ROME – While many have taken the strange case of Argentine ex-priest Ariel Alberto Príncipi as a classic example of a turf war between competing Vatican departments, a close analysis suggests the twists and turns may be less about bureaucratic tussles and more about the notoriously ill-defined boundary between misconduct and outright abuse.

As part of that picture, the Príncipi case also illustrates how one of main tests in ecclesiastical jurisprudence for establishing abuse, which is whether a particular act was carried out “for libidinous ends,” can be exceedingly difficult to prove.

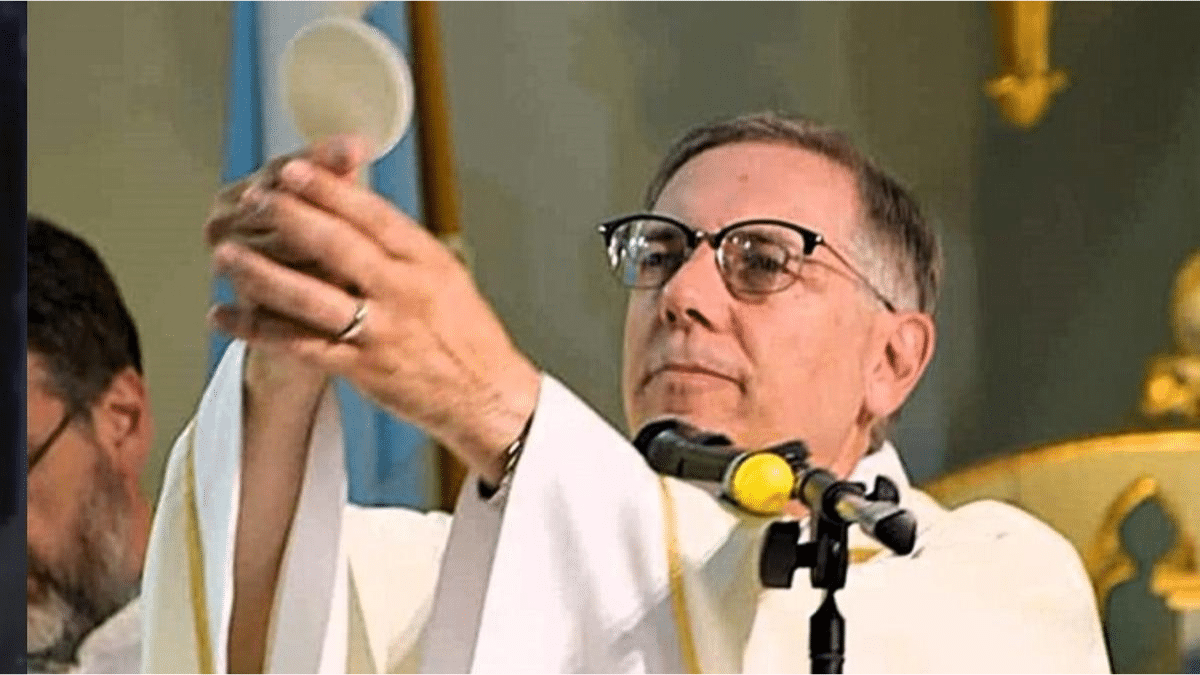

In 2021, Príncipi was accused of sexually abusing minors while performing “healing prayers” for homosexuality associated with a Catholic charismatic movement. His case was sent to the Vatican’s Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF), which handles sexual abuse matters, and the dicastery subsequently authorized local tribunals to conduct a trial.

Príncipi was found guilty by an interdiocesan tribunal in Córdoba, Argentina, in June 2023 and ordered to be returned to the lay state. He immediately appealed the ruling, which was confirmed by an interdiocesan tribunal in Buenos Aires in April of this year. The tribunal also upheld the order of expulsion from the priesthood.

In September, Bishop Adolfo Uriona of Río Cuarto, Argentina, where Príncipi served, told local media that they were only awaiting final confirmation of the sentence from the DDF, after the formal window of appeal had closed, in order to impose the sentence.

Yet just days later, on Sept. 25, the Diocese of Río Cuarto announced instead that it had received an edict from the Vatican’s Secretariat of State signed by the sostituto, a position akin to a chief of staff and which is currently occupied by Venezuelan Archbishop Edgar Peña Parra, ordering Príncipi’s reinstatement as a priest under restricted ministry.

The Vatican’s communique, a portion of which was published on the Diocese of Río Cuarto’s website, stated that “as a result of further evidence provided by some diocesan bishops of Argentina, as well as by several faithful” in June and July, on July 5 “an extraordinary procedure was initiated, with suspension of the previous decision.”

The communique did not say who presented the evidence or what it consisted of, and nor did it explain what “extraordinary procedure” was followed.

The communique said “several penal measures” had been ordered against Príncipi, who was “considered very imprudent in the exercise of the so-called ‘healing prayers.’” He was reinstated as a priest but barred from having contact with minors, from exercising pastoral ministry in the Catholic charismatic renewal, and from exercising full pastoral care of a church, and was prohibited from celebrating or concelebrating Mass publicly.

Then, in another surprising turn, just two weeks later the reversal was itself reversed. On Oct. 7 Archbishop John Kennedy, head of the DDF’s disciplinary section, issued a new decree published by Río Cuarto stating that Peña Parra’s previous edict was void, and that Príncipi’s defrocking remained in effect.

In that communique, portions of which were also published on the Diocese of Río Cuarto’s website, Kennedy said the “extraordinary procedure” resulting in the reversal of Príncipi’s laicization was “carried out outside the scope of this dicastery,” and that it “has been annulled.”

“The case is again subject to the ordinary process in this dicastery, according to the rules provided for by the law of the church,” the statement said, adding that no legitimate appeal against Príncipi’s defrocking had been filed in the DDF within the legal timeframe.

Príncipi’s previous condemnation and sentence “must be considered in force in all its parts,” Kennedy said, and that consequently, “The case has been closed.”

Given the tit-for-tat between the Secretariat of State and the Dicastery for the Faith, which for centuries have battled one another for supremacy in the Vatican system, it’s understandable why many observers have concluded this is another chapter in that long-running rivalry.

However, the original sentence issued by the interdiocesan tribunal of Córdoba, which sources in Argentina have shown to Crux, indicates that the back-and-forth could have more to do with the murky line between mere imprudence, or poor judgment, and actual abuse.

Most of the allegations against Príncipi consisted of groping during so-called “healing prayers.” According to testimony, Príncipi would lay his hands on various parts of the body, including the genitalia, while praying for the individual to be cured of homosexual tendencies.

For the most part, these prayers were performed on adults and in the presence of other people.

The allegations came from three individuals who said they were in their late teens, most between 17 and 18, when Príncipi manipulated them into receiving the prayers and groped them while it happened.

Throughout the process, Príncipi maintained his innocence, insisting that there was nothing sordid about his intentions, and that the prayers were meant for healing, rather than sexual gratification – thus not for “libidinous ends,” as generally required for a finding of abuse.

The question of whether Príncipi drew pleasure from the imposition of hands on the genitalia was one of the main topics of debate, with the initial sentence finding Príncipi guilty not only of sexual abuse, but also abuses of power and manipulation.

However, some legal experts familiar with the case who spoke to Crux said they found that sentence to be subjective and based on claims that are difficult to substantiate, leaving considerable room for doubt. On the whole, these experts voiced a belief that while Príncipi was certainly imprudent and deserved some form of sanction, dismissal from the clerical state may have been exaggerated, especially for what appeared to be more a lack of good judgment than outright criminal intent.

The general consensus was that in the Latin American context, which holds different standards than other areas of the world such as the United States, the penalty was disproportionate to the actual alleged crime.

Thus, the conflicting messages from the Vatican’s Secretariat of State and the DDF could be less about curial offices marking their territory, and more about internal doubts regarding the charges and the appropriate penalty to impose.

What now seems clear is that Príncipi has indeed been defrocked. Beyond his personal fate, however, the case stands as a reminder that a quarter-century after the clerical abuse scandals first exploded in Catholicism, the precise dividing line between imprudence and abuse still remains elusive.