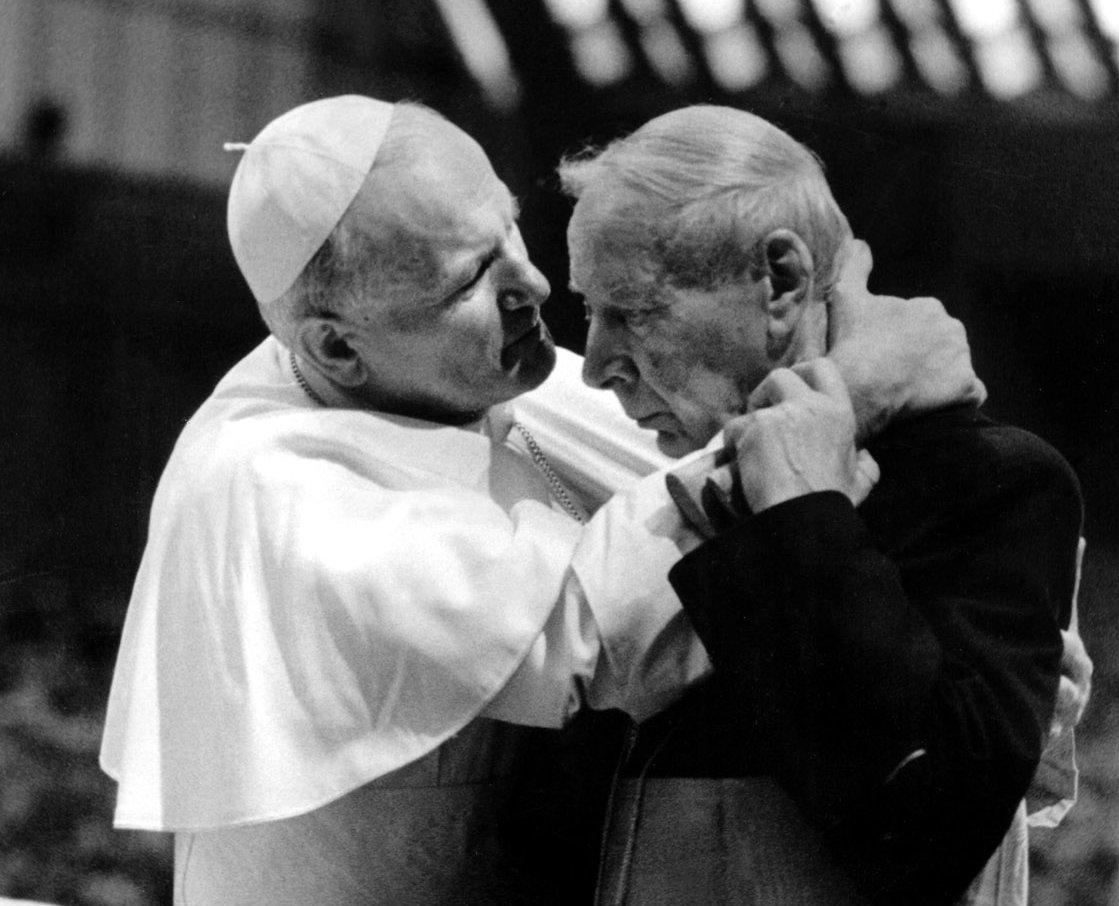

KRAKÓW, Poland – When he became pope, St. John Paul II said, “There would be no Polish Pope without the Primate.”

The primate he referred to was Polish Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński, who will be beatified September 12.

Wyszyński, the “Iron Primate” known for his resistance to communism, was born in Zuzela, 75 miles east of Warsaw, on August 3, 1901, when Poland was still dived between Russia, Germany and Austria after the late 18th century partitions of the previously independent country.

He was only 9 when he lost his mother, Julianna. When his mother was dying and a teacher told him to stay after in class – teachers were sent by the Russians in his region – little Stefan said he didn’t want to go to a school like that and rushed home to say goodbye to his beloved mother.

“It was an early sign of his steadfast bravery,” writes Ewa Czaczkowska, author of a 1000-page biography of Wyszyński.

Julianna passed away the same day: “I transferred all my love from a Mother to a Mother,” Wyszyński wrote years later in his book Pro Memoria, referring to Virgin Mary who he credited with guiding and protecting him through the years of communist oppression.

He gambled everything on Mary

In February 1953, six months before Wyszyński’s arrest by the communist regime, the Primate said, “I gambled everything on Mary.”

The story is recounted in Czaczkowska’s book, Primate Wyszyński. Faith, Hope, Love. The author noted John Paul II spoke about the relationship of Wyszyński with the Blessed Mother: “He found spiritual freedom in the absolute devotion to Virgin Mary. Yes, he was a free man, and he was teaching us, the Poles, true freedom.”

Wyszyński was a martyr of the communist era – he was already the Primate of Poland when he was imprisoned for three years by the regime, kept in three different locations. He was constantly spied on and kept in dire conditions, which in harsh winters of eastern Poland at the time made his health deteriorate badly.

“He never complained, and never said a bad word about his opressors,” writes Czaczkowska. “On the contrary – he prayed every day for Bolesław Bierut,” the then-president of Poland.

Wyszyński recalled that a day after Bierut’s death in 1956, the late president came to him in a dream, which made Wyszyński pray for Bierut’s soul passionately.

The cardinal’s episcopal motto was “Soli Deo” – “Only God” – to which he added through the years “per Mariam” – “through Mary.”

Czaczkowska writes the cardinal made a spiritual home of Jasna Góra, the sanctuary of Black Madonna of Częstochowa, and visited it 136 times during his life.

Wyszyński was known for always having time for people, saying, “time is love.”

Once, Czaczkowska writes, he negotiated with Władysław Gomułka, the leader of the Communist Party of Poland, for 11 hours to achieve some freedom for the Church.

“It was a love for the brother who was leading Wyszyński to fight for the right to proclaim the faith in communist Poland, the regime that wanted to take that human right away from the people,” the author continues.

The Communist Party wanted to supplant Wyszyński with a younger cardinal – Karol Wojtyła, the future Pope John Paul II. But Wojtyła decided to live in the shadow of the Primate: When the primate was once refused a passport by the regime and therefore couldn’t go to Rome, Wojtyła said he wouldn’t go either.

When French President Charles De Gaulle came to visit Poland in 1967 and the regime refused him a meeting with the Primate, Wojtyła said he would not see the French leader at the Wawel cathedral. When he was pope, John Paul recalled that he did not want to offend the Frenchman – he just couldn’t do what the Primate was not allowed to do.

Putting women at the center of the Church

Wojtyła was close to the primate, even vacationing with him on occasion. He was devoted to the elder statesman of the Polish Church.

When he was pope, John Paul credited Wyszyński with making a policy of having more women in positions of influence in the Church.

Wyszyński’s closest collaborator was Maria Okońska, a founder of “Ósemka” – “The Eight” – a group of lay women officially called “The Lay Institute of Helpers of Mary of Jasna Góra,” which changed its name to “The Institute of Primate Wyszyński” after the cardinal’s death in 1981.

Okońska was Wyszyński’s personal secretary and adviser. She also recorded and transcribed every one of the cardinal’s homilies, which today is a valuable historical resource. She also took hundreds of photograph’s of the Primate, which continue to feature in museum exhibitions and on book covers.

When the Primate was arrested, Okońska and the women of the institute mobilized millions of Poles to pray for the Primate’s freedom.

She was the one who helped draft one of the grandest projects of Wyszyński – a millennial program of prayers that led to the 1966 celebrations marking 1000 years of Christianity in Poland, a commemoration opposed by the regime.

In Pro Memoria, Wyszyński wrote: “People were often amazed what this group of young women is doing around the Primate. Some are concluding it in their own way. And this is, after all, very simple. Those women are interpreting – in all dimensions – Motherhood for me. Each and every one of them reminds me about some aspect of the image of a Mother.”

Follow Paulina Guzik on Twitter: @Guzik_Paulina