[Editor’s Note: This is the second in a series of articles by Inés San Martín exploring the state of the Catholic Church on Pope Francis’ home continent of Latin America. The first article can be found here.]

ROSARIO, Argentina – The northern Argentine city of Ingeniero Juarez, in the province of Formosa, is known for being hot and dusty. For decades, it has also been considered rife with political corruption, its leaders taking advantage of a largely illiterate population, and the fact that there is a large indigenous population who don’t speak Spanish.

Governor Gildo Insfran, of the Peronist Justicialista party, has been in charge since 1996. The provincial government came under fire over human rights violations committed during the COVID-19 health emergency.

The alleged abuses have been documented in a Human Rights Watch report, which exposed the northern province’s practice of placing suspected COVID-positive patients in mandatory isolation in overcrowded quarantine centers.

The United Nations carried out its own investigation of what happened in Formosa, and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights issued a resolution regarding the health of seven pregnant indigenous women from the Wichi community, who said they had gone into hiding amid fears they would be separated from their babies after they were born under the province’s COVID-19 protocols.

The mishandling of the pandemic is just the latest example of decades of mismanagement and corruption in Formosa.

The province is poor, and over 50 percent of the population didn’t complete primary school, leaving a large number of people illiterate. In addition, the province has a large presence of indigenous populations, particularly the Toba, Pilagá, and Wichí peoples, many of whom don’t speak Spanish.

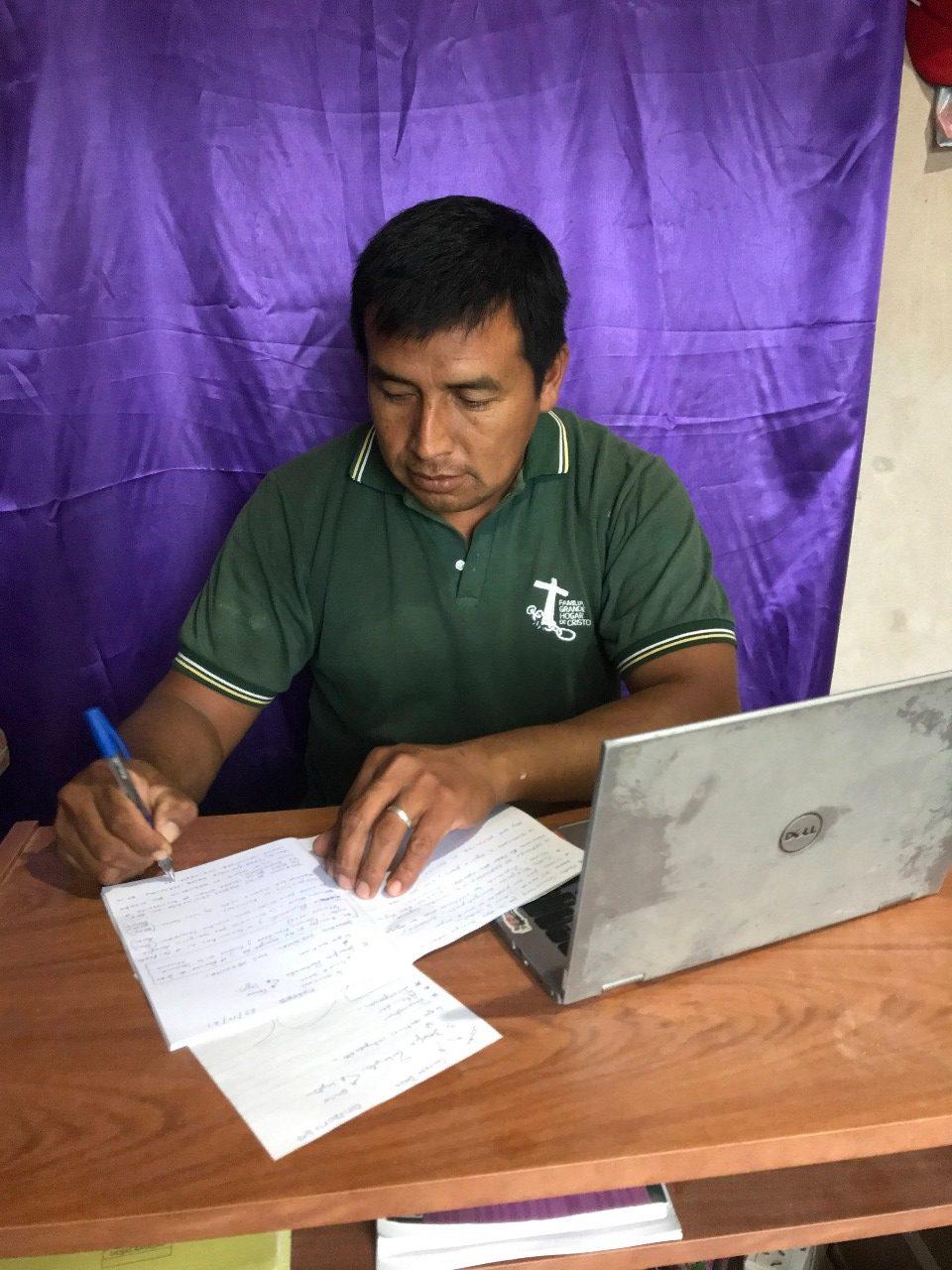

For the past four years, Raul Toribio has been coordinating the Monsignor Enrique Angelelli Center, part of the Familia Grande Hogar de Cristo, a national Catholic confederation of 200 centers helping people fighting drug addiction and the resulting health issues, poverty, homelessness, and unemployment.

Last November, Toribio, an Anglican, was tapped to be the representative of the network at the first Latin American Ecclesial Assembly, a week-long gathering that took place both online and in presence, in Mexico City.

RELATED: Pope Francis calls for ‘prayer and dialogue’ as Latin American Ecclesial Assembly opens

“When they asked me from Buenos Aires if I wanted to take part, I said yes, but I immediately realized that there was much reading I had to get caught up with, beginning with the document of the general assembly in Aparecida from 2007,” Toribio told Crux.

He was referring to the V General Conference of the Episcopate of Latin America and the Caribbean (CELAM) which took place in Brazil.

Toribio didn’t fully grasp what he had said yes to until the pre-assembly that brought together the over 90 delegates from Argentina. He is a member of the Wichi indigenous group. He said after the meeting he became trilingual: knowing his native Wichi, Spanish, and “well versed in all terms Catholic.”

“There were a lot of technical, specific things I had to get caught up with, concepts of the Aparecida assembly, as well as the previous ones… Who knew that Medellin was something other than a city in Colombia? But Juani was very supportive,” he said.

“Juani” is Passionist Father Juan Ignacio Rosasco, who arrived in Ingeniero Juarez seven years ago, and hired Toribio to head the Hogar de Cristo. His congregation has been in the city for 50 years, as a direct response to the 1968 CELAM conference in Medellin.

“I asked him and the people who run the Hogares family in Buenos Aires why they had chosen me, and not perhaps a Catholic, but they all just smiled and said I was the right person for the task,” Toribio said.

Speaking with Crux, Ronsaco explained why they chose Toribio to represent the Hogares in the Ecclesial Assembly: While there was an ecumenical dimension to the choice, most importantly they saw a need to have Argentina’s indigenous population represented.

The Angelelli center in Formosa was the first Hogar de Cristo to work with the indigenous populations.

“It is very difficult for Argentines to recognize that there are indigenous people in this land: The myth that Argentina was born on ships, that we are Europeans who come from outside, is very much ingrained, because it is the reality of the central, richest part of the country,” the priest said. “Argentina annihilated many of its indigenous ethnic groups, and it struggles to come to terms both with this, and with the fact that they are still present,” both in the north and the south.

Ronsaco also pointed out that despite the myth of all Argentines having Italian or Spanish roots from big immigration waves in the late 19th and early 20 centuries, and as such, is Catholic at least by tradition, this is not fully accurate: In the country’s north, most indigenous populations are actually Anglican. This is due to the fact that in the early 1900s, the British owned the region’s tobacco and sugar plantations, and they hired Anglican missionaries to take care of the spiritual needs of the workers.

“When the Anglican missionaries arrived, they saw that most of the workers were indigenous, who spoke another language,” he said. “A few years later, when the heads of the plantations moved on, the missionaries followed the indigenous people and founded many missions in the area, such as the Santa Teresa Mission, the San Pedro Mission, and many others.”

For this reason, the priest said, all the Wichi Indians who go to the center are Anglican, and half of those who work in the center are Catholics, because they are “Criollos” and the other half, Anglican. Criollo is a term used originally to describe people of Spanish descent born in the colonies, but in Formosa is used to refer to anyone who is not indigenous.

All are welcome

Hogar de Cristo has a motto: No one is left over, and all can contribute.

Toribio said that from the beginning, all the conversations he had, both with Ronsaco when they first met and in the Ecclesial Assembly, “centered on what we want to achieve.”

“Yes, we talk about Christ, since he’s obviously at the center, but we don’t talk about one Church or the other, being a priest or a pastor,” Toribio said. “What matters is the fact that we want to help, that Christ is who inspires us, as well as the suffering we perceive in those trapped by drugs and alcohol. It’s ecumenism in action.”

He is convinced that every person can work to help others, and that there are no excuses for not trying to make a difference.

“Many times, we want to turn away to the side, as if saying ‘that is not my problem, it does not concern me’,” Toribio said.

“But as Christians, we are called to evangelize and also to help our neighbor, who might have material needs, yes, but sometimes, they just need a shoulder to lean on, a smile or help with learning to read,” he said.

“In Formosa, it can be hard to work on this, because every soup kitchen, shelter or home for those in the outskirts have to come with the support and green light of the governor, who is omnipresent, even when he’s not there, politics is in the air” he added. “But we persevered, and when the people realized we were here, trying to help but not trying to get elected, they understood what we were about, and came to us.”

Follow Inés San Martín on Twitter: @inesanma