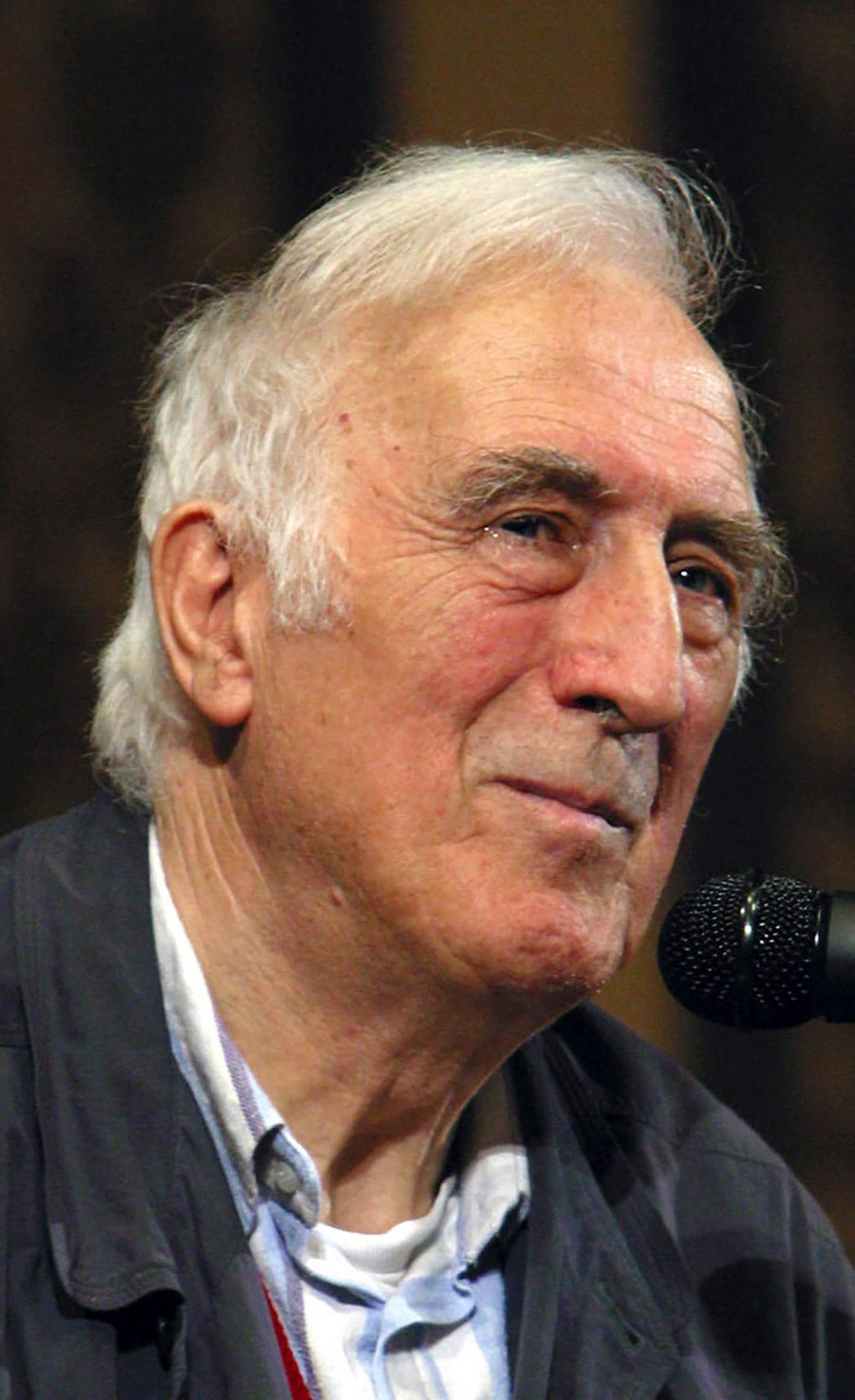

ROME – At nearly a month since his passing, the legacy of Jean Vanier is far from forgotten, and continues to live on in friends and colleagues who say the Canadian theologian not only impacted their lives personally, but also changed theology and the way the Church views the human person.

“He was such a humble man with such a passion for what he did, he was adamant that he was going to do something that would make a difference, and it wasn’t about fame, it was about putting his ministry on the map, and he did that by creating homes for people and vehicles for relation,” Cristina Gangemi told Crux in an interview.

“Do I think Jean Vanier is a saint? I think Jean Vanier is a modern-day prophet,” she said.

Gangemi is co-director of The Kairos Forum and an expert in pastoral care for people with intellectual disabilities. In the past, she has partnered with the Vatican Council for the New Evangelization in organizing and hosting conferences on catechesis for people with disabilities.

She was speaking nearly a month after the May 7 death of Vanier, who lost a battle with cancer at the age of 90, passing away in a Paris facility run by the L’Arche community that he founded in 1964.

Born in 1928 in Geneva to Canadian parents, Vanier eventually abandoned his academic endeavors and, after befriending a French priest, became aware of people suffering from disabilities. In response, he invited a couple of other friends to come live with him and a handful of disabled persons in Trosly-Breuil, France, launching what became the L’Arche movement.

RELATED: With death of Jean Vanier, Catholicism loses a living saint

In 1971, Vanier co-founded the Faith and Light movement, focused on people with learning disabilities. L’Arche has spread to more than 37 countries, and Faith and Light to roughly 80.

After his death, Pope Francis told reporters on board his flight from Skopje, Macedonia to Rome that Vanier was “a man who knew how to read the Christian efficiency of the mystery of death, the cross, of sickness, the mystery of those who are disrespected and discarded by the world.”

“He didn’t just work for the least of us, but also for those who, before being born, there is the possibility of condemning them to death,” he said, calling Vanier “a great witness.”

According to Gangemi, Vanier gave the world an image of humanity “where diversity was our richness.” And the core of this image, she said, was Vanier’s call to follow God “in the fullest love” through the friendships he built.

“I think that what it did was it woke the world up.”

In what could be seen as part of this “waking-up” experience, Vanier’s influence has not only opened the door for thoughtful reflection on those with intellectual disabilities, but his practical legacy continues to ripple through the Church, influencing Catholic minds and inspiring action.

In terms of his practical impact on theology, pioneering what has become known as the “theology of disability,” Gangemi said Vanier “transformed theology, there’s no doubt about that, and nobody else has done what Jean has done. No one.”

Luca Badetti, who holds a PhD in disability studies with background in clinical psychology and theology, hailed Vanier as a model who not only shaped his vision of humanity, but who helped inspired his own career.

Speaking to Crux, Badetti said he first came into contact with L’Arche about 10 years ago in the United States. He joined the movement while living in the Boston area and moved to different communities in Europe, including the house in Trosly-Breuil, where Vanier lived.

After spending several years as part of the L’Arche community and being in daily contact with the disabled, he chose to do his doctorate in disability studies, and has recently published a book based on his experience in community, I Believe in You, with a forward written by Vanier.

Badetti hailed Vanier as a simple and humble man whose “profound and grounded gentleness” stuck out the most.

This was lived out primarily in simple everyday experiences, he said, recalling one night in community when Vanier gathered everyone into a circle to discuss their fears. At another point, Badetti recalled walking down the other side of the street while Vanier was speaking to someone else and, after seeing him, Vanier removed his hat and made a small bow.

“It was such a fun, nice little thing,” Badetti said, explaining that for him, this gesture “really shows that he noticed and he had a respectful demeanor in front of humanity, in front of people,” but especially the marginalized, including those with intellectual disabilities.

“In his vision he emphasized how precious and important they are. I think this has also influenced hopefully the Church, especially toward his later years,” he said, noting that at times there is a danger of treating disabled people “as inferior,” even unintentionally.

“Even if people have the intention of doing good, there can often be a sort of power deferential, like ‘I’m better and I can help you,’” Badetti said, adding that for him, Vanier’s style of community was a “refreshing” way of viewing the disabled as equals.

Similarly, Father Daniel Hess, a priest from Cincinnati working on a doctoral thesis exploring the reception of the Eucharist by people with disabilities, said that although he was already exploring the theology of disability, Vanier has catapulted and deepened his research.

Hess, whose youngest sister has Downs Syndrome, told Crux that he “can’t image life without her,” and believes her presence in his family helped plant the seeds for his vocation to the priesthood.

While in seminary, he wrote a master’s thesis on the possibility of marriage for people with Down Syndrome, and that it was during his research that he encountered Vanier’s 1984 book, Man and Woman He Created Them, which explored human sexuality.

“I discovered that in Christian theology Vanier has a distinct voice and an incredible voice,” Hess said, saying he “devoured” the book, finding it “inspiring and excellent.”

“That was my introduction to Jean Vanier and the theology of disability, and it was inspiring, it was hope-filled and it was beautiful,” Hess said, calling Vanier “a very unique witness to and voice of what it means to live with that daily awareness of daily vulnerability and dependence.”

One of Vanier’s great gifts, he said, is that “he can put words to it…he lives it but with his philosophical and theological background he writes about it and gives testimony to a life that is bigger than living for gain or for advancement…it’s almost an invitation to live in a preternatural way.”

On whether the answer ought to be yes or no for disabled people to receive the sacraments, Hess said theologians have mixed answers, and that while he personally would recommend allowing disabled persons to receive the Eucharist on a case-by-case basis, “We’re walking delicately.”

Although all people can receive baptism, the Latin Code of Canon limits the reception of the other sacraments of initiation, such as confirmation and the Eucharist, to those who have reached the age of reason, meaning they are often not given to severely developmentally challenged adults. (In the Eastern rite Church, all three sacraments are given to infants, so it is less of an issue.)

Either way, they should be a part of the regular parish community, including during the liturgy, he said, adding that for him, the takeaway from Vanier is that if a community “doesn’t include people with disabilities, and serious disabilities, it doesn’t really reflect the Church, the body of Christ, fully.”

Hess said his current research is based largely on Vanier and Thomas Aquinas, as well as other modern theologians beginning to wade into the topic of disability, including Miguel Romero, who attended a Rome conference on disability in 2017 titled, “Catechesis and Persons with Disabilities: A Necessary Engagement in the Daily Pastoral Life of the Church,” which Gangemi helped to organize.

Monsignor Francesco Spinelli, who works in the Vatican Congregation for the New Evangelization and who played a leading role in organizing the event, told Crux that “Jean Vanier’s legacy in the Church is great, in his works, but even more so in his witness of life and in the fruits that this has made sprout for the Church and for everyone.”

“In a world that is increasingly more selective and individualistic, shy and almost fearful of human contact, the words Jean Vanier often repeated come strongly to mind: We human beings are not made to show strength, greatness or power; we humans are made for encounter. Encounter as an end in itself.”

Vanier’s life, he said, “can be synthesized with one word: encounter.”

According to Spinelli, there is an increasing interest in the theology of disability – an observation Gangemi, Badetti and Hess all echoed.

Spinelli said that in his experience organizing the 2017 conference, which produced guidelines for catechesis for disabled people and their participation in the liturgy, there was “great enthusiasm” for the topic in the Church throughout the world.

In terms of what future theology of disability might have in the Church, he said he believes it will be based on seeing the disabled not as people who are “sick,” but who “are subjects of pastoral care and catechesis.”

“It is important above all to start from the idea that people with disabilities are indeed objects of catechesis, but they are and must also become subjects,” he said, recalling how Francis during his speech to attendees of the 2017 conference voiced hope that disabled people would increasingly lead catechesis, transmitting the faith “even with their testimony.”

“People with disabilities, in their own way, have a desire for God, their faith and their own spirituality,” Spinelli said, adding that this is the same for people who are not disabled, each of whom have a different and personal relationship with God.

For Gangemi, she said she would like to build on Vanier’s writings by expanding his focus on vulnerability, exploring weakness, specifically the challenges of the disabled, as a source of strength.

With many already hailing Vanier as a saint, Gangemi said she agrees, and thinks he is someone “people should continue to look up to.”

Similarly, Badetti recalled how in one interview, Vanier was asked about being a saint, and replied that the most important thing in life “is to be a little friend of Jesus. So, I hope that he’s praying for us and that he’s close to us as a little friend of Jesus.”

Follow Elise Harris on Twitter: @eharris_it

Crux is dedicated to smart, wired and independent reporting on the Vatican and worldwide Catholic Church. That kind of reporting doesn’t come cheap, and we need your support. You can help Crux by giving a small amount monthly, or with a onetime gift. Please remember, Crux is a for-profit organization, so contributions are not tax-deductible.