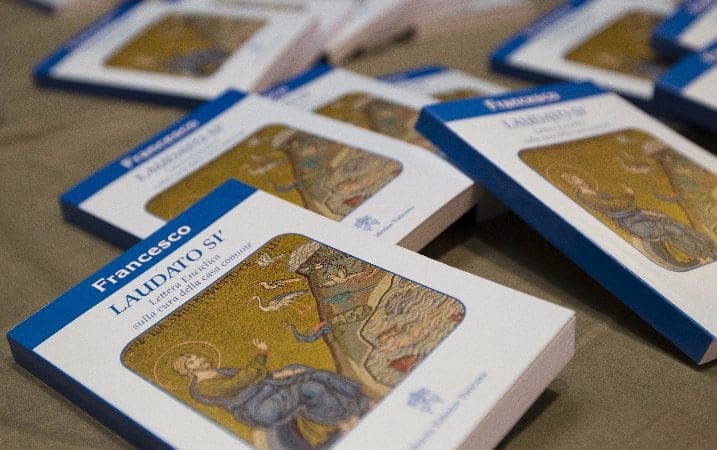

Just as we were last year around this time, once again we’re currently awaiting the release of a major papal document. Back then it was Francis’ encyclical letter on the environment, Laudato Si’; now it’s his apostolic exhortation on the family, Amoris Laetitia, scheduled for presentation on Friday.

There’s no way of knowing if history will repeat itself, but last time the text of the document leaked and was published several days before the official release date by an Italian news outlet, and it’s certainly possible the same thing could happen again.

If it does, outraged Vatican spokesmen likely will accuse whoever does it of “violating the embargo,” and that line will be widely echoed. In the spirit of trying to defuse the bomb before it goes off, here’s a brief refresher about what the word “embargo” actually means in journalistic practice.

First, a stipulation: We are not discussing a Catholic moral perspective on whether it’s okay to publish a papal text before the pope himself wants it out. Many Catholics would never dream of doing so, feeling themselves under a moral and religious obligation not to, and that’s a perfectly honorable position.

Here, however, we’re discussing what the term means to journalists striving to abide by the accepted ethical standards of the profession. “Embargo” in this context is, after all, a journalistic concept, and it’s important to be clear about how it’s commonly understood.

In a nutshell, for journalists the question of whether there’s any embargo on information arises entirely from the circumstances under which it’s obtained.

For instance, if you cover the White House and the press office gives you a copy of a presidential speech a few hours in advance, so your story can be ready to go as soon as it’s over, but on the condition that you wait to publish until the president is finished speaking, then you are ethically obliged to do so.

However, if someone else with access to it gives the speech to you and says you can use it immediately, then you have no obligation to wait. You might want to assess what his or her motives were, and whether you’re being used, but that has nothing to do with an embargo.

In other words, there’s only an embargo if your source says there is. Neither the Vatican nor anyone else has the authority to bind you to an embargo if they’re not the ones who gave you the information in the first place.

(I’m using the term “the Vatican” here in the corporate sense. Of course, when a papal text gets out in advance it’s almost always someone in or around the Vatican who passed it on, but they were not acting in an official capacity.)

The Laudato Si’ case is instructive. Italian journalist Sandro Magister and his publication, l’Espresso, were accused of violating the embargo when they published the text three days before it was released by the Vatican, and for a time Magister’s Vatican press credentials were yanked.

In reality, it was impossible for them to have violated any official Vatican restriction, because the Vatican Press Office did not release the text to journalists under embargo until 48 hours after l’Espresso published – which means, of course, l’Espresso got it through other channels.

We have no way of knowing if the source who passed the information imposed any restrictions in terms of when it could be used, but if l’Espresso and Magister violated anyone’s embargo, it certainly couldn’t have been the Vatican’s.

The Vatican obviously has the right to ask people not to publish anything before the pope is ready, but that’s all it is, a request, and from a strictly journalistic point of view there’s no obligation attached.

Of course, there are many people who find the idea of jumping the gun on an important document unhelpful. One can also understand why the Vatican, reeling from not one but two major leaks scandals, is sensitive these days to controlling the information flow.

If you are among those who believe it would be better for journalists to wait until the pope says “go” – either out of respect, or to avoid confusion, or for whatever other reason – by all means, make the argument.

Just don’t drag the term “embargo” into it, because if an embargo doesn’t exist in a given set of circumstances, then it can’t be broken.