throw-back that could leave Francis a bit cold.

Further, Padre Pio famously almost never left his friary at San Giovanni Rotondo, but among the rare occasions when he did was to vote for the Christian Democrats, which for most of the 1940s, 50s and 60s, were the conservative bulwark against a Socialist/Communist conquest of Italy.

In his recent book on Padre Pio, Italian journalist Luigi Ferraiuolo documents the depth of that loyalty. He records an episode in which one of Padre Pio’s devotees came to him to complain that she had voted Christian Democrat both in 1948 and again in 1953, and both times she felt they let her down.

Padre Pio’s response? “At least those guys have already fed themselves,” he said. “The ones to come still have to eat.” It was a colloquial Italian way of saying, hey, they may not be perfect, but they’re what we’ve got.

Make no mistake, Padre Pio was serious about politics. He managed to get the Christian Democrats elected in Foggia throughout his life, when in the past the province had voted for liberal parties. A story from 1966, toward the end of his life, is telling. There were two mayoral candidates for San Giovanni Rotondo. Under the rules at the time, the city council was supposed to decide, but it was deadlocked. As a result, they trekked out to Padre Pio’s Capuchin friary to ask him to resolve things.

As Ferraiuolo tells the story, Padre Pio walked into the room and brusquely informed one of the candidates he had to step aside, because his rival was a doctor and director of the Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, the hospital he founded and built into one of Italy’s major clinical and medical research centers. In fact, that rival, Giuseppe Sala, became mayor.

So much, in other words, for Francis’s dictum about priests staying out of politics.

(As a completely gratuitous “Trivial Pursuit” aside, if you’re ever in Italy, here’s a way to impress your Italian friends, all of whom will know of Padre Pio and the Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza. Ask them: “Do you know what other name the hospital once had?” The correct answer is Clinica Fiorello La Guardia, named after the famous Mayor of New York, who in 1946-47 was head of the U.N. Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, responsible for post-WWII reconstruction in Europe, and which in 1948 provided money for construction in memory of La Guardia, whose father had immigrated to the United States from Foggia.)

(Padre Pio personally blessed a plaque naming the hospital in La Guardia’s honor during a 1948 ceremony. During work a year or so later, however, the plaque came down, and everyone forgot about it. Eventually, the name Padre Pio originally gave the project stuck.)

Yet upon closer examination, there are at least three reasons why Padre Pio is actually a terrific saint for the Francis era.

First, Padre Pio incarnates popular religion. He was viewed with deep suspicion by ecclesiastical authorities during his life, including several popes, and investigated multiple times by his own Capuchin order and by the Holy Office, the precursor to the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Yet people kept flocking to him, attending his Masses, asking him to hear their confessions, and just wanting to be in his presence.

At one point, when rumors were swirling that Padre Pio might be transferred, townspeople in San Giovanni Rotondo took up pitchforks and torches and guarded his friary around the clock, to prevent him from being whisked away in the dead of night.

Francis is a pope who believes there’s more wisdom in one popular Marian procession than in a bookshelf full of theological tomes, so he probably smiles every time he contemplates the victory of the vox pop over the elites represented by Padre Pio.

Second, Padre Pio was all about the poor. The point of building the Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza in the first place was to provide the same high-quality medical care available to rich Italians to the poor.

American journalist Barbara Ward captured that side of Padre Pio’s vision.

“Nine tenths of the people who came to Padre Pio were in unrelieved poverty. Poverty was the root of so many neglected diseases, lifelong ill health, crippling blindness, infirmities and miseries,” she wrote.

“That entire tragic load had to be borne by him day after day, from the moment he entered the church at dawn until the last penitents went on their way. Padre Pio was the last man in the world to let his friends forget that Our Lord not only preached to souls, but also healed bodies and promised Heaven to those who feed the hungry and clothe the naked. If there was to be medical care, the hospital needed to be in San Giovanni Rotondo.”

Padre Pio thus shared Francis’s sense that it isn’t enough to preach Gospel values in abstract terms, but they have to be translated into action in the hurly-burly of the here-and-now – and, like Francis, he was awfully savvy about getting it done.

Third, and perhaps most fundamentally, both Francis and Padre Pio are profoundly devoted to mercy.

Legendarily, Padre Pio spent hours every day in the confessional, trying to offer God’s forgiveness to wounded souls. Ordinary Italians of every stripe came to see him as the other face of the Catholic Church – not distant and imperial, but close and feeling their pain. As the descendant of Italians himself, Pope Francis is well aware of that reputation, and of the kind of Church Padre Pio represents in the popular mind.

Given all that, perhaps what the juxtaposition between Padre Pio and Pope Francis really suggests is this: Being a “Francis priest” is less about whether one leans left or right, and more about the fundamental idea of being close to people, especially the poor and the suffering. Whatever political expression those instincts may take is, perhaps, almost after-the-fact.

In that sense, arguably Padre Pio is a perfect embodiment of the Francis ethos, a figure reminding us this isn’t fundamentally about politics but pastoring – and that’s something that won’t be any less true tomorrow than today, as the formal jubilee draws to a close.