SÃO PAULO, Brazil – Church organizations in Costa Rica are saying the state is not acting to help migrants after the tragic deaths of an Ecuadorian immigrant and her six-year-old daughter.

The 33-year-old woman was traveling on Feb. 28 with her daughter along with a group of seven people when the vehicle that was taking them to the Nicaraguan border, in the northern region of Costa Rica, fell into the River Medio Queso, near the city of Los Chiles.

Mother and daughter were the only passengers who were not able to escape, and their bodies were retrieved from the riverbed by divers.

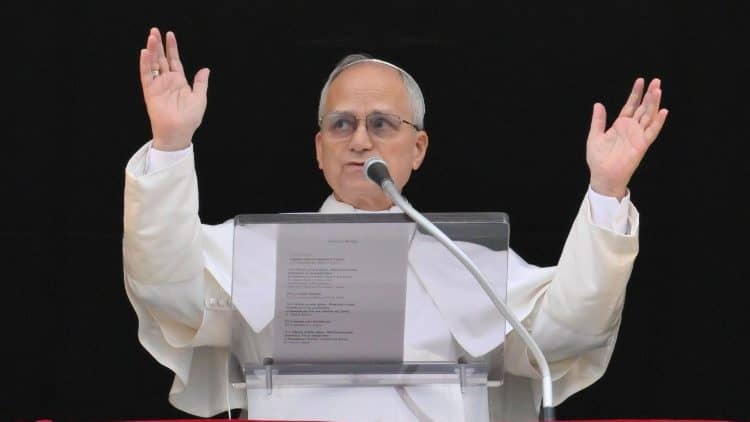

Father Luis Carlos Aguilar is a coordinator of the Latin American and Caribbean Ecclesial Network on Migration, Displacement, Refuge and Human Trafficking (known as Red Clamor) in Costa Rica.

“Their deaths are a signal of a general migrant crisis in Costa Rica. People have to walk through dangerous locations and end up being caught by criminals thanks to the lack of governmental action,” Aguilar told Crux.

The area where the accident occurred is notoriously part of the route used by criminal groups that illegally transport immigrants to the north towards the United States.

An agreement between Costa Rica and its southern neighbor Panama ensures that hundreds of immigrants who cross the Darien region – a dangerous zone of rainforest between Colombia and Panama – are taken to buses that transport them to the Costa Rican border.

From there, they can take another bus to the border with Nicaragua. But several problems may happen in that process, according to Church activists who assist the immigrants.

“Those buses are provided by the government, but the immigrants have to pay for their tickets. Those who don’t have any money end up taking other routes, and that can be risky,” said Aguilar, who is also the director of the Diocese of Puntarenas’s Caritas.

The buses final stop near Nicaragua is not on the border, but in a location fully controlled by criminals in which the immigrants have to take another means of transport, most of them operated by the gangs, explained Roy Arias, the coordinator of borders at the Jesuit Migrants Service.

“The ‘humanitarian’ buses provided by the government put the migrants in the hands of the criminals. At least 1,000-1,200 people arrive every day. And it happens every day,” Arias told Crux.

The zone is dominated by a mafia-like organization known as Los Talibanes, which controls drug trafficking and other illicit activities, including the irregular transportation of immigrants.

The migrant flux is not only formed by a majority of Venezuelans, Ecuadorians, Colombians, and Haitians, but also by people from African nations and from Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

“It’s a sad irony that Afghans who fled their country after the Taliban took over Kabul now end up encountering Los Talibanes in Costa Rica,” Arias said.

Brazil is one of the few nations in the world issuing humanitarian visas to Afghan refugees. But the South American country does not offer any kind of support to them, so most of the Afghans who arrive in São Paulo end up deciding to make the dangerous journey to the United States by land. On that trip, they are usually accompanied by immigrants from Southeast Asia and Africa.

Aguilar claimed the Costa Rican government has virtually transferred the responsibility for the immigrants to the Church and other civic organizations, given that it simply does not offer any assistance to them.

The crisis led the Jesuit Migrants Service to release a statement on Feb. 29 to urge the authorities to intervene.

“The Costa Rican State is obliged to act in order to reduce the numerous vulnerabilities of those who undertake the migratory journey. […] The obligation to identify and bring to justice the criminal groups that endanger the families traveling cannot be neglected,” the document read.

The public letter criticizes the Costa Rican press for failing to adequately inform the population about the crisis and about the responsibilities of the government in that context.

The declaration concludes by saying that the State must “predict the risks” and deal with the migrant crisis by defining “human rights as a priority, something that comes first to any other interest.”

Arias argued that the government must first of all “recognize that Costa Rica is part of an intense migrant route and that is not something temporary.”

“That crisis has been growing over the past ten years, but the authorities pretend that it’s transitory. They have to understand that it’s a structural situation and that policies are urgently needed,” he said.

However, some progress has been achieved. Aguilar explained that the government has agreed to declare a state of emergency and a budget has been defined to fund the necessary programs.

“But we still need the regulations that will determine how those programs will be executed,” he said.

In the meantime, Church groups have been intensifying their works with migrants. Last month, a center was opened by the Jesuit Migrants Service on the southern border. Nuns of different congregations have been working there.

At the same time, partnerships with other Christian denominations have been gaining strength.

“Without funds, we have been managing to multiply the bread and the fish for the work with migrants,” Aguilar said.

Arias said, however, that much work is still needed to raise awareness among the episcopate and lay Catholics about the migrant crisis.

“Unfortunately, many Catholics have been repudiating the immigrants and manifesting xenophobic opinions. Part of the clergy doesn’t want to get involved with them,” he said.