SÃO PAULO – President Donald Trump’s new policies concerning undocumented immigrants have been causing shock and outrage among many in Latin America.

The region’s Church is one of the institutions currently trying to figure out how such changes will impact its work and is establishing strategies to deal with them.

The new U.S. president’s pledge to promote “mass deportations” and the scandalous ways his administration has been enforcing his policies were received with criticism in Latin American countries like Brazil.

On Jan. 24, the first plane with 88 Brazilian deported immigrants arrived in Manaus, Amazonas state. Footage of handcuffed passengers and reports of violence on-board – some of them said they were beaten up by U.S. security officers when they complained about the lack of air conditioning inside the plane – sparked controversy all over the country.

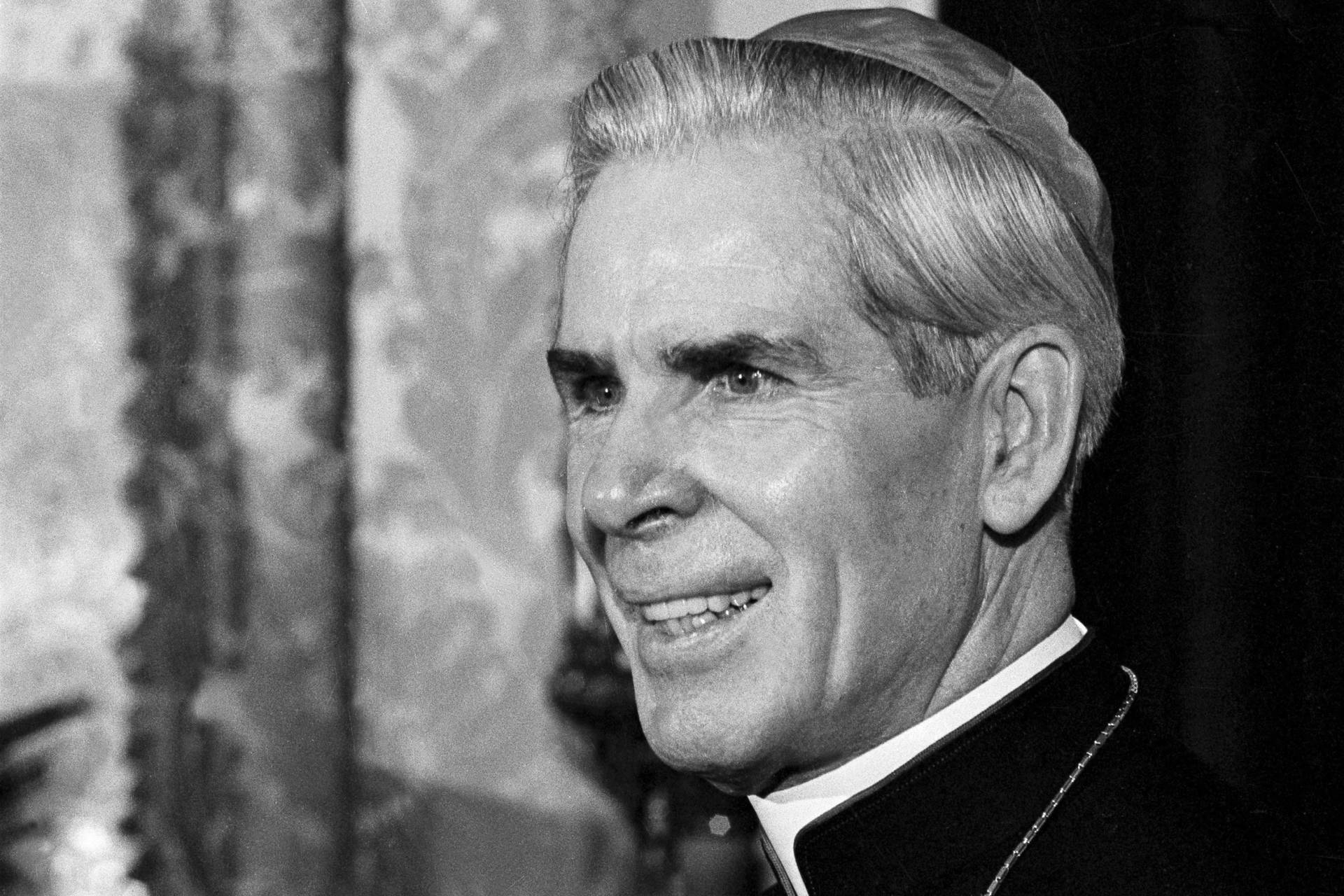

Latin American bishops like Archbishop Roberto González Nieves of San Juan, Puerto Rico, and Archbishop José Domingo Ulloa Mendieta of Panama City, emphasized that the new U.S. immigration policies should consider the needs and the rights of the immigrants. Ulloa said that the new rules will transform the borders into “human dams.”

A high number of Catholic groups work with migrants in Latin America. Not only congregations like the Scalabrinians, whose charism is precisely to assist refugees and immigrants, promote actions to help people crossing the region towards North America. Orders like the Jesuits and the Verbites also keep temporary shelters and refectories along the way, as well as numerous parishes, dioceses, pastoral ministries, and Caritas organizations.

One of the recent initiatives aiming develop strategies to deal with the new situation was an online meeting promoted by Red Clamor (Latin American and Caribbean Ecclesial Network on Migration, Displacement, Refuge and Trafficking in Human Beings), which gathers dozens of Catholic groups, on Jan. 31. More than 100 people discussed the challenges posed by Trump.

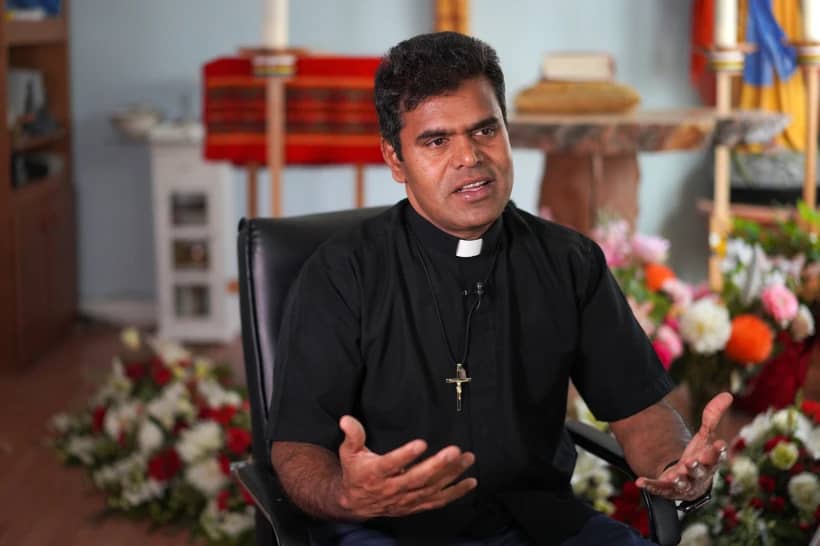

“The new measures’ impacts are manifold. They menace people now traveling to the U.S., people who have been living there for decades, and institutions that directly or indirectly receive money from the U.S.,” Bishop Eugenio Lira of Matamoros, Mexico, who heads the Mexican Human Mobility Pastoral Ministry, told Crux.

Lira was one of the meeting’s speakers, and emphasized the raids in schools, companies, and even churches with the goal of detaining undocumented immigrants put at risk numerous families. At the same time, they harm the lives of uncountable people, who from one day to another simply had to cease frequenting some places in order to avoid deportation.

“Some immigrants have been living for two or three decades in the U.S. When they’re deported to their original countries, many times they don’t have family or friends there anymore,” Lira said.

Red Clamor debated forms of enhancing its organization and came up with suggestions on how Church groups can help.

“Against all odds, we’re marching together. We’ll keep offering physical, psychological, and spiritual counseling to immigrants, as well as promoting their education, work, sheltering and so on,” Lira said.

One of the key moves now is to enhance the dialogue between different Church organizations, as well as to promote alliances with Catholic educational institutions, parishes and dioceses, he added.

“If donations from the U.S. will not arrive anymore in Church projects, we must look on the local level for new alliances with governments, businesses, and Catholic entities,” Lira said.

Indeed, a few projects might be discontinued in the short term, like an initiative promoted by a local Caritas in the Amazonian region, in Brazil, which is totally funded by a United Nations organization – which will cease to receive U.S. money, if Trump keeps his word.

“At this moment, we’re still waiting to see how things will evolve. Our fear is that too many actions could be interrupted,” Scalabrinian Father Paolo Parise told Crux.

An Italian-born missionary in Brazil, Parise heads Missão Paz (Mission Peace), a center for refugees and immigrants in São Paulo. He said its works have been receiving funds from different donors, so it’s not at risk like other Catholic initiatives.

“Unfortunately, some institutions depend almost exclusively on the United Nations, for instance,” he said.

Parise argued that Trump’s measures are a spectacular act for his backers. They are planned to be brutal and scandalous, causing fear among the undocumented immigrants and a sense of rejoicing for his supporters.

“But we have to remember that the Democrats, although less loud, have also deported people massively. [Former President Barack] Obama, for instance, deported more people than Trump [in his previous tenure],” he said.

While the new policies will probably reduce the migratory flux for some time, they will not block it for long, he added.

“People will always continue to come up with ways to go to the U.S. and Canada,” Parise said.

Last week, he met with a group of Afghan refugees at São Paulo Airport. Brazil has been the only country in the world to issue humanitarian visas for Afghans since the Taliban took over Kabul, and many of them remain at the airport for some time when they arrive in Brazil, until they figure out where to go.

“Only a handful of them told me they want to remain in Brazil. Most of them want to move to North America,” Parise said.

In the opinion of Father Conrado Zepeda, a Social Science professor at the Ibero American University in Puebla who headed the Jesuits’ migration and refugees service for years in Mexico, the Latin American Church is “on the immigrants’ side, more than ever.”

“More conservative parishes or groups that didn’t have any work connected to immigrants have been launching initiatives over the past few years, thanks to Pope Francis’s insistence on that theme. The Latin American Church is almost unanimous now in that regard,” he told Crux.

Zepeda also thinks that maybe the Trump administration will not carry out millions of deportations.

“The immigrants are an additional element in the economic and political negotiations of the great powers. But the brutality of the process will cause much trauma,” he said.