Facebook already asks for your thoughts. Now it wants your prayers.

The social media giant has rolled out a new prayer request feature, a tool embraced by some religious leaders as a cutting-edge way to engage the faithful online. Others are eyeing it warily as they weigh its usefulness against the privacy and security concerns they have with Facebook.

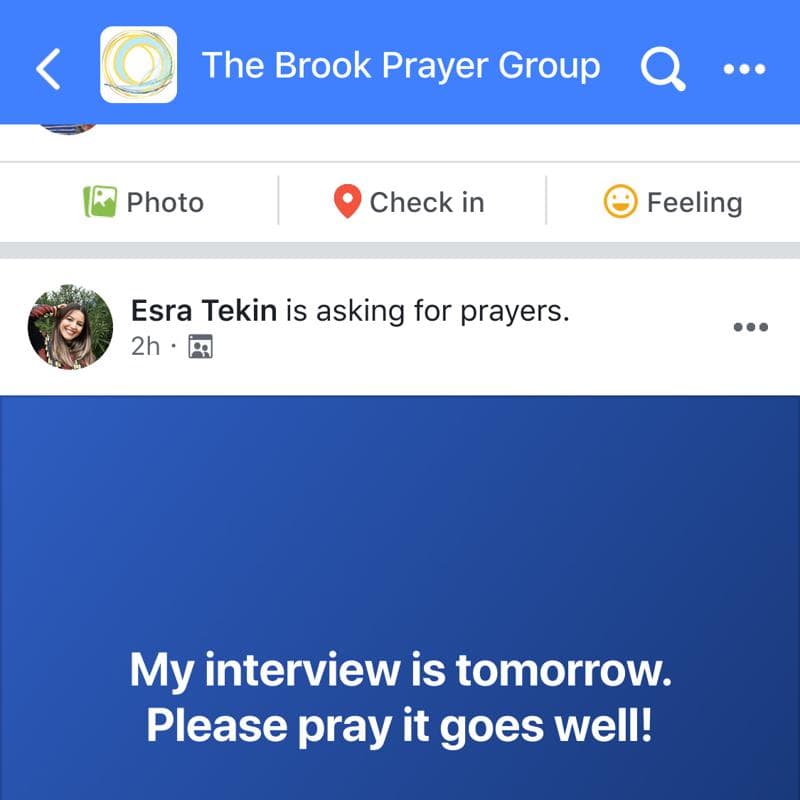

In Facebook Groups employing the feature, members can use it to rally prayer power for upcoming job interviews, illnesses and other personal challenges big and small. After they create a post, other users can tap an “I prayed” button, respond with a “like” or other reaction, leave a comment or send a direct message.

Facebook began testing it in the U.S. in December as part of an ongoing effort to support faith communities, according to a statement attributed to a company spokesperson.

“During the COVID-19 pandemic we’ve seen many faith and spirituality communities using our services to connect, so we’re starting to explore new tools to support them,” it said.

The Rev. Robert Jeffress of First Baptist Church in Dallas, a Southern Baptist megachurch, was among the pastors enthusiastically welcoming of the prayer feature.

“Facebook and other social media platforms continue to be tremendous tools to spread the Gospel of Christ and connect believers with one another — especially during this pandemic,” he said. “While any tool can be misused, I support any effort like this that encourages people to turn to the one true God in our time of need.”

Adeel Zeb, a Muslim chaplain at The Claremont Colleges in California, also was upbeat.

“As long as these companies initiate proper precautions and protocols to ensure the safety of religiously marginalized communities, people of faith should jump on board supporting this vital initiative,” he said.

Under its data policy, Facebook uses the information it gathers in a variety of ways, including to personalize advertisements. But the company says advertisers are not able to use a person’s prayer posts to target ads.

Father Bob Stec, pastor of St. Ambrose Catholic Parish in Brunswick, Ohio, said via email that on one hand, he sees the new feature as a positive affirmation of people’s need for an “authentic community” of prayer, support and worship.

But “even while this is a ‘good thing,’ it is not necessary the deeply authentic community that we need,” he said. “We need to join our voices and hands in prayer. We need to stand shoulder to shoulder with each other and walk through great moments and challenges together.”

Stec also worried about privacy concerns surrounding the sharing of deeply personal traumas.

“Is it wise to post everything about everyone for the whole world to see?” he said. “On a good day we would all be reflective and make wise choices. When we are under stress or distress or in a difficult moment, it’s almost too easy to reach out on Facebook to everyone.”

However, Jacki King, the minister to women at Second Baptist Conway, a Southern Baptist congregation in Conway, Arkansas, sees a potential benefit for people who are isolated amid the pandemic and struggling with mental health, finances and other issues.

“They’re much more likely to get on and make a comment than they are to walk into a church right now,” King said. “It opens a line of communication.”

Bishop Paul Egensteiner of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America’s Metropolitan New York Synod said he has been dismayed by some aspects of Facebook but welcomes the feature, which bears similarities to a digital prayer request already used by the synod’s churches.

“I hope this is a genuine effort from Facebook to help religious organizations advance their mission,” Egensteiner said. “I also pray that Facebook will continue improving its practices to stop misinformation on social media, which is also affecting our religious communities and efforts.”

The Rev. Thomas McKenzie, who leads Church of the Redeemer, an Anglican congregation in Nashville, Tennessee, said he wanted to hate the feature — he views Facebook as willing to exploit anything for money, even people’s faith.

But he thinks it could be encouraging to those willing to use it: “Facebook’s evil motivations might have actually provided a tool that can be for good.”

His chief concern with any Internet technology, he added, is that it can encourage people to stay physically apart even when it is unnecessary.

“You cannot participate fully in the body of Christ online. It’s not possible,” McKenzie said. “But these tools may give people the impression that it’s possible.”

Rabbi Rick Jacobs, president of the Union of Reform Judaism, said he understood why some people would view the initiative skeptically.

“But in the moment we’re in, I don’t know many people who don’t have a big part of their prayer life online,” he said. “We’ve all been using the chat function for something like this — sharing who we are praying for.”

Crossroads Community Church, a nondenominational congregation in Vancouver, Washington, saw the function go live about 10 weeks ago in its Facebook Group, which has roughly 2,500 members.

About 20 to 30 prayer requests are posted each day, eliciting 30 to 40 responses apiece, according to Gabe Moreno, executive pastor of ministries. Each time someone responds, the initial poster gets a notification.

Deniece Flippen, a moderator for the group, turns off the alerts for her posts, knowing that when she checks back she will be greeted with a flood of support.

Flippen said that unlike with in-person group prayer, she doesn’t feel the Holy Spirit or the physical manifestations she calls the “holy goosebumps.” But the virtual experience is fulfilling nonetheless.

“It’s comforting to see that they’re always there for me and we’re always there for each other,” Flippen said.

Members are asked on Fridays to share which requests got answered, and some get shoutouts in the Sunday morning livestreamed services.

Moreno said he knows Facebook is not acting out of purely selfless motivation — it wants more user engagement with the platform. But his church’s approach to it is theologically based, and they are trying to follow Jesus’ example.

“We should go where the people are,” Moreno said. “The people are on Facebook. So we’re going to go there.”

AP video journalist Emily Leshner contributed.