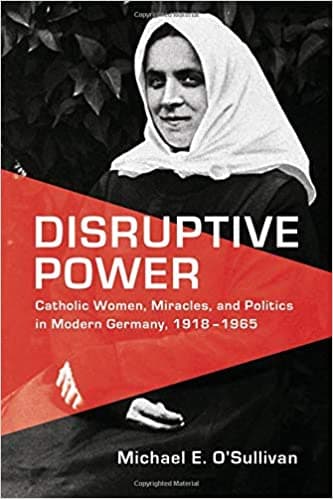

NEW YORK — In his book, Disruptive Power: Catholic Women, Miracles, and Politics in Modern Germany, 1918-1965, Marist College professor Michael O’Sullivan explores the revival of Catholic faith in Germany from 1920-1960, fueled in large part by Marian devotion.

Yet ironically, this new sense of devotion, primarily from traditionalist Catholics, unintentionally weakened the institutional Church, O’Sullivan argues.

His book, which won the Waterloo Centre for German Studies Book Prize, explores this turbulent period in German Catholicism, and in an interview with Crux, O’Sullivan offers his thoughts on what it means for one of the most influential Catholic nations in the world today.

Crux: These miracles you chronicle — often occuring in very rural areas — take place when Germany is in tremendous upheaval after the first World War. Are the devotions you chronicled here more politicized than say previous well known Marian devotions, such as, say, Lourdes?

O’Sullivan: I have trouble thinking of an era in European history where popular religion and sainthood was not politicized. In an example from the medieval period, my colleague at Marist College, Janine Larmon Peterson, just wrote a book that shows how the political situation on the Italian peninsula during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries shaped the reception of local and unsanctioned saints’ cults.

In modern European history, the Lourdes apparitions were in fact quite political. Although the history of Bernadette Soubirous is certainly a local story about how formal rituals of the Church mixed with local traditions, the shrine became a lightning rod of controversy in the political battle between secular republicans and conservative Catholics during the late nineteenth century. I would also point out David Blackbourn’s study of the Marpingen apparitions of the Virgin Mary that highlighted the political clash between the Catholic minority and Protestant elites in Prussia during Germany’s Kulturkampf (cultural struggle) of the 1870s.

While my book is not the first to demonstrate that unsanctioned religious figures became ensnared in politics, it follows how faith in religious miracles encountered new political terrain during the twentieth century. Of most interest is how Therese Neumann of Konnersreuth and other mystics fit into Catholic attempts at liberal democratic mass politics during the 1920s and 1950s. Furthermore, her circle’s messy engagement with the Third Reich’s dictatorship highlights many of the grey areas in the relationship between Catholicism and fascism. Many of her followers suffered imprisonment or death during this era, but I argue that she backed away from open acts of dissent against National Socialism.

Conservative Catholics would be characterized today as those wanting to preserve the institutional Church and its traditions, but you write that during this time, traditionalist believers unintentionally weakened it. How so?

This is perhaps the most provocative element of my book’s argument and it relies on the work of other scholars, such as Thomas Grossbölting, who show that institutionalized Christianity in Germany faded in the 1960s and 1970s. Although church attendance and membership declined, many Germans and other Europeans developed personalized beliefs outside the structures of churches that mixed different faith traditions.

Catholics attracted to unsanctioned instances of stigmata and apparitions of the Virgin Mary understood themselves to be more traditionalist in their faith practices than even some of the bishops, the clergy and leading members of the laity, whom they viewed as making too many compromises with modernity. However, they believed so strongly in their own traditionalist vision that they rebelled vigorously against the authority of the Church’s hierarchy and contributed to an erosion of institutional legitimacy. By demanding a personal connection with God that eliminated priests and hierarchical sanction as intermediaries, mystics and seers contributed to the larger pluralization and individualization of religion that overtook Germany in the period that followed them. I never claim that the hundreds of thousands of pilgrims to small rural towns were exclusively responsible for this broader shift in spiritual practices. Long-term shifts toward urban lifestyles, consumer economies, socialism, totalitarianism, and war all contributed. Nonetheless, the traditionalist rebels who valued unsanctioned mysticism over Church hierarchy accelerated these larger trends in surprising ways.

How did the story of Therese Neumann’s stigmata first catch your attention? As you chronicle, she caught the attention of hundreds of thousands of Germans and other European Catholics and even folks in the United States. You suggest that some of the cult that developed around her was fueled by the belief that Catholics in Germany had compromised too much with the modern nation state and were no longer living authentic Catholic lives. Can you explain this a bit more?

I first became interested in the veneration of religious seers such as Neumann by accident. When researching a dissertation largely about the secularization process of the Catholic regions of Germany, I discovered folders about alleged cases of stigmata and Marian appearances in the archive of the archbishopric of Cologne. Although I set these sources aside for many years, I eventually realized that there was a compelling book that could emerge about the resonance of Catholic mysticism in Germany from the 1920s to the 1950s. The challenge of the study was to find deeper meaning out of microhistories that had such colorful personalities and narratives.

The struggle by the German Catholic minority to fit into the Protestant-majority nation-state founded in 1871 became one of these touchpoints. After a traumatizing church-state battle during the 1870s, German Catholics made efforts to reach out from the subcultures created by the legacy of the Reformation to both demonstrate their loyalty to the new nation and integrate into the modern, urban economy. This led many bishops, clergy, and lay leaders to balance a sense of rationalism with their faith. It also caused the political party that represented Catholics (the Center Party) to overcome past differences and govern with secular opponents, such as the liberal and social democratic parties. Those most attracted to instances of stigmata in the 1920s rejected modernization of the faith or political Catholicism as inauthentic. Sites such as the home of Therese Neumann in rural Konnersreuth became symbols of opposition against the perceived abandonment of the faith by clergy from industrialized northwest of the country; bishops who deployed scientific methods to analyze the authenticity of alleged miracles; and Catholic politicians who dared compromise with past enemies of the Church.

How much momentum does the cause for her beatification have today and who are the major players in it?

My sense is that the momentum for beatification slowed in recent years, but I have also found it difficult to gather much information about what is happening beneath the surface. Perhaps I could have used some of your journalistic skills here. This year marks the fifteenth anniversary of when Gerhard Ludwig Müller started the process as Bishop of Regensburg and no report has yet been submitted to the diocese with an assessment of Neumann’s heroic virtue or forwarded to the Vatican. I did interview the two figures leading the process in 2013: Msgr. Georg Schwager, who will send a report to the Bishop of Regensburg once all research is complete; and Toni Siegert, a journalist and historian based in Munich who leads an historical commission. In their comments to me and in subsequent public statements, they emphasize the vast amount of documentation that must be surveyed before a report is finalized. In a recent appearance in Konnersreuth, Siegert publicly stated that new documents have been released to the commission from the personal papers of Neumann supporter Fritz Gerlich, whose own beatification process started in 2017, and also from a religious order with links to Neumann.

Despite denials by both Schwager and Siegert, I speculate that the divisions within the Catholic Church between progressives and conservatives must play a role in the prospects of this beatification case. Cardinal Müller, who started the process right after Benedict XVI assumed the papacy, served as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith after his time in the Regensburg bishops’ residence and now appears regularly in the press as an aggressive critic of Pope Francis. He also recently compared the Synodal Path adopted by the German Bishops to address a movement for women’s empowerment within the Church and the sex abuse scandals (which Müller played a part in covering up) to Hitler’s consolidation of power in 1933.

While the current Bishop of Regensburg, Rudolf Voderholzer, seems publicly supportive of Konnersreuth, the recent association of the town and other sites analyzed in my book with deeply conservative Catholicism and right-wing populism, would seem to make it unpalatable to the current pontiff and most German Catholics who live outside the diocese of Regensburg. In some ways, the present conflict among Catholics in Germany has dimensions that were similar to the divisions within its Catholic community during the Weimar Republic of the 1920s.

How did individuals such as Neumann change the way the German hierarchy related to women in the 20th century and the movement by other women in the Church seeking an expanded role in leadership?

The book treats the history of women in the Catholic Church extensively, but it largely explores the exceptional nature of Therese Neumann’s accumulation of power as a seer in modern Catholic history. Disruptive Power argues against studies that view female stigmatics and visionaries as popular theologians who used mysticism to pursue a form of Catholic feminism. It also questions scholars that depict religious women as manipulated pawns in the hands of their religious patriarchs. Rather, the book highlights the story of a woman who adopted deeply conservative and traditionalist positions as she increased her fame and agency over time. Most other girls and women in her position suffered terribly as a result of claiming a direct connection to sacred figures. If they submitted too much to patriarchal authority or rebelled too aggressively against it, they wound up ruined, discredited and sometimes excommunicated. Many of them were institutionalized. Neumann carefully navigated a path where she cultivated male patrons to protect her without empowering any one of them too much. She used loyalty to her father in order to shield herself from her bishop’s desire for her institutionalization. Neumann also instrumentalized the Church’s conservative sexual politics as a tool with which to wield moral authority.

Neumann’s approach to gender did not influence the German women leading the Maria 2.0 movement that calls for feminine empowerment within the Church in Germany today. Their predecessors were active within the Catholic Women’s Movement of the early twentieth century, a subject for my new book project. Nonetheless, it is vital for scholars of women’s history to access the mindset of traditionalists such as Neumann and the many women devoted to her during the era of the two world wars.

Follow Christopher White on Twitter: @cwwhite212