JEFFERSON CITY, Missouri — “God forgive me, I hope he’s in heaven,” Benedictine Father Kenneth Reichert said about the man who entered Conception Abbey 20 years ago, pointed a semi-automatic MAK-90 rifle at him and fired twice.

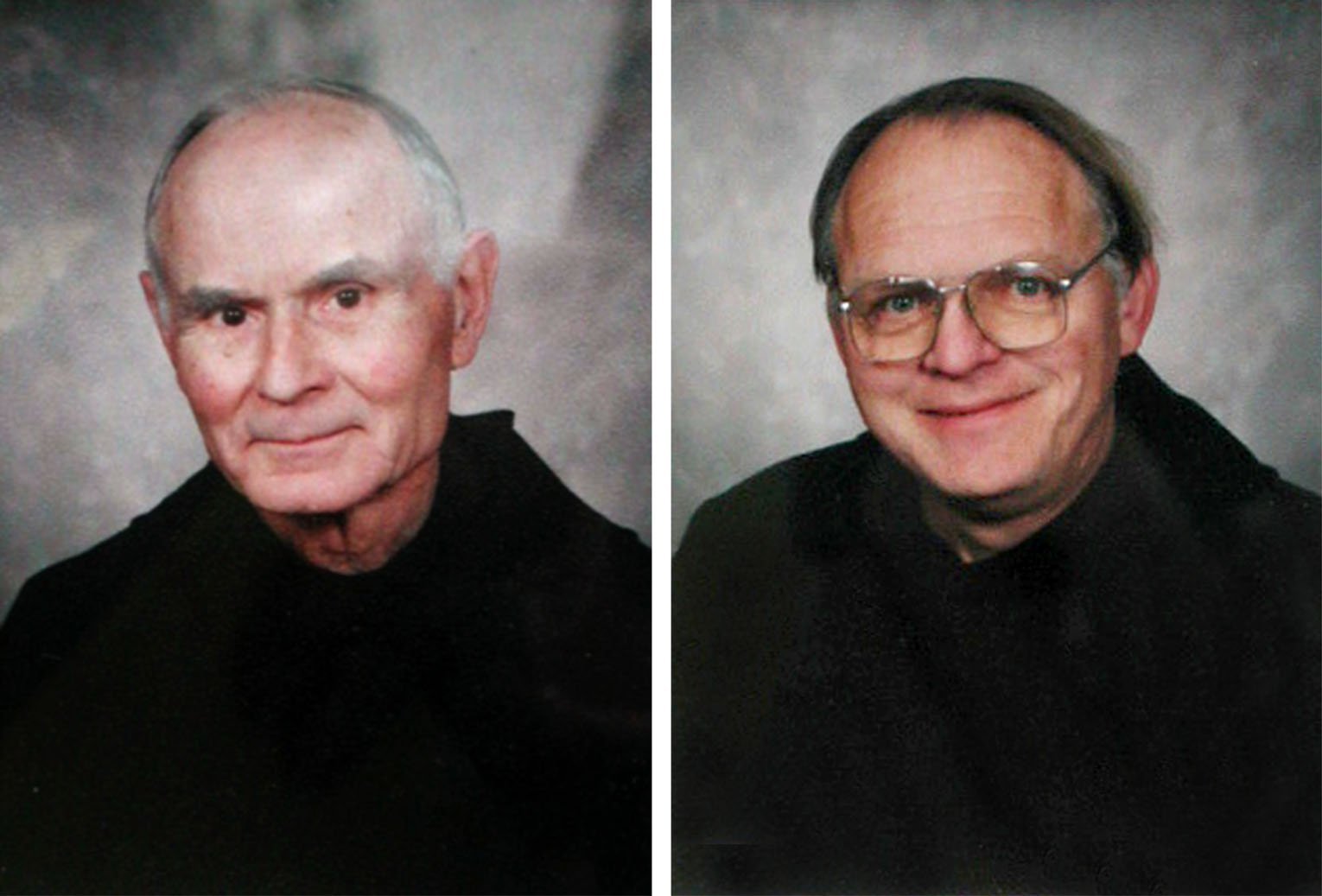

Two Benedictine monks were killed that day, Father Philip Schuster and Brother Damian Larson, and Reichert and Benedictine Father Norbert Schappler were critically injured before the shooter entered the monastery’s great basilica and turned the weapon on himself.

Reichert expected to die in a puddle of his own blood, but “God never left me,” he said. “I prayed many acts of contrition, and many times (prayed), ‘God forgive me.'”

No day passes without Reichert remembering the events of that day, June 10, 2002.

Neither his body nor his mind will let him forget.

“Yet, I am grateful to be alive and to be given so many chances to repent and turn back to God since then,” he told The Catholic Missourian, newspaper of the Diocese of Jefferson City.

Conception Abbey is in the neighboring Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph, Missouri.

Reichert, a native of Brunswick, Missouri, who has been a Benedictine monk for nearly seven decades, is convinced God also remained close to the 19 children and two teachers who died in the May 24 school shooting in Uvalde, Texas.

“He never left those kids,” the priest said. “I am certain they’re now in heaven and happy with him.”

But although present, God did not stop the shooter at the monastery, 71-year-old Lloyd Robert Jeffress.

Nor did God stop any of the others who have contributed to the bone-chilling litany of mass shootings in recent weeks, the latest being the July 4 tragedy during an Independence Day parade in suburban Chicago that took at least seven lives and injured about 30 others.

“When something bad happens, we tend to want to blame somebody,” said Reichert. “Part of that can be put on God: ‘Why did God allow that?’

“Well, because God gave them free will, just as he gives it to you and me,” the priest stated. “When we’re the one who is hurt, we wonder why God didn’t step in and take away the free will of another person. But I don’t want God to take away my own free will.”

Reichert noted that doing so would remove each individual’s ability to do evil but also his or her capacity to love.

“God loves us freely and wants us to love him freely,” said Reichert. “Coerced love is not love at all. Love is freely given.”

Stunned and horrified by the dreary drumbeat of mass shootings, Reichert said he’s at a loss for answers.

“But I do believe that our nation and all of us need to grow in love,” he said.

He’s concerned about the hopelessness and lack of love and family connection many mass shooters seem to have in common.

He also suspects a pattern of “copycat” behavior when so much of the news coverage focuses on the perpetrator, rather than the victims and their families.

“If someone is angry and mixed up in the head and going through a difficult time in their life, and they hear about something like this, they see it as an opportunity to repeat the same thing,” he said.

He observed that most mass shooters wind up dying by suicide.

“That suggests to me that we’re dealing with people who are profoundly confused and can’t or don’t think through what they’re doing,” he said.

He’s also convinced that diabolical influences play a role in such calloused and deadly behavior.

“There is a devil. Evil does exist in our world, and evil works in people,” he said. “It is not just a thought. Today, it manifests itself in some individuals who put it into practice in this way.”

“One thing we can do is pray,” he added. “God is love, and we need love to replace the evil that is in our lives.”

Reichert believes it’s too simple to blame easy access to firearms.

“Guns are probably too easily available, but they’ve always been available,” he said.

His own family always had a shotgun and a rifle, which he and his siblings all learned to use as part of helping on their family farm.

“We didn’t think of shooting people and then taking our own life,” he said.

But there was never a moment in his or any of his four brothers’ lives that they didn’t know they were loved by God and by their parents.

That seems to be part of what’s missing when people set out to do great harm, the priest said. “We don’t always know what’s going on in a person’s life when they decide to go and do something like this.”

“I think all of us are seeking love in life,” he said. “We all want to be liked and loved by other people. And it seems to me that some of these people who do the shooting have felt that they were left out.

“We want love, we need love and we need to give love. And one thing that all of these shootings seem to have in common is someone who’s lacking love, who doesn’t see love, who doesn’t know love.”

Reichert said the difference between heaven and hell is the presence of God, who is love and the source of all love.

The priest spent three weeks in a hospital recovering from gunshot wounds in his lower abdomen and his leg, and he could not attend the funeral Mass for the two monks who were killed.

He only heard about the tremendous outpouring of sympathy and love that filled the monastery basilica. He also received so many visitors in the hospital during that time that the nurses finally had to ask people to leave a note for him so he could rest.

His soul will never let him forget that great experience of love.

“We who have known God’s love from birth all the way until now should approach the Lord with a spirit of gratitude,” Reichert stated.

“God loves us all, and we frequently experience that love through other people,” he said. “We have known God’s love because we have known it primarily through our family and those who are close to us.”

“And we always have to remember that we show God’s love to other people by the way we treat them, as well,” he said.

Nies is editor of The Catholic Missourian, newspaper of the Diocese of Jefferson City.