WASHINGTON, D.C. — After the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, near St. Louis, in the summer of 2014, Catholic organizations in the Archdiocese of St. Louis took a long, hard look at what they were doing to serve poor communities in the archdiocese — and what they could be doing better.

More than three years after the killing, and the cycle of protests that sprang up in its wake, there is not only more collaboration within the archdiocese, but also between Catholic agencies and other public and private groups who share at least in part a similar mission.

That was the assessment of four speakers from the archdiocese as they unspooled a “best practices” workshop Feb. 4 during the Catholic Social Ministry Gathering in Washington.

“What drives wealth inequality, which is far bigger than income inequality?” asked Ray Boshara, of the archdiocesan Peace and Justice Commission. He said there are three economic drivers: “The year you were born, race/ethnicity and education.” He said he also suspects two-parent vs. one-parent families and gender also have a part to play, but the first three factors have data to back them up. And those factors, Boshara said, count for more today than they did a generation ago.

The region also is split between “thrivers” and “strugglers,” Boshara added. Thrivers, about one-third of the population, may have lost a little wealth at the onset of the Great Recession, “but they’ve more than made up for it,” he said, while strugglers “haven’t gotten back to where they were” when the economic downturn happened a decade ago.

The archdiocese is working on three priorities to beat back inequality: providing early childhood education (“the numbers are amazing,” Boshara said); raising money to put $500 to $1,000 in an interest-bearing savings account for newborns to use once they reach college; and addressing “racial equity, primarily through dialogue and relationship-building,” he added. “We think relationships are important and we’ve done things to foster that in the St. Louis area.”

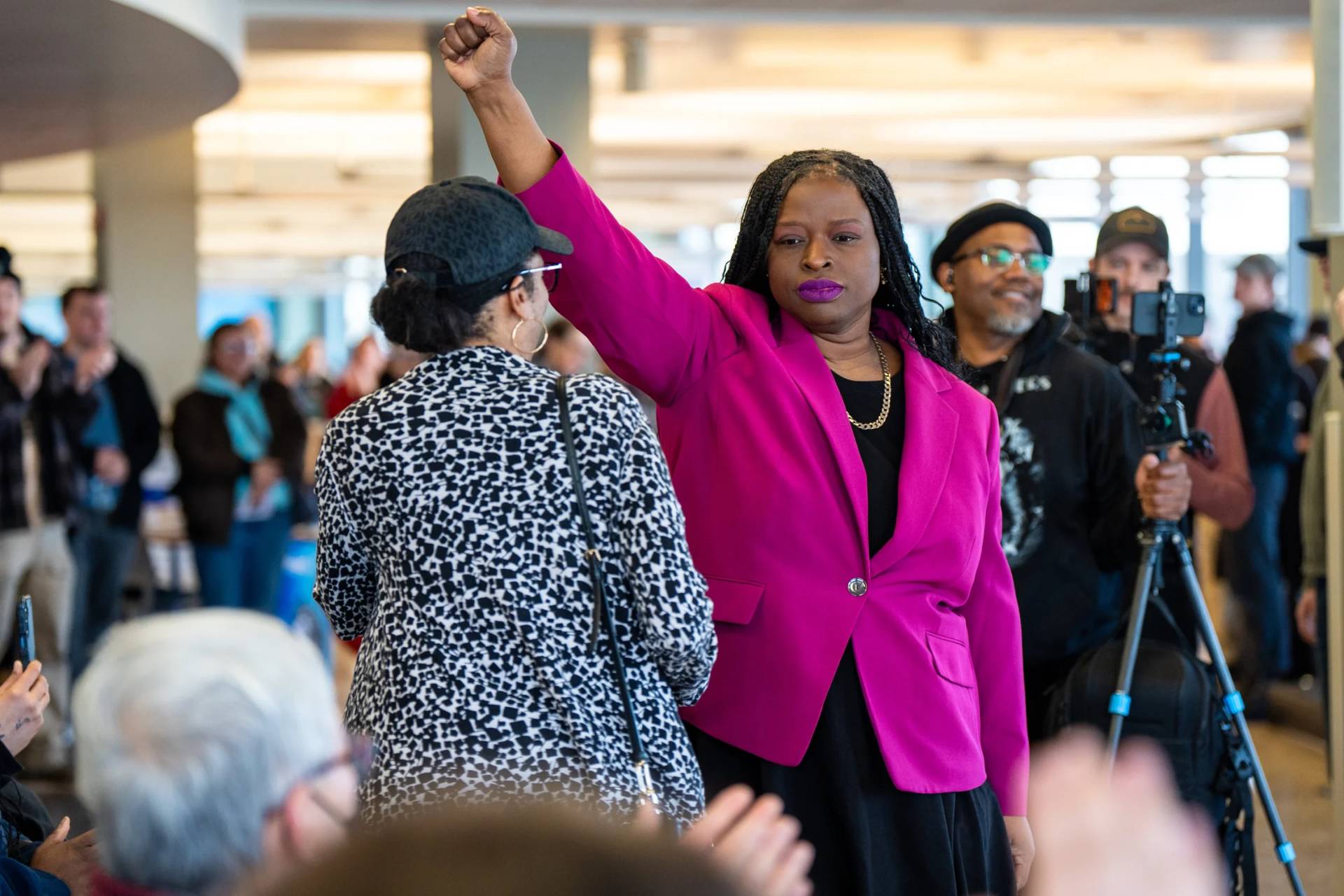

Lynn Squires, president of the board of directors of the St. Charles Lwanga Center, the archdiocesan ministry to black Catholics, didn’t expect to return to her hometown. But “what do you do when your city blows up?” she asked. “I had no plan. God had a plan. He ordered my steps.”

The center looked at what it did and saw that it was fulfilling its mission, but it also saw very little overlap with everything else going on in the archdiocese. The center, according to Squires, has since made it a point to be a part of more archdiocesan activities, and expects reciprocity. “We are not a problem to be fixed,” she said. “We are the solution.”

Tyrone Ford, director of service integration for Catholic Charities of St. Louis, said an internal assessment of its eight affiliate agencies shortly after the Ferguson unrest prompted the decision to seek closer collaboration with other agencies, both private and public, to make a more profound difference in the lives of the poor, particularly in nine poverty-dominant ZIP codes in northern St. Louis County.

The result: “Pathways to Progress,” a partnership between Catholic Charities and six other agencies in the area, including the YWCA, the Urban League and the Society of St. Vincent de Paul. The YWCA, for instance, provides early childhood education services, while another agency provides services for children from kindergarten through eighth grade. The numbers are not huge — 30 last year, 44 this year and 75 next year — but Ford said it’s having a positive impact.

In asking the poor in St. Louis their biggest needs, transportation — the expected top choice — came in second to legal services. “They had a lot of legal issues that were preventing them from obtaining housing, employment and transportation to get them to that employment,” Ford said.

The point of the initiative, Ford added, is to “stop the relation of client (and provider) and take ownership of your life to be prosperous, and not in poverty.”

Tamara Kenny, director of advocacy and engagement at Catholic Charities, said that for exiting clients of its member agencies, “health was their greatest concern. … Poor mental health was the single biggest obstacle their clients faced.” On top of that, she added, are the “racial health disparities that exist in our state.”

Blacks are seven times more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia; 5.5 times more likely to get asthma; 3.9 times more likely to have hypertension; 3.2 times more likely to get eye infections; and more than twice as much as others to have diabetes and epilepsy, to get inadequate prenatal care and to face infant death.

“There are higher rates for cancer, kidney disease, stroke and diabetes,” Kenny said. Blacks in Missouri live five years fewer on average than do whites, she added.

Even so, “Missouri has the third most restrictive Medicaid eligibility requirements for parents,” Kenny said. “Racism itself can be a toxic source of trauma.”

Boshara said St. Louis Archbishop Robert J. Carlson sent a letter to priests in the archdiocese, asking them to talk about racial issues in their homily for the first Sunday of Lent. The archbishop included homily aids and web links with his letter, but some pastors are reportedly shying away from the task.