SÃO PAULO – Brazilian Catholics had mixed reactions to the announcement by Archbishop Fernando Saburido of Olinda and Recife that the beatification cause of Archbishop Hélder Câmara (1909-1999) is progressing.

Saburido said on Nov. 15 that the Holy See issued a decree of “juridical validity” concerning the diocesan inquiry on Câmara’s life. The process was launched in 2015 and involved a three-year investigation in which experts collected and analyzed documents and witness statements about the late archbishop.

According to Capuchin Father Jociel Gomes, who is the vice-postulator of the cause, a Vatican-appointed official will now create a biographical study and send it to a number of commissions at the Holy See.

“After that, the pontiff may declare him venerable. But we do not know how long that process can take. Câmara was a very famous man and there is a great number of documents about him,” Gomes told Crux.

While many churchgoers in Pernambuco State and elsewhere – especially the ones who knew Câmara – celebrated the fact that his cause is advancing, several critics have opposed the possible sainthood for a man called the “red archbishop” – a moniker given to him by conservative groups due to his progressive political views.

A highly influential Catholic leader in Brazil and Latin America in the 20th century, Câmara was involved in the pastoral work with the poor since his days as a priest. In the beginning, however, he was not considered politically progressive. For several years, he was an organizer of the Brazilian Integralist Action (AIB), a rightwing movement.

He later distanced himself from the Integralist ideology and was inspired by thinkers like Jacques Maritain, a mid-20th century French philosopher. The leadership skills he showed during his years with the AIB, however, only grew over the years.

In 1952, he was ordained a bishop in Rio de Janeiro. The same year, he was authorized by the Vatican to create the National Conference of Bishops of Brazil (CNBB). He was also a founding member of the Episcopal Conference of Latin America (CELAM).

As a delegate to the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), he was the major proponent of the so-called Pact of the Catacombs, a manifesto of 40 clergy members (many of them from Latin America) in which they vowed to live simple lives, abandoning all signs of wealth, and to put the poorest in society at the center of their ministry.

The Pact was later signed by hundreds of bishops and priests and greatly influenced the Liberation Theology movement.

Between 1964 and 1985, Câmara was the Archbishop of Olinda and Recife, coinciding with the period of the military dictatorship in Brazil. A great advocate of human rights and a critic of repression and totalitarianism, Câmara was continually persecuted by the regime.

Newspapers were not allowed by the government to interview him – in fact, they were forbidden to even mention his name. His personal assistant, Father Antônio Henrique Pereira, was killed in 1969, allegedly by government agents as retaliation for Câmara’s activism. Pereira’s family was visited a few days after his killing by officers of the dictatorship who offered to pay them if they agreed to receive and publicize documents that could unfairly incriminate Câmara.

“He never ceased to work for the poor, even in those terrible conditions. He was the voice of the voiceless and promoted peace during his entire life,” Gomes said.

Câmara was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize on different occasions, but the Brazilian dictatorship pushed to prevent it.

In his archdiocese, Câmara promoted the formation of base ecclesial communities (CEBs), groups made of lay people who gathered every week to read the Bible and discuss their community’s problems under the light of the gospel. The CEBs movement has been strongly influenced by Liberation Theology.

From a socioeconomic point of view, Câmara said poor countries like Brazil needed to adopt policies focusing on their development. He would ask for international cooperation to develop disadvantaged nations on several occasions during international forums.

Traditionalist Catholic movements like the Brazilian Society for the Defense of Tradition, Family and Property (TFP) have been calling Câmara a “red archbishop” since the 1960s, when he pushed for the People’s Republic of China to replace the Taiwan-based Republic of China at the United Nations and advocated for Cuba to be allowed in the Organization of American States.

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, TFP’s founder, said in an article published in 1969 that Câmara’s rhetoric “outline a whole policy of surrendering the world, and more particularly America, to communism.”

Indeed, the Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira Institute (IPCO) was “perplexed” to learn of the progress of his beatification process, said spokesman Frederico Viotti.

“He was notorious for his stances that favored communism not only in Brazil but also in several other countries with the expansion of the so-called Liberation Theology, which he promoted,” he told Crux.

Viotti said many Catholics “know that his personal stances were at odds with the magisterium of the Church and end up getting confused with the beatification process.”

“We hope that it will be suspended. It is a proof, for such Catholics, that there is a crisis in the Church,” Viotti added.

The political polarization in Brazil since the presidential campaign, when former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and incumbent Jair Bolsonaro fiercely contested the race, further intensified the reactions to Câmara’s potential sainthood.

Many of Bolsonaro supporters have taken to social media to accuse Câmara of not being a real Catholic, given that he was a “communist.”

“I understand that those opinions are something positive. Saints are not always unanimously accepted,” Gomes said.

He called Câmara a “true disciple of Christ,” something that can provoke discomfort in many people.

“He may have disturbed some by living an incarnated Gospel among the poor,” he said.

The strong reactions of some of these groups will be collected and analyzed along the process, Gomes said.

“That is why our work must be transparent. We are not allowed to emit any decision. It is up to the Church to give the final word on his canonization,” he explained.

On the other side, many people who have met Câmara believe he is already a saint. That is the case of João Virgílio Tagliavini, an Education professor at the São Carlos Federal University, in São Paulo State.

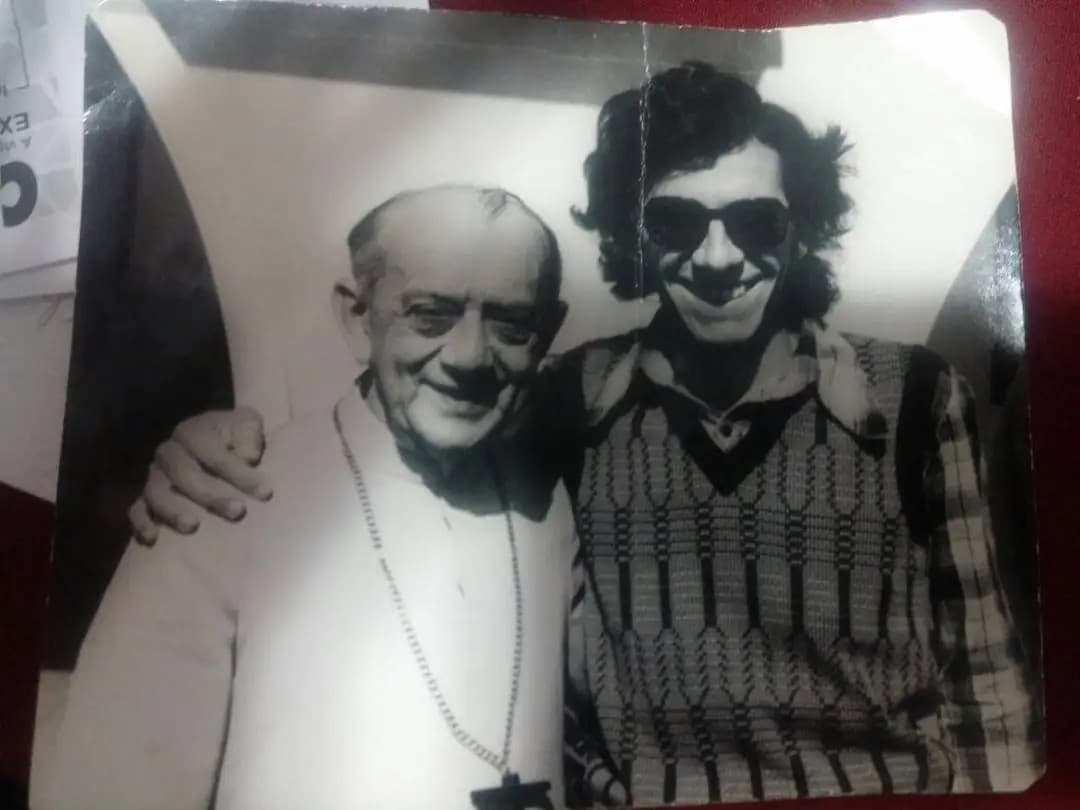

“I studied theology in the 1970s and was a priest for eight years. On two occasions, he came to our seminary in order to minister conferences and direct spiritual retreats,” he told Crux.

Tagliavini recalled one morning Câmara disappeared and left everybody worried. Hours later he arrived in a bus and told the people that he walked to a distant district in order to visit a Catholic bookstore.

“People asked him why he went by foot, and he answered: ‘I need to see the people, talk to the people.’ The shop clerk had to give him some money so he could pay for the bus ticket and come back to the seminary,” Tagliavini said.

He never forgot how Câmara was moved and cried during Eucharist.

“He had a great love for the Eucharist. He would wake up at 4 a.m. to meditate and pray before feeling prepared to celebrate the Mass at 6 a.m.,” he said.

Tagliavini says the same smear campaign that Câmara suffered during his life is now happening again.

“He had a famous phrase about it. ‘When I give bread to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask questions about the causes of poverty, they call me a communist,” he said.

In the opinion of Gomes, “many of his critics did not know him or his work.”

“Many people manifest their opinions based in things they heard from other people. They need to learn more about Archbishop Hélder Câmara,” he said.