A Philippine bishop expressed hope for the renewal of a community-centered church under his country’s new leader, Ferdinand Marcos Jr., who has not shaken off his family’s notorious legacy.

“I am sure that most of us, if not all, are already aware of the well-funded, well-orchestrated and systematic whitewashing of the Marcos history,” Bishop Gerardo Alminaza of San Carlos told a virtual forum of more than 100 Philippine- and U.S.- based peace workers.

“And regrettably, we might have to humbly admit that we, particularly as church, may have acted too late in response,” said Bishop Alminaza.

The bishop said, however, “we just have to start creating the circles of forces … that are very much aware of what is happening.”

He told the Aug. 23 forum that the synod on synodality preparation in the Philippines is a “very powerful moment,” as the bishops look more closely at their decision-making and leadership response and how they should be responding to the country’s difficulties by listening to those in the peripheries. He said he is looking to a return to “basic ecclesial communities,” in which church communities of families come together on issues of spirituality and social justice, whether for better formation or to tackle various challenges.

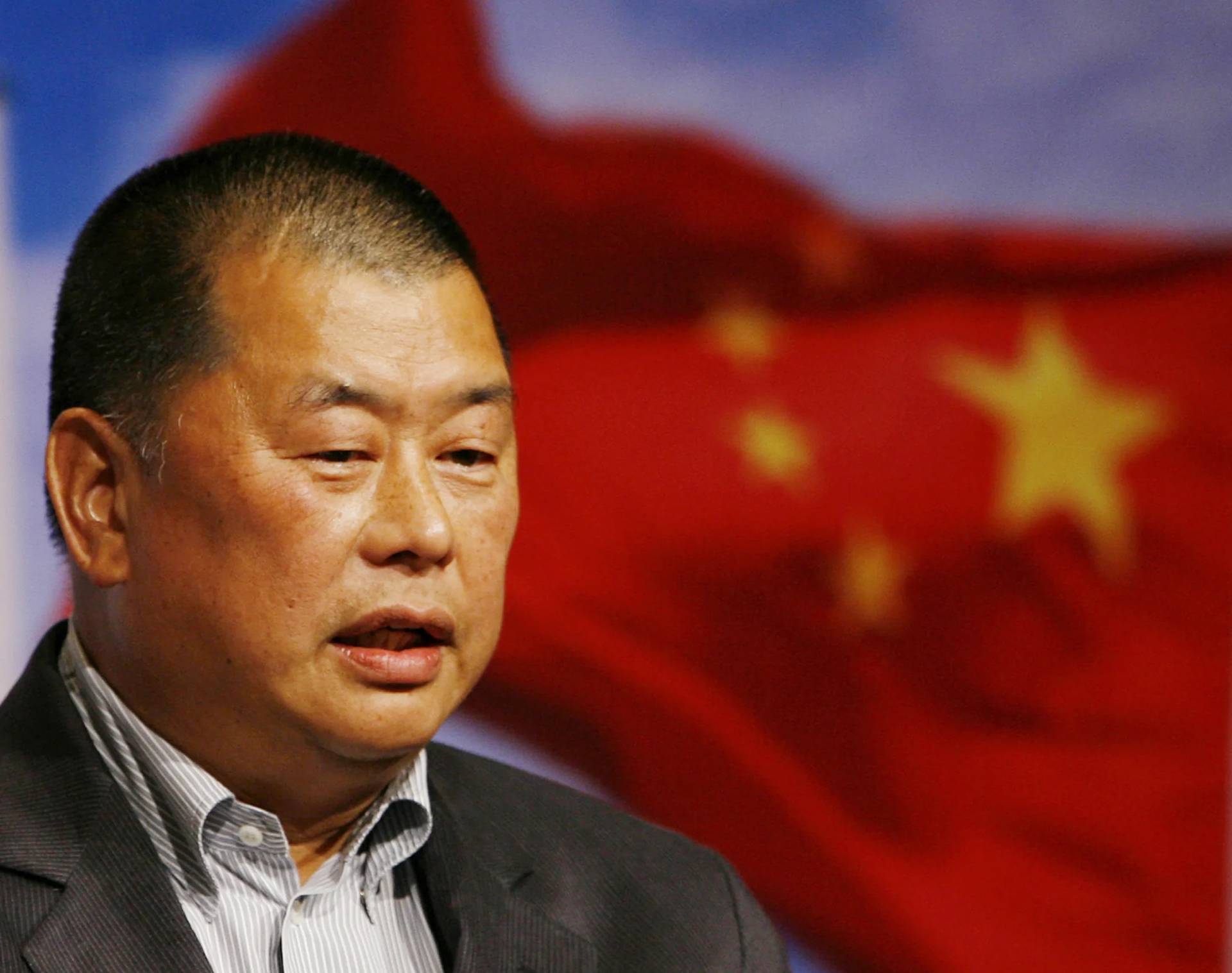

Marcos, a former senator and congressman, took office in June. He is the son of a Philippine dictator who amassed billions through questionable means and whose leadership from the late-’60s to the mid-’80s helped steer the island nation toward its politically and economically unstable status.

Alminaza recently made headlines for speaking out against a new movie about the Marcos family in the last 72 hours before they fled the Philippines to seek asylum in the United States; the movie portrayed the family in a good light.

The forum, hosted by the Maryknoll Office for Global Concerns, the U.S. chapter of the International Coalition of Human Rights in the Philippines and other Christian organizations, was held in preparation for the 50th anniversary of martial law in the Philippines, Sept. 21.

Alminaza, a human rights advocate, grew up in sugar cane country in Negros Occidental province, where there was a famine under the first Marcos. His slide presentation showed a systematic government takeover of the country’s sugar industry.

Investigators found the Marcos administration’s new sugar commission operated all buying and selling of sugar and set a price for planters and millers, who lost an estimated $1 billion in profits, went deep into debt, left close to 200,000 people jobless and shredded Negros Island’s economy. The government sold sugar at low prices to Marcos associates, who then sold it back for significantly higher prices.

Following a bloodless uprising in the Philippines that deposed Marcos in 1986, further investigations found that the sugar commission was just one of multiple fronts to carry out graft across a country rich in resources such as coconuts, bananas, rice and other farmed products.

Students, workers, ordinary citizens and a significant number of clergy and religious rose up in protest, but they faced incarceration and other human rights violations under martial law.

More than 9,000 Filipinos filed a lawsuit against Marcos citing detention, extrajudicial killings, disappearances and torture during those 14 years of martial law. A Hawaii court in 1995 awarded $2 billion in compensation to the victims, but in 2017, the Philippine Court of Appeals overruled the claimants’ demand for payment from the government.

Retired Methodist Bishop Solito Toquero told forum participants about what the country was like under the first Marcos regime.

Toquero spoke of search and seizure orders against his close associates and various clergy, including Catholic priests, who were detained and tortured. He recalled the use of liturgy, music and Scripture passages to protest what was happening, and that various groups mobilized student and farmer protests.

The bishop pointed to centuries-old “feudalism, fascism and neocolonial imperialism” that brought the Philippines to its current state. He said the country would have a difficult road ahead under the new president, but added he still had hope.

“By changing the leader without changing the structure, we have now these political dynasties in our own time,” said Toquero. “We continue to minister to people, we continue to use the Bible in our churches, but there is still repression in the various regimes that followed. We need to be vigilant in our work as church people so the truth will prevail and will finally help us transform the Philippines as the Pearl of the Orient Seas once again.”