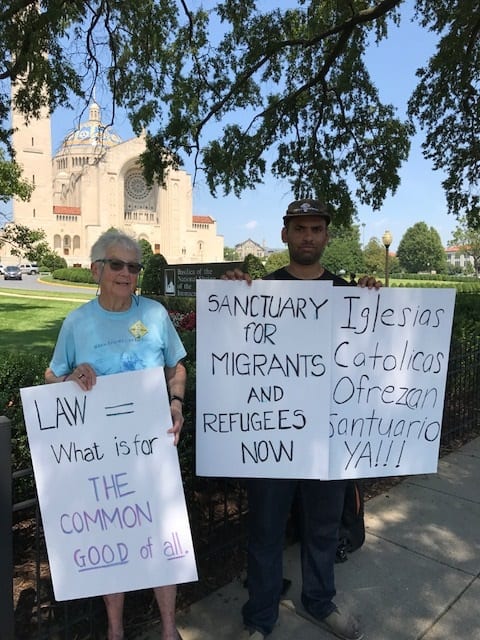

When Sister Megan Rice was contacted by immigrant rights activist Felix Cepada to join forces in a hunger strike at the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C. this week, she didn’t hesitate to say yes—despite being 87 years old.

On Monday, Cepada, along with Rice and other activists, commenced a hunger strike in an effort to bring greater awareness to the plight of undocumented immigrants and to promote the sanctuary church movement.

In a letter sent to Cardinal Donald Wuerl of Washington, D.C., Cepada wrote “The Catholic Church in the United States provides amazing services to the poor and we have to celebrate that…. At the same time, we have a great capacity to offer sanctuary to immigrants facing deportation.”

In an interview with Crux, Cepada said that they are requesting a Catholic sanctuary church in Washington, D.C., and one in every diocese in the United States.

Cepada, age 36, was born in the Dominican Republic and is a former Jesuit brother. In June 2016, he began protests in front of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in New York. The protests were followed by hunger strikes in front of Cardinal Timothy Dolan’s Madison Avenue residence before heeding his doctor’s advice to take a break due to his borderline diabetes.

While Dolan did not personally acknowledge Cepada’s request, Monsignor Kevin Sullivan, head of the archdiocese’s Catholic Charities office, issued a statement.

“The parishes, schools, and the charitable agencies of the Archdiocese have been welcoming immigrants to the United States for more than 200 years. We intend to continue and strengthen that legacy,” he said.

“We started the dialogue in New York, which hasn’t ended because Cardinal Dolan hasn’t said no, but we thought it would be important to continue the dialogue in D.C. because the U.S. bishops are here,” Cepada told Crux.

Cepada arrived in Washington from New York on Monday, August 21, and is now staying with Rice at the Society of the Holy Child of Jesus convent.

For Rice, welcoming immigration activists was a continuation of her decades long social activism which she traces back to a visit from Dorothy Day to her home at age three. Rice’s father was an obstetrician who volunteered as an advocate for abused pregnant women and her mother was an historian at New York’s Hunter College who wrote a thesis on American Catholic opinion on slavery.

“This led me to always have a concern for racial prejudices,” she told Crux.

Rice is a well-known Catholic activist who has been arrested some 40-50 times, most notably for breaking into a national nuclear reserve in 2012 in what was labeled the “biggest security breach in the history of the nation’s atomic complex.”

Rice, however, offers no apologies.

“This work should never be called civil disobedience,” she told Crux. “This is civil obedience because we are obeying the common good.”

The idea of sanctuary churches dates back for centuries, as churches have widely been viewed as a place for those seeking protection from the state. In the 1980s, the movement grew widely in the United States among various faith traditions seeking to support refugees fleeing civil war in Central America.

Since the November 2016 presidential election of Donald Trump, the movement has resurfaced in protest of the administration’s immigration policies.

According to data from the Pew Research Foundation, there are 11 million unauthorized immigrants in the United States. While Catholic leaders have been among the leading vocal opponents of Mr. Trump’s deportation efforts, they have also been wary to join the sanctuary church movement.

In an interview with the Washington Post this past March, Wuerl offered a measured assessment of what the Church could promise immigrants seeking sanctuary.

“When we use the word sanctuary, we have to be very careful that we’re not holding out false hope. We wouldn’t want to say, ‘Stay here, we’ll protect you,’” he said.

“With separation of church and state, the church really does not have the right to say, ‘You come in this building and the law doesn’t apply to you.’ But we do want to say we’ll be a voice for you,” he continued.

That same month, Cardinal Blase Cupich of Chicago issued a letter to the priests of his diocese instructing them not to open the doors of their parish facilities to immigration agents without a warrant.

“If they do not have a warrant and it is not a situation that someone is in imminent danger, tell them politely they cannot come on the premises,” he wrote. Cupich, however, said that priests should not offer their facilities as sanctuary spaces, stating that only priests and those approved by the archdiocese could reside on Church property.

“We’re going to stay here as long as possible,” Cepada told Crux. “We have so many parishes, and we haven’t even offered one. We have empty churches and closed churches, and we need to offer one, especially here in Trump’s backyard. I think it would be very prophetic.”

When asked for comment on Cepada’s letter, the Archdiocese of Washington provided the following statement to Crux.

“The Catholic Church strives to help all who seek pastoral care, spiritual guidance, and material assistance. As our Holy Father, Pope Francis recently noted, ‘Every stranger who knocks at our door is an opportunity for an encounter with Jesus Christ’,” the archdiocese said.

“The parishes of the Archdiocese of Washington and Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese are welcoming to all in need of assistance. We accompany those who seek help, whether material, legal, or pastoral. That is our calling as Christians, and that is what we do every day.”