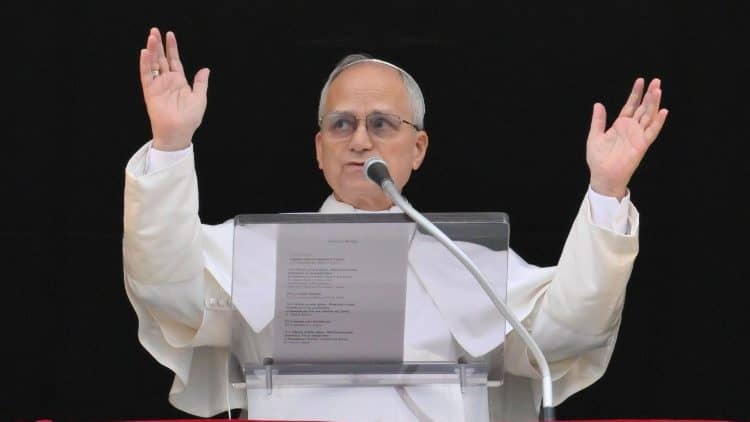

HAVANA — In an historic encounter which, in a sense, has been centuries in the making, Pope Francis and Patriarch Kirill of the Russian Orthodox Church met Friday in Havana, issuing a joint declaration pledging their churches to “walking together.”

It was the first-ever meeting between the leaders of the Catholic and Russian Orthodox churches, the two largest Christian groups on each side of the rupture between Eastern and Western Christianity conventionally dated to 1054.

“We spoke as brothers, we have the same baptism, we are both bishops,” Francis said. “We talked about our churches, agreeing that unity is built by walking together.”

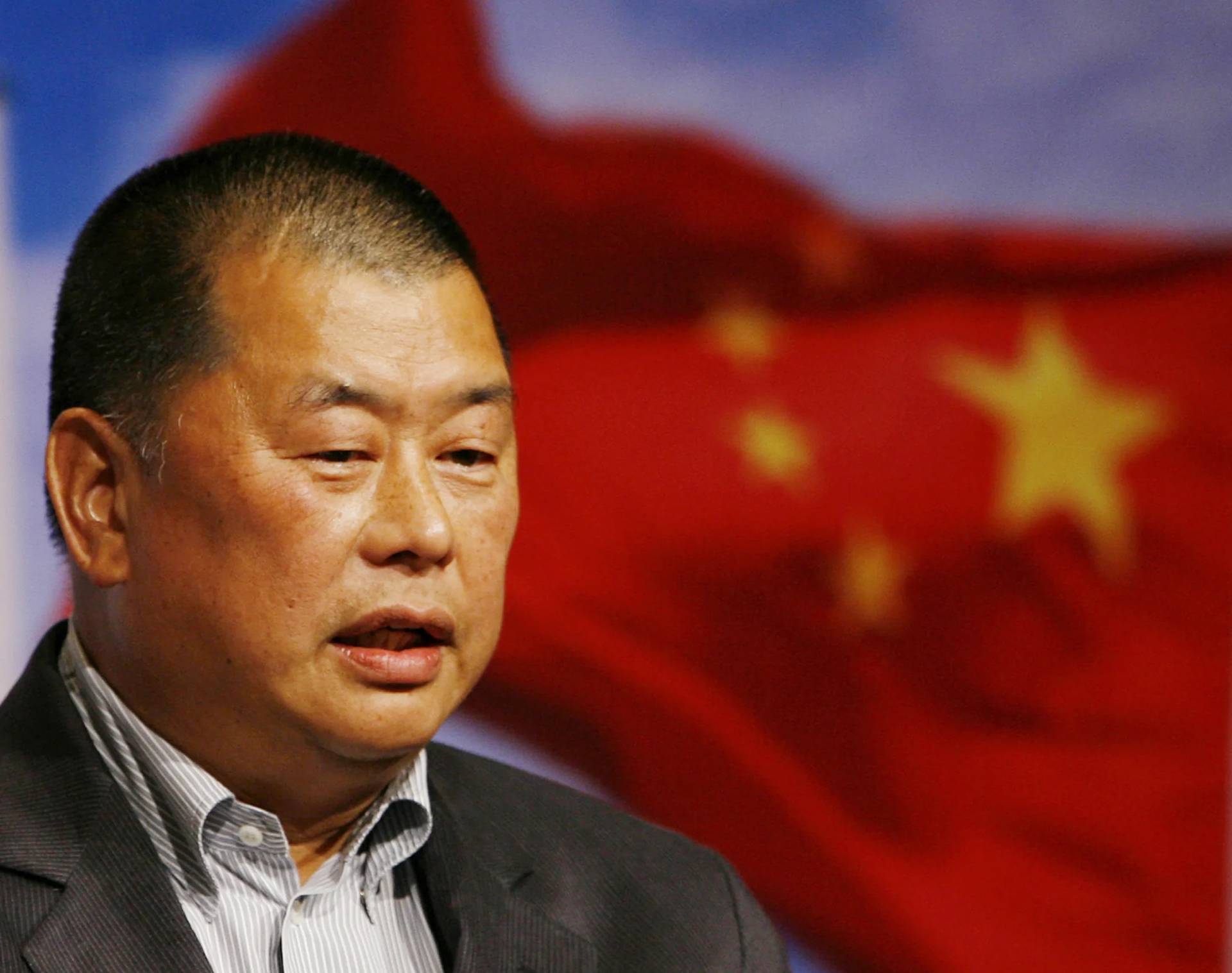

“[We met] for our churches, our people of believers, the future of Christianity and the future of human civilization,” Kirill said. “The results let me assure [you] that the two churches can cooperate to defend Christians around the world, and, with full responsibility, work together.”

Francis began his outreach even before the meeting began. Asked aboard the papal flight to Havana when he would carry the press corps to either Russia or China, the pontiff said, “Russia and China, I carry them here,” touching his heart.

Francis also tweeted on Friday that “today is a day of grace,” describing the meeting with Kirill as “a gift from God.”

Meanwhile, the Russian news agency TASS reported that Kirill told Cuban President Raul Castro earlier on Friday that he placed “great hope” in the meeting with Francis, and signs of a thaw between the two churches were seemingly already visible. On Thursday, the head of Lebanon’s Maronite Catholic Church and a representative of the Patriarchate of Moscow met in Bekerke, Lebanon, the headquarters of the Maronite leader.

Key points in the declaration signed by Francis and Kirill on Friday include:

- An acknowledgement that “we have been divided by wounds caused by old and recent conflicts, by differences inherited from our ancestors.”

- Deep concern for “Christians [who] are victims of persecution.” The two leaders said, “In many countries of the Middle East and North Africa whole families, villages and cities of our brothers and sisters in Christ are being completely exterminated. Their churches are being barbarously ravaged and looted, their sacred objects profaned, their monuments destroyed.”

- A plea for greater interreligious dialogue: “Differences in the understanding of religious truths must not impede people of different faiths to live in peace and harmony,” the two men said.

- Worry about secular hostility to religion: “We observe that the transformation of some countries into secularized societies, estranged from all reference to God and to His truth, constitutes a grave threat to religious freedom. It is a source of concern for us that there is a current curtailment of the rights of Christians, if not outright discrimination.”

- Defense of immigrants and refugees: “We cannot remain indifferent to the destinies of millions of migrants and refugees knocking on the doors of wealthy nations,” they said.

- A strong call for preserving the “natural family” based on marriage between a man and a woman, and the “right to life,” including opposition to abortion and euthanasia.

- An invitation to “prudence, social solidarity and action aimed at constructing peace” in Ukraine.

The face-to-face lasted just over two hours, and was held in Havana’s José Martí International Airport.

The emphasis on persecuted Christians in the Middle East in the declaration is especially noteworthy, as it was cited in advance of the meeting by leaders on both sides as lending special urgency to the encounter.

The Pew Forum estimates there are roughly 5.6 million Catholics and 5.5 million Orthodox in the Middle East and North Africa, each between 1 and 2 percent of the region’s population.

“The situation shaping up today in the Middle East, in North and Central Africa, and in some other regions where extremists are carrying out a genuine genocide of the Christian population, demands urgent measures and even closer cooperation,” said Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev of the Russian Orthodox Church, ahead of the meeting.

Historically, Russia has seen itself as the patron and protector of Middle Eastern Christians, especially the Orthodox. Francis has denounced the threats faced by Christians in places such as Iraq and Syria repeatedly, saying the fact that various Christian denominations are suffering together creates an “ecumenism of blood.”

Although efforts to put such a pope/Russian patriarch summit together have been underway for decades, announcement of Friday’s meeting came just one week ago in a joint statement from the Vatican and the Patriarchate of Moscow. It took advantage of the fact that Kirill was already scheduled to be in Cuba at the same time Francis would be en route to Mexico, making it feasible for the two men to intersect.

Observers say the decision by Francis to stop in Havana was also intended as a sign of graciousness, since many Russians still think of Cuba as their “home turf” in the Western hemisphere.

Popes have been meeting Orthodox leaders for decades, reaching back to the first such modern encounter between Pope Paul IV and the Patriarch of Constantinople, Athenagoras I, in Jerusalem in 1964.

The Russian Orthodox Church, however, claims roughly two-thirds of the 225 million Orthodox Christians in the world, and it has long taken a wary view of a meeting between its spiritual leader and a pope, the vestige of suspicions that Catholics want to convert Orthodox.

St. John Paul II, the first Slavic pope in history, dreamed of reuniting Eastern and Western Christianity, and for the better part of a quarter-century during the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, he voiced a desire to either visit Russia or to meet the patriarch of Moscow at a neutral site.

For reasons both theological and political, such a meeting never occurred.

Despite the historic nature of Friday’s meeting, few ecumenical experts believe it will lead to the swift restoration of full unity between Catholicism and Russian Orthodoxy.

Even the run-up brought reminders of the lingering theological and political divides.

On Feb. 5, Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev of the Russian Orthodox Church told reporters that the meeting would take place “despite the problem of the uniates,” a reference to the 22 Eastern churches in communion with Rome, which some Orthodox leaders regard as “Trojan horses” designed to peel away Orthodox faithful.

Hilarion also took pains to insist there would be no joint prayer between the pope and patriarch, noting that the meeting would take place not in a church, but an airport departure lounge.

“There are certain very conservative groups in Russian Orthodoxy that still retain a negative view of the sacramental validity of other churches, including ours,” said the Rev. Robert Taft, an American Jesuit who taught for decades at Rome’s Pontifical Oriental Institute and is considered one of Catholicism’s foremost experts on Orthodox worship.

Given the centuries of bad blood – not to mention contemporary disputes over matters such as Russia’s incursion into eastern Ukraine, which has been supported by Russian Orthodox clergy but criticized by Francis – some wonder how Friday’s meeting was possible at all.

Taft told Crux he believes both Francis’ personality and his theological vision helped make it happen.

“I think the main reason is that we’re dealing with a pope who’s just so entirely different,” Taft said.

“Remember when he said, ‘Who am I to judge’?” Taft asked. “The papacy has made a business of judging everybody on the face of the earth they could get their hands on, and here we have somebody who changes the paradigm in a flash.”

“All this reduces the anger, or fear, that the Orthodox feel in viewing Rome’s approach to them,” he said. “Russia is coming to understand that the Catholic Church sees them as a sister church, not as someone who separated from the only real Church.”

“It’s a new ball game,” Taft said.

On the other hand, not quite everyone was prepared to celebrate Friday’s meeting – especially in Ukraine, home to the 5-million-strong Greek Catholic Church, which has long been ground zero for tensions between Catholics and Russian Orthodox.

While welcoming the meeting and praying for its “spiritual fruit,” Bishop Borys Gudziak of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church warned in a statement issued two days beforehand that it should not be “hyperbolized.”

In part, Gudziak argued, that’s because the Russian Orthodox Church is carrying significant baggage.

“In the Putin years, the leadership of the Russian Orthodox Church, increasingly wedded to state power, has sacrificed its freedom and undermined its prophetic vocation while receiving lucrative government support,” he said.

Gudziak also implied that Moscow has political motives within the Orthodox world to exploit a platform with the pope.

“The Russian Orthodox Church presents itself as the biggest Orthodox church, but approximately half of the flock it claims is in Ukraine,” he said. “Ukrainian Orthodox are expressing their desire for independence from Moscow, from whence war is being waged against them.”

“[Independence] is something both Putin and Kirill are striving to prevent at all costs,” Gudziak said. “The asymmetry of the encounter between pope and patriarch — who they represent, and what they stand for — needs to be understood in order to avoid misconstruing the nature and impact of the Havana rendezvous.”

In an essay for Crux on Thursday, another Greek Catholic cleric, the Rev. Andriy Chirovsky of Ottowa, expressed similar concern that both Putin and the patriarch might seek to turn the tête-à-tête with the pope into a PR coup.

“I don’t think Pope Francis will allow himself to be hoodwinked or outmaneuvered,” Chirovsky wrote. “But my confidence in the Vatican’s ability to outdo the Kremlin’s propaganda machine is much shakier.”

Whatever the challenges, Taft says the Catholic Church benefits by pursuing closer ties.

“What the Catholic Church gains is a more honest view of itself, and of its place in the world,” he said.

“It’s not true that at the beginning we had one Church centered in Rome, and then for various historical reasons certain groups broke off,” he said. “It’s just the opposite. At the beginning we had various churches, as Christianity developed here and there and someplace else, and gradually different units began to be formed.”

“That’s the reality,” Taft said, “and we have to accept it.”