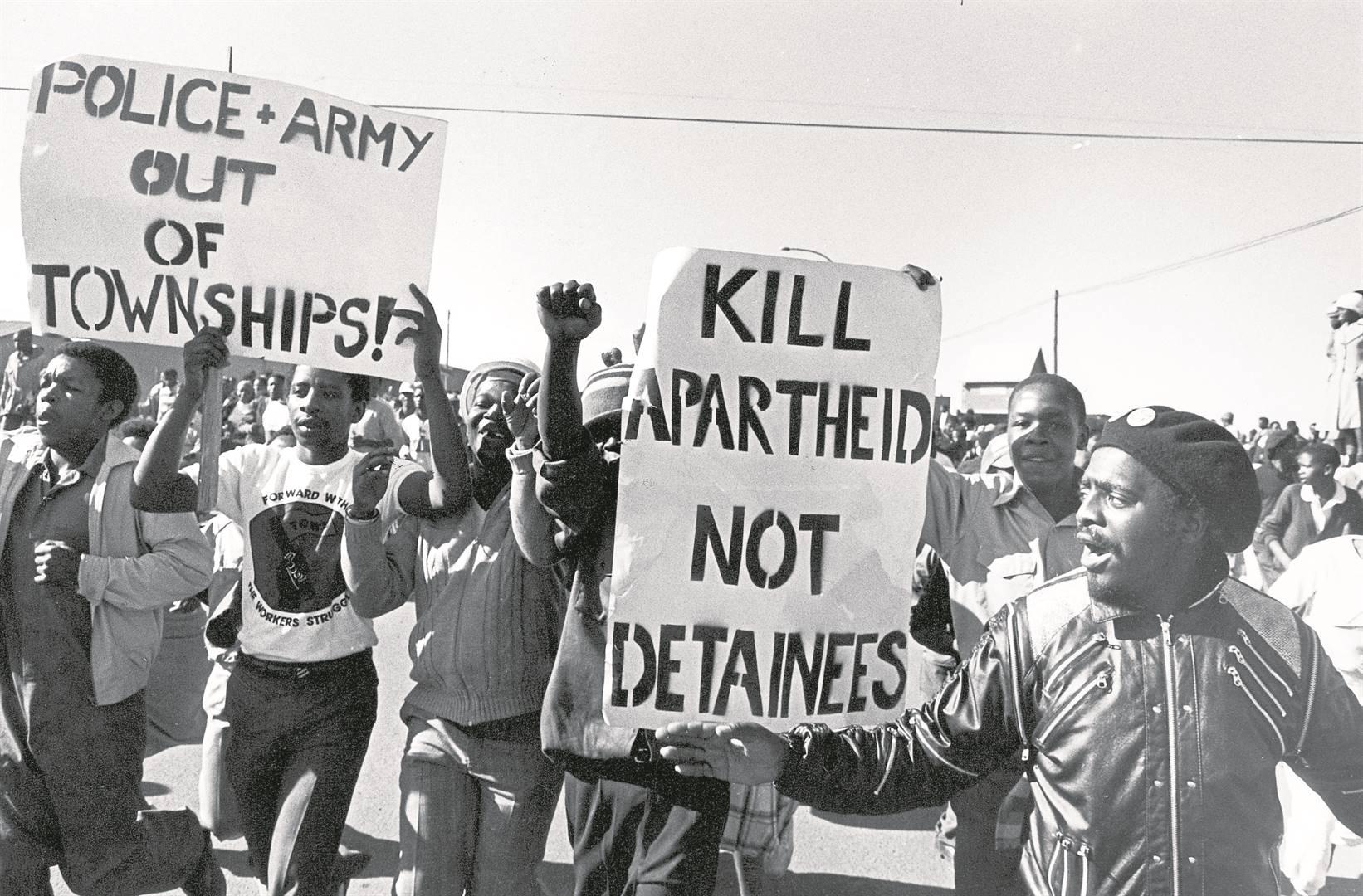

YAOUNDÉ, Cameroon – Twenty-six years after the apartheid system of racial segregation crumbled in South Africa, racism is still an issue that requires a “serious conversation”, according to Catholic bishops in the “Rainbow Nation.”

In a June pastoral letter, the bishops said there is racism not only in society but in the Church, and they challenged Christians to urgently address the problem.

The document challenges the church and South Africans to do everything to overcome racism, the same way St Peter and the early Church overcame through the guidance of the Holy Spirit. The bishops call for addressing social trauma resulting from the violence of centuries of colonialism and the violent decades of apartheid.

“We need to dialogue and work together to achieve healing as a nation. We need to acknowledge the link between race, power and privilege,” they wrote. “We need to redress urgently the economic inequalities present in our society as a result of past racial discriminatory laws and practices; to allay unfounded fears and promote justice.”

The pastoral letter said it is time for the Church to commit itself “to a credible and comprehensive conversation on racism”, and that should translate to the Church asking for forgiveness for “historic complicity with racism in the Church.”

One South African bishop said the initiative is timely.

“There is still a lot of segregation in South Africa,” said Bishop Victor Phalana of the Diocese of Klerksdorp.

“In some schools, including Catholic schools, learners self-segregate, they do not mingle. Indians club together, coloreds club together, blacks club together and whites club together. It is always just a small minority who interact across racial lines,” the bishop told Crux in an exclusive interview.

In South Africa, “colored” is a term used to describe the country’s roughly 3.6 million mixed race individuals. They’re the result of intermarriage among white settlers, African natives, and Asian slaves who were brought to South Africa from the Dutch colonies in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

“There is racism in our schools and universities,” Phalana said. “Some of them use Afrikaans as the medium of instruction to exclude the black learners,” referring to the language of South Africa’s white settlers.

“Some keep their fees astronomically high, to ensure that blacks cannot access them. Our black cricket hero, Makhaya Ntini, has shared his own experiences of racism in sports. He hid his own pain and trauma so that he could be seen as a ‘nice black’. Thanks to ‘Black Lives Matter,’ he has now decided to share with us what he has been through.”

“There are tensions in our churches, both Catholic and Protestant, where a church that is predominantly white finds it difficult to accommodate black worshippers. If they do welcome them, blacks are expected to ‘behave’ and ‘worship as we do here, do not bring your black mentality and your black songs here!’,” Phalana said.

“Some of our churches are good models of integration and multiculturalism. They can be used to teach others the beauty of unity and integration,” he said. “Yet we still have other churches that are still exclusively white. They do not apologize to anyone for that. They are untouchable.”

“Subtle racism can be seen when you book accommodations for holidays, and you are asked to declare your race. If you say, ‘we are black,’ you are told: ‘Sorry we are fully booked.’ Some of these practices have been exposed in the media, the owners make it very clear that they receive only white clients,” Phalana explained.

Calling apartheid a crime against humanity, the bishop said the apartheid system left black people “poor as a result.”

Yet whites who benefitted from the apartheid system have shown little inclination to ask for pardon, he said.

“Many whites do not agree with this. Their idea is, ‘forget apartheid and move on’. They are unaware that reconciliation is impossible without economic redress,” Phalana said.

The bishop said formal apartheid might have ended in 1994, but that did not change the socio-economic privilege of whites or the deprivation that befall black South Africans.

“We realize that we did not deal with the impact of racism of on the society, rooted in almost 400 years of colonial apartheid rule,” Phalana told Crux.

He said the path to forgiveness and reconciliation has been made more difficult because there still are groups in South Africa “supporting and promoting racism.”

“They still indoctrinate their children to hate and to discriminate. Unfortunately, some churches of Calvinistic origins still defend apartheid and racism. They have no plan to mingle, to integrate or to reconcile. They feel that they have lost political power. They carry with them the fear of the black majority, the fear of losing economic power, security and privileges,” Phalana said.

Such churches, he said, “feel they are being swallowed up. Their leaders are telling them to resist change, to refuse any call for unity and reconciliation and that they must instead form exclusive communities with their own security.”

Phalana said such religious leaders often exaggerate demands coming from South Africa’s black majority. He also said the country’s famed “Truth and Reconciliation Commission” has had only limited success.

“It failed because it focused more on ‘truth’ than on the healing of traumatized people,” he said. “Perpetrators, people of privilege, who benefited from apartheid, in most cases did not show repentance, shame and regret. Many victims left the TRC saying, ‘this person has never said ‘sorry’, how can I forgive him?’”

Phalana told Crux the bishops see fighting racism as “a duty and a righteous call,” and noted that the Church is always on the side of those on the receiving end of racism.

“The Church, through its pastoral letters, workshops, seminars and homilies, is trying to expose racism, challenge it and educate people about it so that they can deal with it. We cannot ignore signs and symptoms of racism,” he said.

“We have incidents of ‘hate speech” coming through social media. We are grateful that in some instances, those who were caught, doing hate speech, were prosecuted,” Phalana said.

The bishop also said the affects of apartheid and racism can be “generational.”

“Those born after 1994 are affected by apartheid because their parents still carry the trauma of apartheid and colonialism,” he said. “There are times where people or generations carry the trauma of their ancestors: the anger and prejudices, the fears and anxieties.”

Phalana said that unless the realities of the past are reversed, South Africa cannot move forward. For that to happen, he insisted, there has to be structural transformation, true equality, the redistribution of the land and economic opportunities for the poor and marginalized.

“We need healing. We need to reclaim the “image of God’. If we can see the image and the glory of God in the other person, then there will be no room for racism and xenophobia,” he said.