New research from public records and congregation and diocesan archives has found that six congregations of the Sisters of Charity Federation have predecessors who owned slaves.

In a Feb. 7 letter to the more than 2,000 sisters whose congregations are members of the Sisters of Charity Federation, federation leaders said the research shows that the two original congregations of Charity sisters in the United States owned slaves before slavery was outlawed in 1865.

Six of the 13 congregations in the federation trace their roots to the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph’s, founded by St. Elizabeth Ann Seton in Emmitsburg, Maryland, in 1809. According to the research, led by the archivist for the Daughters of Charity in Emmitsburg, the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph’s and the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul owned and sold enslaved people in Maryland and benefited from slave labor in New Orleans and St. Louis.

Sister Catherine Mary Norris, a Daughter of Charity, who chairs the federation’s board of directors, told Global Sisters Report the involvement with slavery was previously unknown but shouldn’t have been.

“We knew we had worked in Southern states … and Maryland was probably one of the worst slave states in the country, so it shouldn’t have been a surprise,” Norris said. “We need to know our own history. We need to own it and be willing to acknowledge it and move on.”

The research began in 2019, spurred in part by historian Shannen Dee Williams’ address to the 2016 assembly of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious and that year’s conference resolution, which committed LCWR members to “examine the root causes of injustice, particularly racism and our own complicity as congregations.”

Williams’ book — Subversive Habits: Black Catholic Nuns in the Long African American Freedom Struggle — is set for release May 6.

Also in 2019, The New York Times published an analysis examining slave ownership by sisters.

“Historians say that nearly all of the orders of Catholic sisters established by the late 1820s owned slaves,” it noted, and cited a Sister of Charity superior in Emmitsburg who directed the sale of their “yellow boys.”

“Anybody who knows the history of the Catholic Church in the 1800s and before could not say that there wasn’t at least the possibility” of slave ownership by the sisters, said Belinda Davis, spokesperson for the Daughters of Charity of the Province of St. Louise. “There were already several published articles about people in the church and their involvement in slavery.”

The Sisters of Charity Federation’s letter, signed by Sister Norris and federation executive director Sister Grace Hartzog, a Sister of Charity of Seton Hill, asked for forgiveness.

It also noted: “While the institution of slavery and the exploitation of enslaved people was deeply engrained in the society and economy of the 19th century, this shameful historical reality does not diminish our profound regret and dismay today.”

The letter also stated the importance of knowing this troubling history.

“Slavery is an indelible stain on our nation’s history and conscience that has permanent and painful repercussions, most profoundly for Black Americans,” it stated. “We believe that only by shining a light on difficult, shared truths can we truly move forward together in unity.”

The research found that the two Maryland congregations owned at least three enslaved people, sold slaves on at least two occasions and benefited from slave labor.

In New Orleans, the Sisters of Charity benefited from the labor of people enslaved by the state of Louisiana during the sisters’ work at Charity Hospital, and there is evidence the Sisters of Charity were involved in decisions related to the sale of slaves.

In St. Louis, researchers found documentation that the Sisters of Charity benefited from slave labor in their work at Mullanphy Hospital.

Though only the six congregations in the federation that came from the congregation Mother Seton founded were involved in the research, all 13 federation members signed the letter as a show of solidarity.

“Obviously, you cannot change the past, and they know that, but they want to be honest and transparent with everything they know,” said Susan Oxley, spokesperson for the federation. “They want to do the right thing.”

The research also examined whether Mother Seton owned slaves herself but found no evidence of it.

When she was 3, her grandfather left her an enslaved man in his will, but “there is no further record of this enslaved man’s fate.” The letter cited a book by historian Catherine O’Donnell, who said she believes he escaped during the Revolutionary War, which ended when Elizabeth Seton was 7.

One of the schools Mother Seton founded “knowingly accepted payment for tuition that used proceeds from the sale of an enslaved person” during Mother Seton’s lifetime, the letter said, and also accepted payment in the form of slave labor, according to O’Donnell.

Currently, plans are being made for a monument to the enslaved people on the Daughters of Charity campus in Emmitsburg, about 60 miles northwest of Baltimore.

“We will explore additional, meaningful, actions that will contribute to the work that must be done to bring about significant change,” the letter said. “We pledge to move further into the work of racial equity; to remember and learn from our past; and to confront systemic racism through our words and actions.”

Norris said there had been no pushback from sisters who want to forget the past and move on. The letter explained why that is not an option.

“The damage done by slavery is enduring,” it said. “The passage of time does not diminish the injustices perpetrated against enslaved individuals and families or the persistent racism, discrimination, injustice and inequity that demand continued action by all of us.”

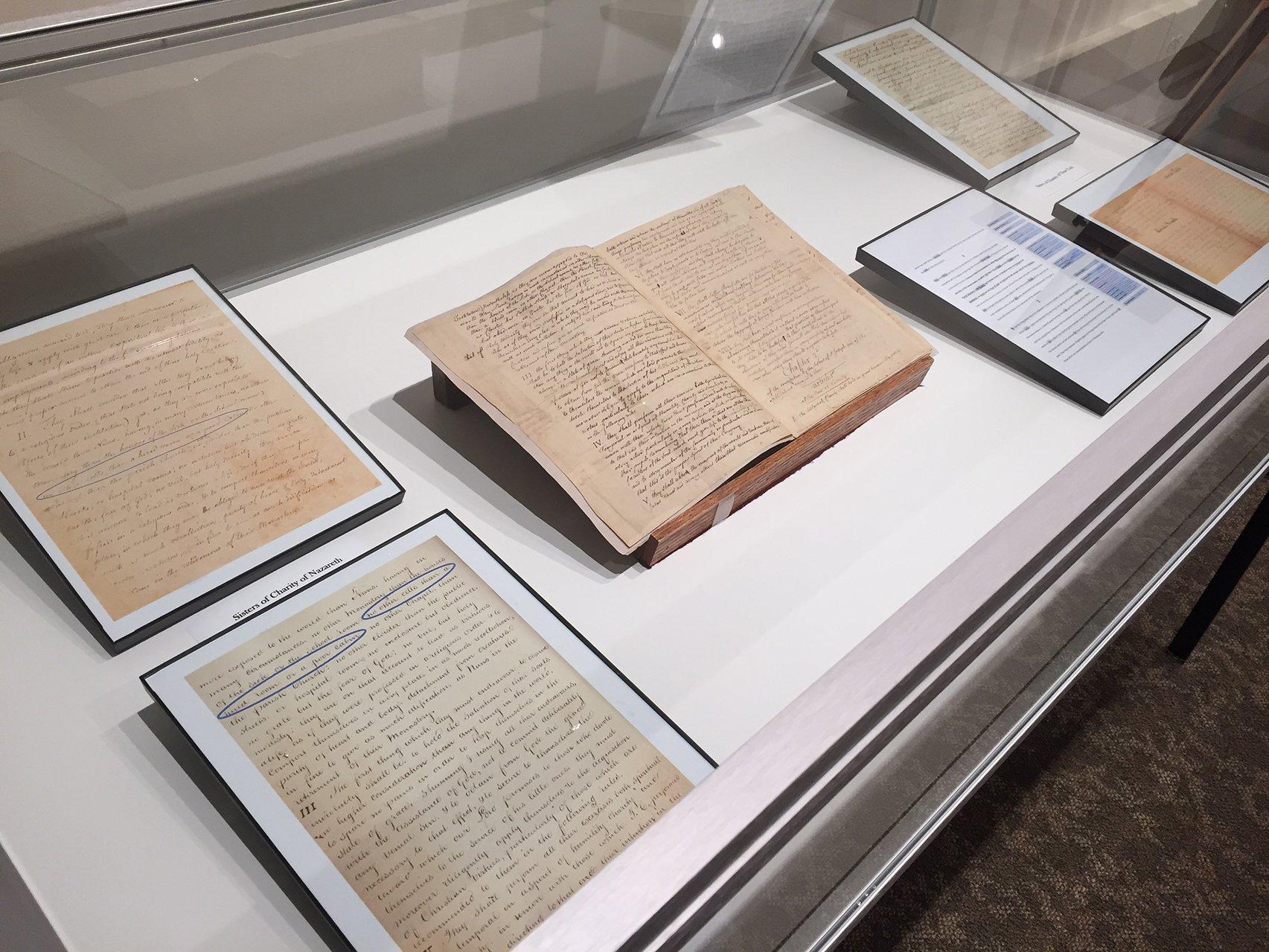

Norris said the research will continue, and the federation is exploring the idea of hiring a historian who can better interpret the findings and put them in context. They also hope to digitize records so people doing genealogical research, especially descendants of the enslaved people, can have access to them.

“None of us can change history. It’s how we can learn from it and go from there,” she said. “There’s been a lot of broken trust that needs to be rebuilt. We have to start someplace, and this is one small place we can start.”

Stockman is a national correspondent for Global Sisters Report.