SÃO PAULO, Brazil – One year after the diary of a Jesuit describing more than 80 cases of child abuse came to light in Bolivia, the Society of Jesus repudiated the accusation that it’s a “criminal organization” and that it shouldn’t be blamed for the crimes.

The Bolivian Community of Survivors of Ecclesial Sex Abuse, however, reaffirmed that the Jesuits have institutional responsibility for “systematically covering up” over 400 cases, arguing that superiors and provincials were aware of the crimes.

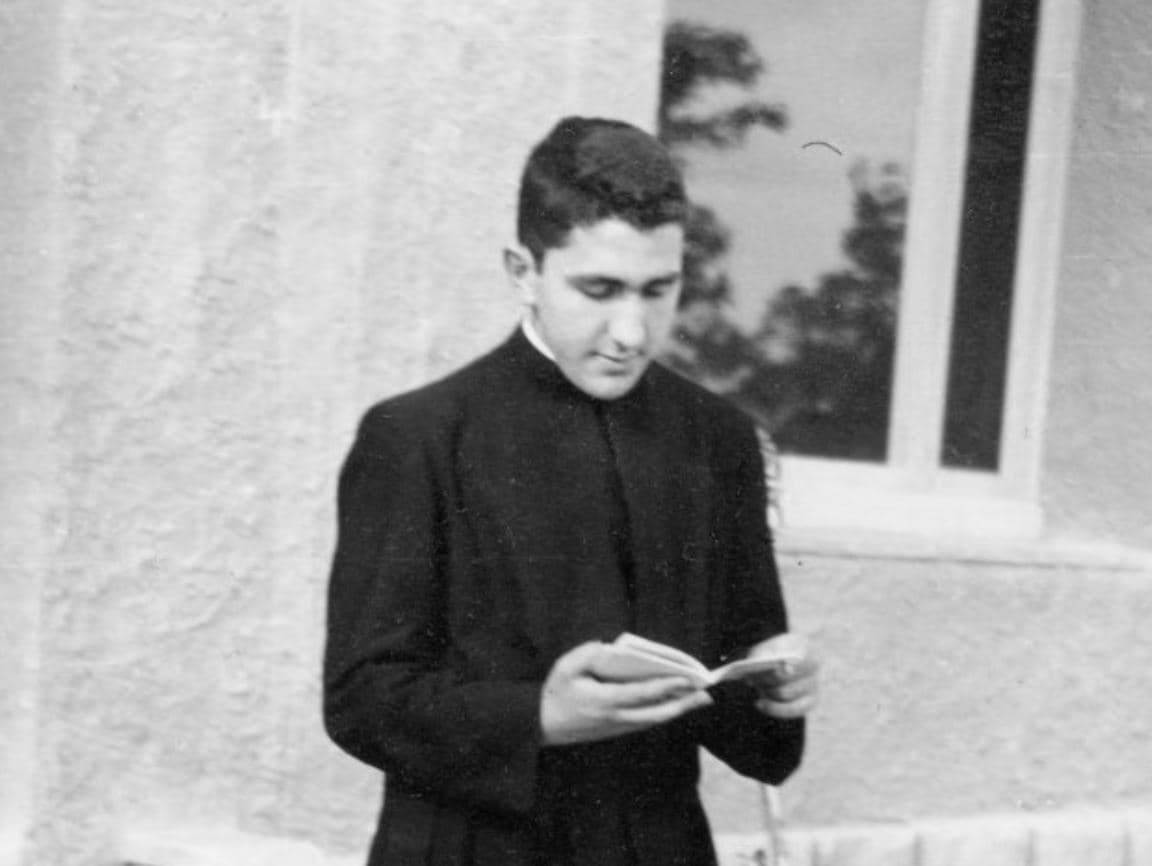

The diary of late Spanish-born Father Alfonso Pedrajas (1943-2009), known as Padre Pica, was first mentioned in a story published by Spanish newspaper El Pais in April of 2023. The article detailed how his writings were discovered by a nephew and then handed to the newspaper.

According to Pica’s diary, the first abuse happened in Lima, Peru, in 1964. Most of his crimes, however, took place when he worked at the John XXIII school in Cochabamba, Bolivia. It was a boarding school with hundreds of poor students coming from mining areas. His writings depicted how he would approach his victims at the dorm during the night, something that has been confirmed by some of them.

El Pais‘s story also emphasized that Padre Pica talked about his crimes with many of his colleagues and superiors, and that none of them reported him to the civil authorities. He was even advised by one of them to pray more for his own conversion.

At least eight Jesuits were criminally implicated in Padre Pica’s case. Two former provincials, Spanish-born priests Marcos Recolons, who is 81, and Ramón Alaix, who is 83, were put on house arrest at the end of March for allegedly working to cover up Pica’s crimes. The measure was later revoked.

While the revelation of Padre Pica’s wrongdoings has been the most scandalous crisis in the Bolivian Church in decades, other Jesuit priests have also been accused over the past couple of years for perpetrating or covering up pedophilia. That was the case of late Father Luis Maria Roma, who also used a diary to describe the abuse he perpetrated in the Santa Cruz region. The Bolivian Community of Survivors lists 11 Jesuit priests who supposedly committed abuse. Only two of them are still alive.

In its letter, released on Apr. 27, the Society of Jesus reaffirmed its “commitment so that the search for truth, justice and comprehensive care are effective towards the victims of sexual abuse committed by some members of the order.”

The document said that since Padre Pica’s scandal erupted, it has acted to work with officials to clarify the facts and determine responsibilities.

Only a few days after El Pais‘s publication, the order presented to prosecutors two other cases considered credible after canonical inquiries. One of them concerned Father Roma’s crimes, the other one was about Father Alejandro Mestre. The two are already dead.

The letter added that all Jesuits called by the Office of Justice to testify have worked with the authorities, something that was an institutional decision.

“Such a collaboration with Justice took place even when we considered some measures to be excessive, such as the several raids carried out at the Provincial Curia’s offices on the same day, or the application of precautionary measures like house arrest, later revoked, for the two charged former provincials, although there was no risk of escape,” the document read.

The Society of Jesus also declared that even before the scandal it had been working on policies of violence prevention, which included an established protocol and communication channels for victims to denounce crimes. Last year, the statement continued, such effort was intensified with the approval of a set of policies and protocols for sex abuse prevention and the strengthening of its listening and attention channel, directed by a lay professional.

The letter emphasized that the Society of Jesus “rejects accusations that it is a ‘criminal organization’,” which fancifully describe “institutional forms, procedures and actions that would show ‘systematic pedophilia and cover-up’ everywhere, as if it were a constitutive part of the religious order,” it said.

“[The Society of Jesus] categorically denies having any institutional responsibility in cases of abuse that some of its members have committed or allegedly covered up. These are personal responsibilities that each one must face before justice,” the document added.

The Bolivian Community of Survivors of Ecclesial Sex Abuse “received the Society of Jesus’s letter with sadness,” according to Edwin Alvarado, one of its founding leaders.

“For us, it’s a simple case: If the Society of Jesus had timely denounced those predators, they’d have been detained by Justice and hundreds of kids could’ve been saved from abuse. Their omission makes them institutionally responsible,” Alvarado told Crux.

He added that the Jesuits’ communication channels “only work to discourage the victims, so they give up taking their cases ahead and the aggressors end up remaining unpunished.”

“Victims that sought help through those channels were soon abandoned. It’s a theater. They have a legal team that generates false hopes,” Alvarado added.

He said that the Community of Survivors has been welcoming people who received psychological attention from the Jesuits and told it that it was insufficient.

On Apr. 30, the Community of Survivors released a statement with harsh criticism of the Jesuits’ letter. It said that the Society of Jesus systematically covered up abuse and that it has institutional responsibility for the crimes perpetrated by 11 of its members in Bolivia.

The letter also criticized the measures taken by the Jesuits in order to deal with the victims, including the communication channels.

“We affirm that the Society of Jesus with its ‘internal listening channels’ usurp functions that correspond to the Prosecutor’s Office and the Bolivian Judicial system. The Society of Jesus attributes to its ‘prior information’ the power to establish the complaints’ ‘verisimilitude’, and that is the sole responsibility of the Prosecutors’ Office,” the declaration read, adding that the Jesuits can’t be the judge and a party in the same lawsuit.

The Community of Survivors concluded the letter by saying that it hopes the prosecutors will demonstrate that the Jesuit priests, with the support of their organization, perpetrated crimes against humanity and victimized a vulnerable population of children with the protection of their superiors.

In the opinion of sociologist Julio Cordova, an expert in the religious dynamic in Bolivia, the Jesuits’ wrongdoings in the time when most of the abuses happened – the 1970s and the 1980s – were part of a broader context that led the Catholic Church as a whole to downplay and cover up sex abuse.

“The Jesuits prioritized their institutional image and not the reparation to the victims. That was how the Catholic Church used to deal with abuse,” Cordova told Crux.

At the same time, civil society still didn’t have a culture of denouncing and supervising institutions like the Church, “something that has been majorly boosted by feminism over the past few decades,” he added. Those factors led to decades of silence, till the 2023 scandal.

In the present context, the Jesuits made other serious mistakes, according to Cordova. One of them is that they only brought Padre Pica’s and other members’ cases to the authorities after El Pais’s publication.

The other is that they keep resorting to canonical inquiries and lawsuits before reporting crimes to the judicial system.

“That practice – which is also a practice of the Church as a whole – can delay justice to be served, revictimize the denouncers, and lead to cover-ups. Canonical processes are authoritarian and colonialist,” Cordova said.

Despite those problems, he thinks that the Society of Jesus is right to adopt anti-abuse policies and to create communication channels for the victims to denounce. Cordova also said the Jesuits have been mostly cooperative with the Judiciary now. He categorized the Jesuits’ reaction to the abuse scandal inquiry as “lukewarm to moderately cooperative.”

“But Bolivia still hasn’t created an independent commission to investigate Church abuse, as some people suggested after Pica’s scandal,” he said.

A member of a polls institute, Cordova said that a survey conducted last year showed that almost 50 percent of the Bolivians considered that the Church covers up abuse.

“Especially young, middle-class residents of the Western part of the nation have that perception,” he said.