With just days left before Iowa casts the first votes in the presidential nominating contests, Republican candidates have been crisscrossing the state touting their Christian bona fides, appealing to the group of voters who could make or break several campaigns. Part of this ritual includes rattling off a list of prominent Christian leaders who have come out in support of their campaigns.

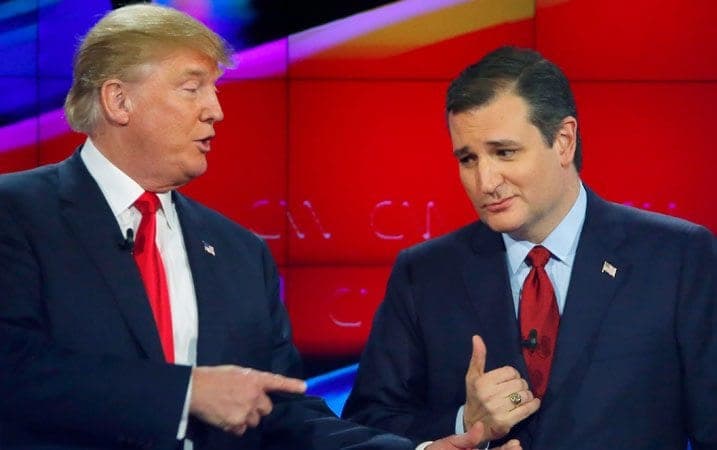

On Tuesday, for example, GOP frontrunner Donald Trump, who is polling well with Evangelical voters, bagged the endorsement of Jerry Falwell Jr., president of the influential Liberty University and son of the late Rev. Jerry Falwell.

US Sen. Ted Cruz, meanwhile, who speaks frequently of his Southern Baptist faith, has been rewarded with endorsements from Focus on the Family founder James Dobson and Tony Perkins, president of the Family Research Council.

But there are few endorsements from prominent Catholics, even though four of the remaining GOP candidates — and one Democrat, Martin O’Malley — are Roman Catholic.

A reluctance to foster divisions over politics, the Catholic vote split between the major political parties, and the fact that most Catholics don’t want their leaders to endorse candidates all serve to discourage overt political support.

The fight for Evangelical votes has been intense, and for good reason. When Iowa Republicans caucused in 2012, 57 percent of participants were Evangelical Christians. Just 18 percent of the state’s population is Catholic.

But Catholic bishops still garner media attention, and the Church’s social services infrastructure is vast. Backing from the head of a large Catholic hospital network or prestigious university, for instance, could be seen as a powerful nod of approval to Catholic voters.

Catholic leaders have so far stayed quiet during the 2016 contest, occasionally weighing in on some issues — a few bishops have criticized Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric — but in general, avoiding discussion of specific candidates.

Brian Burch, president of Catholic Vote, said lay and ordained Evangelicals often see steering fellow believers toward particular candidates as part of their job, whereas Catholic priests and even some lay heads of Catholic organizations are much more reticent to engage directly in politics.

“They don’t see a need to invite the sorts of divisions that politics often brings,” he said.

John Gehring, whose book “The Francis Effect” explores the political landscape of the US Catholic Church, agrees.

“Catholic teaching views politics and public life as essential parts of serving the common good,” he said. “But most Catholic clergy recognize that even the appearance of an endorsement undermines the Church’s ability to speak truth to power and offer a moral framework for our policy debates.”

Part of that reticence to align too closely with specific candidates could be cultural.

According to a 2014 study from the Pew Forum on Religion in Public Life, just 32 percent of Catholics believe churches should endorse religious leaders, compared to 42 percent of white Evangelicals.

Catholics also tend to be much more divided when it comes to political leanings compared to their Evangelical counterparts, perhaps making Church leaders more reluctant to be overtly political.

In the past three presidential elections, Evangelical voters favored Republican candidates over Democrats by a margin of more than 50 percentage points. In contrast, the Catholic vote split between Republican and Democratic candidates was never more than 9 percentage points.

And with that, there seems to be little appetite among Catholic clergy to endorse candidates.

In the run-up to the 2012 election, some pastors took to the pulpit to endorse candidates, flouting IRS regulations that prohibit nonprofit institutions, including churches, from partisan political activity. (Pastors and heads of nonprofits who make endorsements skirt the regulation by claiming to offer their opinion only as a personal preference.)

Of the nearly 1,500 pastors participating in “Pulpit Freedom Sunday,” NBC News found that only about 10 were Catholic priests.

Then there is the issue of ecclesial structure, which may make it more difficult for Catholic clergy to show support for specific candidates.

Evangelical pastors are free of central oversight, able to run their churches as they see fit, which may include heavy political involvement if they so desire.

Catholic bishops and priests, on the other hand, operate within a strict hierarchical model, one in which public endorsements of political candidates are discouraged.

The US Conference of Catholic Bishops released a document last March reminding Catholic dioceses and parishes that the IRS prohibits them from endorsing political candidates, and urging them to tread carefully when it comes to political activity.

Some dioceses add another layer of restrictions.

For example, Catholic dioceses in Virginia tell Church employees that they “must make clear that they are not acting as representatives of the Church or Church organizations,” if they engage in partisan political activity.

That aside, Catholics don’t stay out of the political waters entirely.

Sen. Marco Rubio announced earlier this month the creation of his “Dignity of Life Advisory Board,” which includes Helen Alvare, a professor of law at George Mason University who is also an advisor to the US Conference of Catholic Bishops.

In November, Cruz announced an endorsement from the Rev. Edward Lofton, a South Carolina Catholic priest and official in the Diocese of Charleston.

There was also the September announcement from former Florida governor Jeb Bush, which boasted of endorsements from three former US ambassadors to the Holy See.

Gehring, who is also the Catholic program director for Faith in Public Life, said some bishops and priests have long signaled support for a particular candidate more discreetly, sometimes suggesting Catholics cannot vote for a candidate who supports abortion rights.

“A vocal minority of Catholic leaders, including some priests and bishops, have not been shy about jumping into the fray of electoral politics with statements that in some cases amount to de facto endorsements,” he said, using as an example a 2012 letter from Madison Bishop Robert C. Morlino that he said subtly discouraged Catholics from voting for President Barack Obama.

At their November meeting in Baltimore, US bishops voted to re-release their Catholic voting guide, “Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship” – with few changes specific to the 2016 election.

Critics say the document continues to nudge Catholics toward GOP candidates, with the new draft re-emphasizing hot-button topics such as opposition to gay marriage and by including numerous mentions of the “intrinsic evil” of same-sex marriage as well as abortion, which the document stresses must remain top priorities for Catholic voters.

So while the nation looks to Iowa’s Evangelicals to kick-start the presidential contest, Catholic Vote’s Burch said Catholic leaders should add their voice to the political fray, because he thinks Catholic social teaching, a body of doctrine on issues such as social justice, poverty, wealth, and economics, has much to add to the conversation.

“The country is not a socialist-oriented electorate, but it’s not a Tea Party electorate either,” he said. “It’s somewhere in the middle. We think Catholic social teaching, properly applied, largely mirrors that.”

Although Catholic Vote usually backs Republican candidates — Burch said support for same-sex marriage and abortion rights usually rules out the possibility of backing Democrats — the organization has so far stayed on the sidelines. It did, however, offer a sort of anti-endorsement Wednesday, telling its half million members: “Not. Trump.“