If a sociologist from Mars were to come down to earth to study popular religion in Italy, the conclusion might easily be that the Christian “Holy Trinity” in il bel paese is not actually composed of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, but rather of God, the Virgin Mary, and Padre Pio.

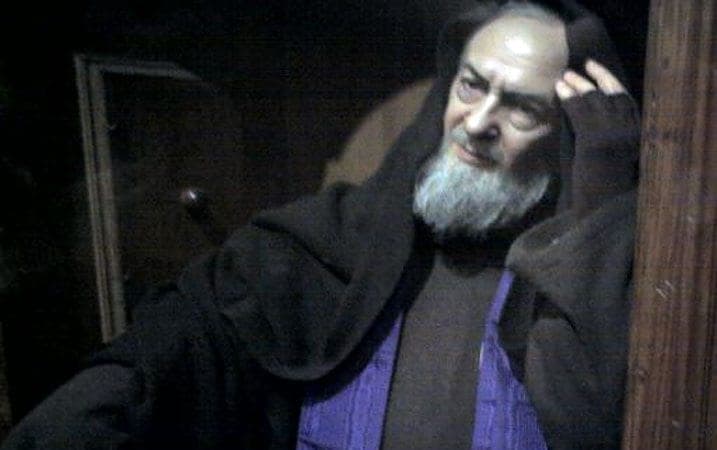

Looking around, a staggering share of restaurants, bars, taxis, and private homes up and down the country feature images of Padre Pio, the famed Capuchin stigmatic who died in 1968 and who’s now formally “St. Pio of Pietrelcina” after his canonization in 2002 under St. John Paul II.

Almost 50 years after his death, Padre Pio’s face remains easily the most recognized and cherished visage of any Italian cleric of his time. In 2001, a poll asked Italians what person or institution they would turn to in a moment of need. The No. 1 answer, dwarfing every other candidate, was Padre Pio with 53 percent.

So powerful is Padre Pio’s hold on the Italian imagination that many handicappers believe part of what made Cardinal Sean P. O’Malley of Boston a crowd favorite for pope three years ago, in the conclave that eventually produced Pope Francis, is that the American cardinal looks and sounds a great deal like his Capuchin confrere.

This week, Padre Pio takes center stage as part of Francis’ jubilee Holy Year of Mercy.

- On Wednesday, his remains, along with those of Croatian Capuchin St. Leopold Mandić, were moved from their locations in San Giovanni Rotondo and Padova, respectively, for a week-long exposition in Rome. They arrived at the basilica of St. Lawrence Outside the Walls, where a liturgy of welcome was led by the local superior of the Capuchin order, and then a Mass was celebrated by Cardinal Agostino Vallini, the pope’s vicar for Rome.

- On Thursday, leaders of the various branches of the Franciscan family will celebrate separate Masses at St. Lawrence Outside the Walls, followed by a penitential service led by Italian Archbishop Rino Fisichella, president of the Pontifical Council for Promoting New Evangelization and more or less the “director” of the pope’s jubilee. Confessions will be available throughout the day.

- On Friday, a procession will lead the relics of the two saints to St. Peter’s Basilica. The procession will depart from the parish church of San Salvatore in Lauro, just across the Tiber river from the Vatican.

- On Saturday, Pope Francis will hold a jubilee audience for members of Padre Pio prayer groups around the world, as well as employees of the Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, the massive hospital founded by Padre Pio, and members of the Italian diocese of Manfredonia – Vieste – San Giovanni Rotondo, where his principal shrine is located.

- On Feb. 9, Francis will celebrate a Mass for all the Capuchins of the world.

- On Feb. 11, the relics of Padre Pio will be moved to Pietrelcina.

At first blush, Padre Pio may seem an odd choice for a patron saint of the pope’s jubilee.

Francis, after all, is a rational Jesuit who’s famously declared that God is not “a magician, waving a magic wand.” Padre Pio, meanwhile, is associated with all sorts of miraculous phenomena that critics over the years have dismissed as smacking of medieval superstition.

They include his stigmata (the five wounds of Christ said to have appeared on his body), his ability to levitate, and a capacity to read minds. Padre Pio also supposedly could bi-locate; for most of his life he never left his friary, but he was reported in far-away places such as Genoa, Uruguay, and Milwaukee, healing and comforting. Even allied pilots during World War II reportedly saw visions of Padre Pio in the sky, credited by devotees with saving San Giovanni Rotondo from being bombed.

Then there was the strange scent of roses said to emanate from Padre Pio’s body, the so-called “odor of sanctity.”

Yet as renowned Italian Vatican writer Vittorio Messori once put it, if we decide to send Padre Pio back to the Middle Ages, then truckloads of contemporary men and women will have to go with him, because few modern saints inspire more passionate devotion.

There are many figures well-suited to serve as patron saints of the pope’s jubilee, including St. Faustina Kowalska, founder of the Divine Mercy devotion; St. Therese of Lisieux, the “Little Flower” for whom mercy was spiritually central; and Mother Teresa, an exemplar of mercy in action.

There are least four reasons why Padre Pio also belongs on that list.

Popular faith

One rock-solid spiritual conviction for Pope Francis is the belief that popular religion reveals the faith of the poor better than a whole bookshelf full of learned theological treatises.

As the archbishop of Buenos Aires, the future pope made a point of taking part in the various devotions of the groups that made up the population of the city’s villas miserias, or slums. When he played the lead role in producing a 2007 document of the Latin American bishops, he made sure it included a treatment of “how the poor meet God in shrines.”

Francis can’t help but be impressed by the fact that the champions of devotion to Padre Pio have never been sophisticates, who tend to look upon his cult with scorn. It’s always been simple people – especially the sick, the poor, the imprisoned, and the abandoned – who’ve seen in Padre Pio an icon of mercy and compassion for their suffering, as well as a powerful intercessor for healing.

The “pope of the poor,” in other words, is determined not merely to take the material needs of the poor seriously, but also their faith.

Charity

Francis has stressed that the aim of the jubilee year is not merely to foster abstract reflection on the spiritual virtue of mercy, but also to unleash concrete expressions of mercy in charity and service.

That was the point, for instance, of opening not merely holy doors in churches for the jubilee, but also of traveling across Rome to open a “holy door of charity” at a homeless shelter. It’s also why he’s performing unannounced gestures of charity throughout the year, intended to illustrate the traditional corporal works of mercy.

Looking at the way the Padre Pio devotion has developed, Francis has to be impressed with how this link between devotion and service has always been front and center.

The centerpiece is the Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, or “House for the Relief of Suffering,” a massive hospital founded in San Giovanni Rotondo in 1956 in response to the personal desire of Padre Pio. Now considered one of the most efficient and highly specialized medical facilities in Europe, the hospital counts 1,000 beds divided into 40 medical and surgical units, treating 57,000 inpatients each year from Italy and all over the world.

The original idea of the hospital was to make high-end medical care available to the area’s poor, and serving the poor remains the heart of its mission today.

“If it were possible, I would make the home of gold,” Padre Pio once said, “because the sick person is Jesus, and everything we do for the Lord is too little.” He called the poor and the sick “Twice Jesus.”

The original Casa Sollievo has inspired similar facilities around the world, such as the Casa San Pio in the diocese of Lexington, Kentucky, designed to provide medical care to poor and underserved communities of Appalachia.

Confession

Pope Francis’ passion for confession is well-known, featured in the way he has surprised ceremonial officials in the Vatican by insisting on receiving the sacrament himself before administering it during penitential rites in St. Peter’s Basilica.

That’s another point of contact with Padre Pio, who was likely the most indefatigable Catholic confessor of the 20th century.

The statistics are staggering. Early on, Padre Pio would hear confessions 15 to 19 hours every day. Later, by the 1940s and 50s, he was forced to curtail things a bit, limiting himself to eight hours a day. Still, in 1967, the year before his death, he heard the confessions of around 15,000 women and 10,000 men, for an average of 70 people every day.

Overall, during his lifetime he’s believed to have heard 5 million confessions.

Padre Pio recommended that Catholics receive the sacrament once a week, saying, “Even if a room is closed, it is necessary to dust it after a week.”

Penitents would flock to confess to Padre Pio, despite his reputation as a fairly demanding confessor. One story has it that he once refused to absolve someone, convinced that repentance was lacking, and as the person left, Padre Pio shouted: “If you go to confess to another priest to have gain absolution, you will go to hell together with him!”

“It is a tremendous responsibility to sit in the tribunal of the confessional,” Padre Pio once said. “God runs after the most stubborn souls. They cost him too much to abandon them.”

Misunderstanding

Finally, there’s another reason why Pope Francis might feel kinship with Padre Pio. The pontiff repeatedly has warned Church officials, including the potentates in the Vatican, against the risk of “small-minded rules,” instead calling them to be “ministers of mercy.”

Padre Pio knew a thing or two about the sting of “small-minded rules,” and the fact that today he’s celebrated as one of the great 20th century saints likely is seen by Francis as one of the great triumphs for mercy over judgment in recent memory.

This is a man, after all, who was investigated by the Vatican’s Holy Office, the forerunner of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, somewhere between 12 and 25 times, depending on how you count. At various times he was forbidden from saying Mass in public, from publishing, from receiving visitors, even from talking to women alone.

The whispered consensus on Padre Pio in the halls of the Vatican for a long time was that he was at best a naïve hysteric, at worst a con man.

When rumors of Padre Pio’s stigmata and other miraculous abilities began to circulate, his local bishop was skeptical. In March 1920, Pope Benedict XV sent his physician and two archbishops to investigate. When Pius XI became pope in 1922, another inquest followed, and Padre Pio was ordered not to say Mass publicly. He was to be moved to another friary, perhaps in northern Italy, maybe in Spain or America.

Some 5,000 locals, however, threatened to riot, and Rome backed down.

In 1922, a well-known Italian theologian and physician, Franciscan Rev. Agostino Gemelli, a specialist on the subject of stigmata cases, concluded that Padre Pio was a “hysteric” and the stigmata was self-induced. (Gemelli, by the way, was the founder of Rome’s Gemelli hospital, where popes now receive much of their health care.)

More investigations followed, on and off for decades. In 1960, an Italian monsignore, Carlo Maccari, began an investigation on behalf of Pope John XXIII. His 200-page report, though never published, is said to be devastatingly critical. Vatican gossip had it that the “Maccari dossier” was an insuperable obstacle to Padre Pio’s sainthood.

The final rehabilitation of Padre Pio was achieved under St. John Paul II, who traveled to confess to the Capuchin friar in 1947 and later credited him with saving a close Polish friend from cancer.

Partly on the basis of the opposition and criticism he experienced, Padre Pio wrote one of his few published works, called “The Agony of Jesus in Gethsemane.” Discipleship, he wrote, involves sharing Christ’s grief and pain. He always accepted whatever edicts came his way; one of his best-known sayings was, “The habit of asking why has ruined the world.”

For a pope who has faced no small share of blowback and resentment himself, that line probably resonates awfully well, especially in the context of a year-long reflection on mercy.