CHICAGO — Ke’Shon Newman’s daily routine is guided by guns — the hundreds of illegal pistols, revolvers and other firearms that torment his South Side neighborhood.

He walks on brightly lit streets, the ones lined with Jamaican jerk and seafood joints, minimarkets, the White Castle, a Shell gas station. If shooting erupts, he wants witnesses — and, if necessary, help. He listens to music with one earbud, to hear approaching footsteps, and avoids clothing with hoods that might block his peripheral vision.

These are the rituals of a street-smart 16-year-old who knows the cruel meaning of wrong place, wrong time. His stepbrother, Randall Young, then 16, was killed in crossfire two years ago while walking his girlfriend to a bus stop. “Nine shots,” Newman says, words that need no embroidery. “I’m making sure my mom doesn’t have to lose another child.”

The Auburn Gresham neighborhood is flooded with illegal guns: .40-caliber pistols, .380 semi-automatics, .38-caliber revolvers. Police recover as many as they can, searching apartments, stopping cars, cornering people on the street. A buy-back in June brought in hundreds of firearms. And in September, the mayor and other dignitaries gathered to mark a milestone: Police in the 6th District had recovered their 1,000th gun this year.

It was a triumphant moment, but it also offered a glimpse into the overwhelming task faced by law enforcement — and the wounds inflicted on just one Chicago community — when guns are readily available and violence so common that, one study found, an estimated 1 in 2 young men had at some time carried firearms, almost always illegally. Most did so to stay safe.

“I tell people all the time we don’t have post-traumatic stress. We have PRESENT-traumatic stress,” says Father Michael Pfleger, the activist priest at St. Sabina Church who was the inspiration for a character in Spike Lee’s “Chi-Raq.” ”We’re still in the war. We’re not coming home from it. We live it.”

Chicago’s gun violence has captured the national spotlight in recent years and President Donald Trump has, at various times, blamed the Democratic leadership, threatened to send in federal troops and breezily called the problem “very easily fixable.”

Those who battle this daily in the 6th District see it much differently. Guns not only shatter families, they determine what time people leave their houses, the streets and stores they avoid, whether a church should have a metal detector, even whether a Ferris wheel operator feels it’s safe enough to install a ride for a festival.

Residents in the community often know who’s behind shootings — there’ve been nearly 600 since 2016 — but the threat of gang retaliation has created an almost impenetrable code of silence. Many of the guns police seize belong to repeat offenders, who may be back on the street in days.

St. Sabina has tried to break through, handing out $5,000 rewards 28 times in the last decade or so to help solve murders. The church is offering another to help find the killer of 21-year-old Oceanea Jones, who was with her boyfriend in July when they were chased by a group of men. She was shot in the back; he suffered minor injuries. “SPEAK UP FOR ME!” beseeches a poster on a church window featuring Jones’ hopeful smile.

For Pfleger, solving murders like this and seizing guns don’t address the real problem.

“Until we deal with easy access, they can pick up another 1,000 and another 1,000,” says the priest, who decades ago lost his foster son in gang crossfire. “It’s like water pouring on the floor and you keep mopping it up, but nobody’s shut off the faucet.”

Chicago police regularly recover more illegal firearms than officials in larger New York and Los Angeles. Last year, the citywide haul was 7,932 firearms. The 2018 tally exceeds 8,300, and police say it could surpass 10,000 by year’s end.

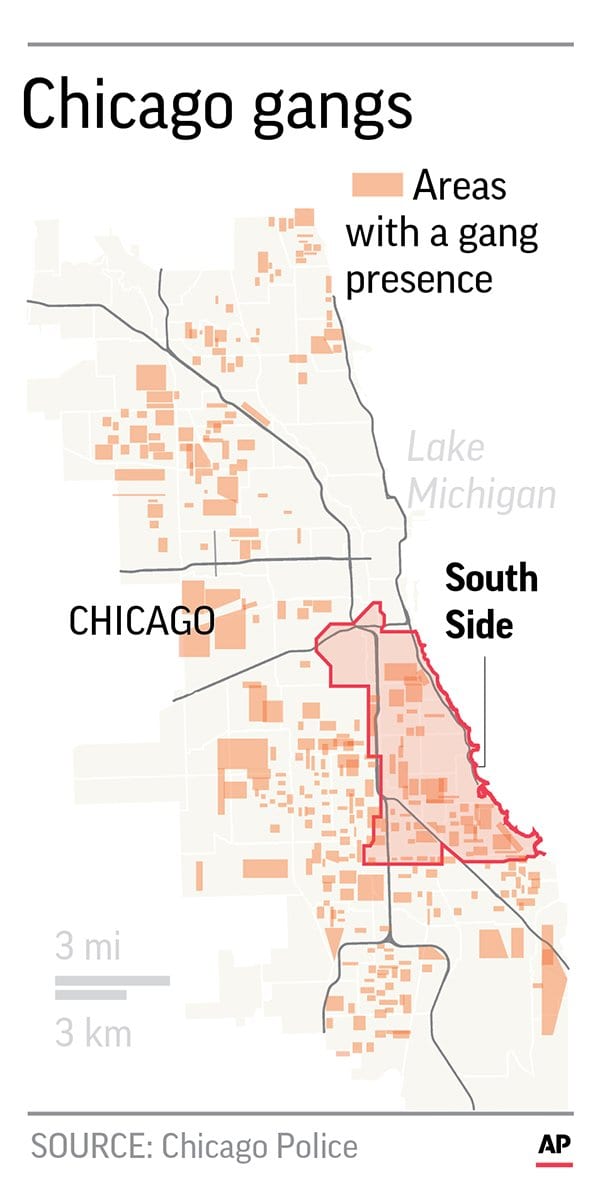

Police seize an illegal weapon about once every hour, most connected to gangs on the South and West sides. Authorities cite two reasons for the heavy gun traffic: Penalties for carrying these firearms aren’t considered a deterrent and, according to police spokesman Anthony Guglielmi, suspects tell officers they “would rather be caught by police with a gun … than caught by a rival gang without one.”

The department’s 6th District, one of 22 in all, leads the city in guns recovered, accounting for almost 15 percent so far in 2018. District Commander William Bradley sees progress in those numbers, measuring success in the smallest increments.

“Every gun that (officers) get, I get excited about that because that’s a gun that can’t be used against them or a law-abiding citizen,” he says. “I don’t look at it as a grain of salt or a drop in the bucket.”

The 6th District is an 8-square-mile stretch of overwhelmingly black working-class neighborhoods. A densely populated area, it’s thick with apartment buildings and brick bungalows, neat lawns, a busy bus route, a business strip with mom-and-pa stores and the prestigious all-boys Leo Catholic High. Every school graduate in the last eight years has been accepted to college.

The community also bears visible signs of despair: weed-filled lots, boarded-up houses, wary fast-food workers and clerks hunkered down behind protective partitions in storefronts with thick metal security gates. Gang rivalries are fierce. On the district’s eastern edge, members of an organization called Cure Violence prowl the streets as “interrupters” to keep the peace, even if it’s something as simple as arranging safe passage for someone to go to a store in another gang’s territory.

“These guys are living in their own little world of survival,” says Demeatreas Whatley, a Cure Violence supervisor. “Their enemies are not even two blocks away.”

The 6th District polices 30 different gang factions, each with anywhere from 20 to 100 members, that account for 75 percent of the area’s gun violence. The gang presence is so ordinary, the turf so defined, that everyone from pastors to grade-schoolers can tell you, for instance, which streets are controlled by the Killer Ward faction and which are run by the G-Ville faction of the Gangster Disciples.

Tracking gang guns is especially difficult because they move from one faction to another, and when police finally seize them, they’re rarely in the hands of the purchaser. “Gangs use guns like timeshares,” says Andrew Papachristos, a sociology professor at Northwestern University. “They stay in circulation.”

Once guns move from the legal to the illegal market, they can bounce around the city with no rhyme or reason, says Celinez Nunez, special agent in charge of the Chicago office of the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. She says one gun now being investigated has been used in more than 30 crimes, including homicides and assaults.

Last year, the ATF formed the Chicago Crime Gun Strike Force, a multiagency unit to combat gun crimes, and added 20 agents. The U.S. attorney’s office also has put more prosecutors on gun cases.

But the gun problem isn’t limited to gangs. A recent Urban Institute survey of young people in four neighborhoods with high levels of violence, including Auburn Gresham, found half the young men had carried a gun, though for most it wasn’t routine. Protection was the overwhelming reason.

Tommie Bosley knows that may sound strange. He runs Strong Futures, a jobs-mentoring program at St. Sabina for young adults, many with criminal pasts. His 18-year-old son, Terrell, was fatally shot in 2006 while unloading musical instruments in a church parking lot. Bosley appreciates how all-consuming fear is for law-abiding people.

“A lot of these guys are carrying weapons because they’re scared,” he says. “They feel that they cannot leave their house, go to work, whatever, unless they have a gun. They feel that at any time someone can be shooting at them and the gun — it makes them feel like they have a chance, which in my world is, ‘Are you kidding me?’ But that is the reality.”

The community has rallied to rid itself of guns. Members of New Life Covenant Church Southeast held a buy-back in coordination with police, who gave $100 gift cards to anyone who turned in a firearm. It took four hours to gather the weapons as the line snaked around the block.

At day’s end, 292 handguns and 132 rifles were out of circulation, but the event didn’t soothe the frayed nerves of some congregation members.

“There’s a constant crisis state of mind,” says Shammrie Brown, the church’s community relations manager. “Elders who are supposed to have some level of peace are traumatized to the point where they’re rushing to get home before it’s night. … There’s anxiety about going to the grocer, anxiety to go inside the church. … They want security at the park. … They want surveillance for every move that they make.”

As the church prepares to move into a new building, one looming question is whether to include a permanent metal detector.

Three miles west at St. Sabina Church, from a basement room one floor below a mural of a black Jesus beckoning with outstretched hands, Lamar Johnson is trying to shepherd the next generation of his community to speak out against gun violence.

Johnson, 28, is a counselor for B.R.A.V.E. Youth Leaders, training kids as young as 6 on how to be social justice activists. At one recent gathering of 10- to 12-year-olds, he listened as the children talked about hearing gunshots while walking to school or having to hit the ground to avoid an errant bullet while shopping with their parents.

“They talked about it as if it were an everyday thing, which it is,” Johnson says. “It makes them numb, but if something happens to you over and over, eventually you adjust.”

Johnson warns that seizing guns alone won’t transform a community long victimized by segregation and neglect.

“If you’re taking guns off the street, what are you putting in those communities for those young people who use guns? What resources are you adding? We need everything. Businesses. Jobs. Schools. This isn’t something that just started in 2018. It’s happened over decades.”

Carlos Nelson, director of the Greater Auburn-Gresham Development Corporation, is just as frustrated at the dearth of so much that would improve the community. He ticks off some of the businesses and services in the area: Currency exchanges. Quick loan shops. Dialysis and methadone clinics.

“The businesses that you would find in an area with a good quality of life, you would be hard-pressed to find them here,” he says. “The investment has not been made in our community to build the economic base. … It is being made to police the community and to deal with issues like taking the guns off the street.”

That singular focus has repercussions.

In September, Nelson was planning the 79th Street Renaissance Festival — a peaceful event for 13 years — when a Ferris wheel operator returned the group’s check, citing the violence. Though Nelson calls that “ridiculous,” he knows gun statistics that sound “like the Wild West” have taken their toll.

The community, in which 60 percent of residents are homeowners, has shrunk from about 60,000 to about 47,000 over the last 15 or so years.

“We don’t want this violence,” Nelson says. “We have a choice. The choice for many is to move out.”

Veronica Parker has remained, even though her 27-year-old son, Korey, was fatally shot around the corner from her house on July 4, 2012. She believes he was selling marijuana and might have been targeted in a turf battle.

In September, police tape cordoned off Parker’s street as officers investigated another killing. Cornelius Jackson had turned his life around, completing the Strong Futures program after a five-year prison stint for gun possession. He was newly married, working and had moved from his old neighborhood, which he described in a promotional video as a place that resulted in jail or death. On a return visit to Auburn Gresham, a gunman stepped from a car and shot the 29-year-old in the head.

Both shootings remain unsolved, one of the more unsettling realities in places awash in guns. Bradley, who grew up in the area, understands how fear of gangs stifles cooperation. Chicago’s murder clearance rate in the last two years was 38 percent.

“If I come forward … and nothing is done, I put myself and my family at risk,” he says. “If these witnesses to crimes don’t say anything, we can’t do anything. I don’t have a real solution.”

Parker is a member of Purpose Over Pain, a support group for parents who’ve lost children to guns. They’re determined to find ways to curb the violence but, she concedes, “there’s a void in my life that will never be filled.”

Parker last spoke with the detective investigating her son’s case three years ago. “It’s like they just forgot him,” she says. When she’s out in the community these days, she’s dismayed by what she sometimes hears.

“Young guys (are) saying they’ve made it to age 30 without getting shot or killed, and they think they’ve accomplished something. It’s heartbreaking.”

Parker applauds police for going after guns but harbors no illusions.

“If they get 100 or 1,000, others are still out there. As soon as the police pick up the guns, they’ll just go and get them somewhere else.”

By December, the 6th District had recovered more than 1,200 guns.