SÃO PAULO – Thirty-eight years after the brutal killing of Spanish-born Jesuit missionary Vicente Cañas in the Amazonian State of Mato Grosso, the Brazilian judiciary finally issued an arrest warrant against one of the murderers.

Ronaldo Osmar, a local police deputy, was found guilty of killing Cañas in 2017. Only this month the deadline for any kind of legal appeal was finally over, which means that now Osmar should begin the fulfillment of his sentence. Given that he’s old and has been hospitalized, his imprisonment still depends on his health conditions.

“Such indefiniteness doesn’t bother me. The important thing is that he was convicted and nothing can change that,” Sebastião Carlos Moreira, a pastoral agent of the Bishops’ Conference’s Indigenous Missionary Council (known as CIMI), told Crux.

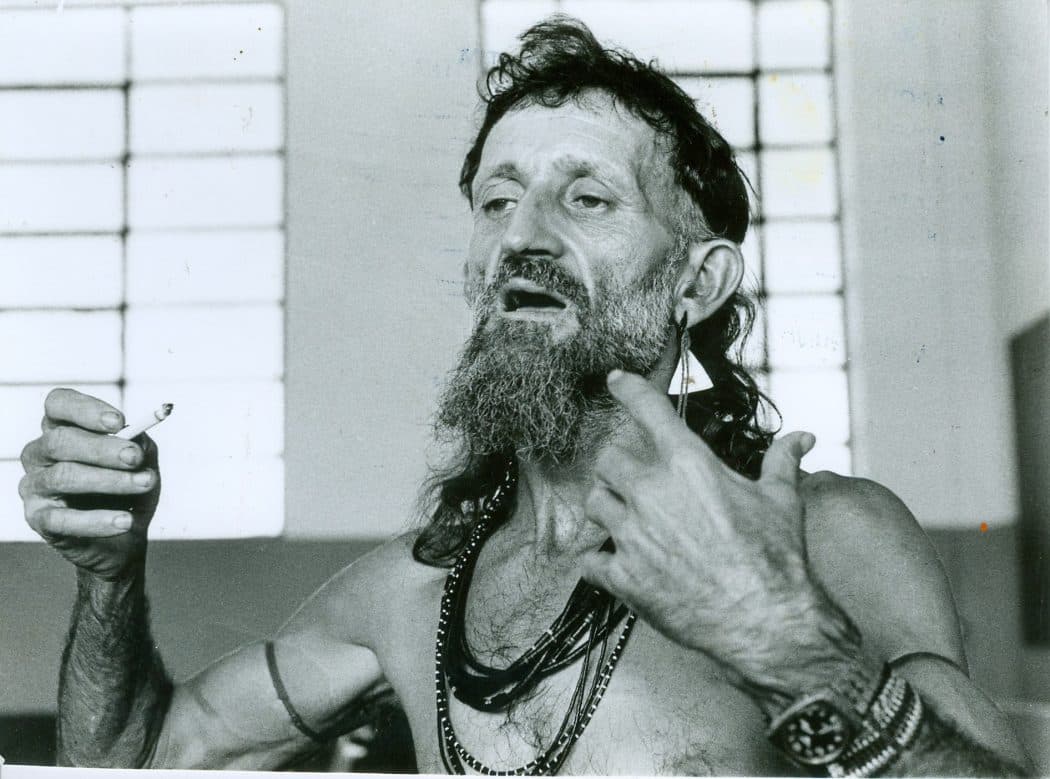

Born in Albacete, Spain, in 1939, Cañas joined the Society of Jesus and came to Brazil as a missionary in 1966. In 1969, he began working with Indigenous groups in Mato Grosso.

“We first met in 1978. At that point, he had already established contact with the Enawenê-Nawê a few years before,” Moreira recalled.

Until then, the Enawenê-Nawê didn’t have real contact with the surrounding society. Their traditional lands hadn’t been recognized by the government and ranchers and loggers invaded their territory.

Cañas lived with them for 10 years, learning their language and habits. He became part of the work group that would present to the government the parameters for the definition of their territory.

“Of course, ranchers were very interested in their lands. Seeing Cañas’s work for their protection, they quickly began targeting him and threats became common,” Moreira recalled.

At a certain point, Cañas himself would warn his friends that his life was in danger. Indeed, in April of 1987 he ended up being killed in his hut, 37 miles away from the Enawenê-Nawê village. He was there alone in quarantine, waiting to join them once again. His body was found only 30 days after the murder.

With his death, a long wait for Justice would begin. The problem is that the police inquiry into his murder was headed by deputy Ronaldo Osmar, who was a major suspect. He would do everything he could to cause delays and impede the investigation to go on.

A bizarre chapter of the inquiry happened in 1989. Cañas’s body had already been examined by forensic experts in Mato Grosso state, but for some reason his skull was sent to further analysis in Minas Gerais State. There, it was declared missing. The skull would be found on the street later, inside of a small box, by a shoeshine boy.

“While the process was being conducted by the local justice, it didn’t move. That’s why we fought for its federalization,” said Moreira.

One of the reasons for its transfer to federal justice was the fact that Cañas was representing the Brazilian government as a member of the Enawenê-Nawê land grant work group. The new suit started in 2015 and resulted in Osmar’s conviction two years later.

According to CIMI, one of the key elements in the jury was the participation as witnesses of members of the Rikbaktsa Indigenous group. The Enawenê-Nawê people have a cultural interdiction that impedes them to mention dead people, so they weren’t able to talk about Cañas in court. The Rikbaktsa agreed to do so and provided new evidence.

If the legal process took so much to be concluded, for the Amazonian Church Cañas would quickly become a major martyr, side by side with other missionaries who lost their lives in land disputes in the region, like the U.S.-born Sister Dorothy Stang (1931-2005) and Father Josimo Tavares (1953-1986). During the Synod for the Pan-Amazon region (2019), he was recalled by many of his friends on several occasions.

“He was a very humane person. He would never conform to any kind of injustice. He had the utopia that we would build a fraternal world and died for it,” Sebastião Moreira said. “For me, he was a model in the way he conducted his life and his faith.”

Among the Enawenê-Nawê, Cañas has never been forgotten. Tragically, part of his struggle was for the demarcation of their lands in the region of Preto River, an ancestral territory where the spirits of three of the group’s clans are thought to inhabit. Such an area is now occupied by farms.

“And part of the lands officially granted to them [in 1996] are now invaded by ranchers and illegal loggers,” Moreira said.

Some of Cañas’s Jesuit colleagues said Justice will only be served in his case when invasions like that cease to happen in Brazil. Unfortunately, that seems to be an even more distant scenario.