PAULO – A growning number of priest suicides in the world’s largest Catholic country has left Brazilian clergy taking a hard look at the causes of suffering in ecclesial life, with some suggesting synodality may offer an antidote.

According to Father Lício de Araújo Vale, an expert in suicide among clergy members with decades of research on the topic, between August 2016 and June 2023, 40 priests committed suicide in Brazil.

Given that the country overall has a relatively low suicide rate by global standards at 5.7 per 100,000 inhabitants, according to the medical journal The Lancet, one would expect roughly 1.7 suicides among Brazil’s 30,000 priests each year, or around twelve over a seven-year span.

Forty, therefore, represents a priest suicide rate almost four times higher than the national average.

And the number keeps growing. On Nov. 18 alone, two priests, ages 34 and 45, killed themselves, as well as a former priest.

“Among so many issues, that problem appears as a major concern for us. Most of us knew a brother who appeared to be fine and suddenly took his own life,” said Father Geraldino Rodrigues de Proença, a member of the group “Priests of the Path,” which gathers dozens of progressive clergy members all over Brazil.

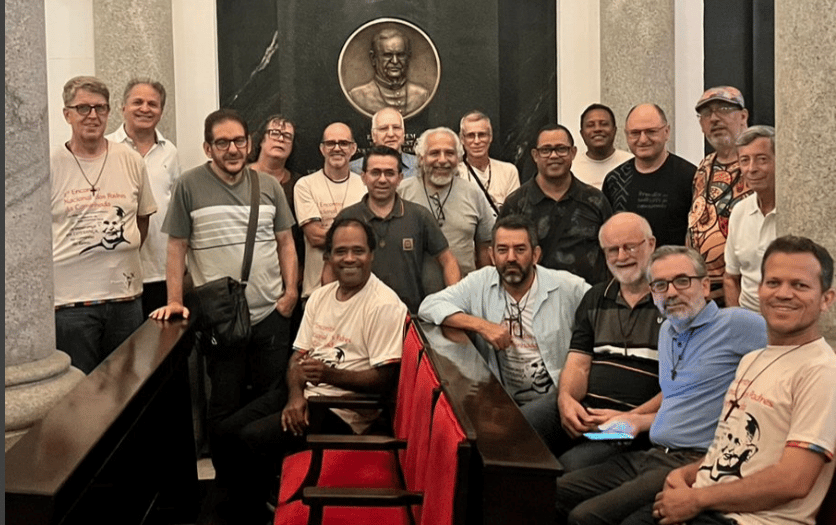

Formed under former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro (2018-2022), the Priests of the Path works not only as an ecclesial movement that puts pressure on the Church for reforms and on the government for sociopolitical change, but also as a space where ministers can talk frankly about their problems and expectations and share their fears and sufferings with their colleagues.

During their second national encounter last week, in São Paulo, the Priests of the Path discussed great national themes, such as the environmental destruction in the Amazon and the growing financial inequality in Brazil, and also ecclesiastical topics, including the search for new church models which could favor their pastoral work.

The building of a more synodal Church, one that can reduce historical problems like clericalism and ecclesial authoritarianism, was highlighted as a possible solution for the disturbances behind the suicide of priests.

“There are a few factors that increase the risks of a priest committing suicide. All of them are somehow connected to clericalism, a problem many times mentioned by Pope Francis,” said Father Lício Vale.

One of the major drivers of emotional distress among priests in Brazil is occupational stress, he said. The country’s total of 30,000 priests is considered strikingly low relative the overall Catholic population, with some experts claiming that Brazil would needs at least 80,000 priests to sustain the current ecclesial model.

“We work too much. You’re not only in charge of giving the sacraments, but you also need to work as a psychologist, a community organizer, a social worker, and so on. So much stress can rapidly become burnout syndrome,” Vale said.

Another central problem is loneliness. Most priests come from other cities and live alone at the rectory, without contact with their families and without real friends, he said.

“Especially for diocesan priests, ecclesial life can be an experience of living alone. Lay communities have difficulties to grasp the priests’ humanity. People would rarely invite their priest to take a beer. Most of them demand a certain attitude of correctness from him,” he said.

Priests end up assuming a superman attitude, Vale pointed out, requiring from themselves an almost unreachable individual level of moral faultlessness.

“All those aspects are reinforced by clericalism and can damage mental health,” Vale said.

He argued that in order to enhance the clergy’s quality of life and avoid mental health issues, the Church needs to implement changes in its ecclesial model.

“Synodality is a key element in that process, because it generates closeness. Walking side by side, the priest and his community are closer and his humanity is more easily recognized and experienced,” he reasoned.

Lício Vale believes that the Brazilian Church has been making progress in understanding the problems involved in clergy life and has been looking for ways to intervene.

The international effort to build synodality has been a central aspect in that process, de Proença affirmed.

“Clericalism suffocates the priests. The pope has been calling us to walk side by side because we need to listen more to each other and to be able to share our sentiments,” de Proença said.

In the opinion of Father Manuel Godoy, a member of the Priests of the Path and a theology professor at the St. Thomas Aquinas Institute in Belo Horizonte, many priests have been suffering with bureaucratic bishops who fail to really accompany them.

“Many bishops are only worried about their dioceses’ financial problems. There’s a deficit in humanity among them,” Godoy lamented. Synodality, he argued, would be a way of avoiding such distortions.

Godoy emphasized that the meeting of the Priests of the Path was itself an example of how the Church can be more healthfully organized.

“Many participants went back to their dioceses feeling that the meeting strengthened their commitment to the Church,” he declared.

“That happened because there we could face our problems in an honest way and fraternally discuss controversial topics like new ministries, for instance,” Godoy said.