During the late John Paul II years, one constant bit of subtext on the Vatican beat was the pope’s health and his physical capacity to lead. I used to joke that my definition of bliss would be never having to go on TV or radio again and start by saying, “Well, I’m not a doctor, but …”

As part of that chatter, anyone with even a remote connection to the Vatican was asked over and over again, “Will the pope resign?” Everyone had their own answer, but I was fairly confident John Paul would never go that route, and when pressed as to why, I would tell people I could explain it in one word.

That word was, “Fatima.”

St. John Paul II, let us remember, once dreamt of being a Discalced Carmelite priest; the story goes that the only reason he didn’t was because the Carmelite seminary in Czerna, Poland, at the time wasn’t accepting new novices due to the war.

The young Karol Wojtyla was enchanted by the works of St. John of the Cross, and would later write his doctoral thesis on the great Carmelite saint.

The fascination was part of a strong mystical streak in the Polish pontiff, which also showed up in his deep conviction it was no accident that Sister Faustina Kowalska and her message of divine mercy came along in Poland between the two world wars, arguably the least merciful chapter of that country’s long and painful history.

John Paul always saw the world, including the vicissitudes of his own life, as part of a vast cosmic drama, a struggle between good and evil, and was convinced that terrestrial explanations of the ups and downs he encountered never exhausted the possibilities.

All of which brings us to May 13, 1981, the date of the assassination attempt against John Paul II in St. Peter’s Square, which was also the feast day of Our Lady of Fatima.

As a devout Polish Catholic growing up in the 1920s and 30s, Karol Wojtyla was obviously well aware of the growing global devotion to Our Lady of Fatima and the messages she was believed to have delivered to three shepherd children. Later, he would have been captivated by their seeming relevance for Poland’s situation under Soviet rule.

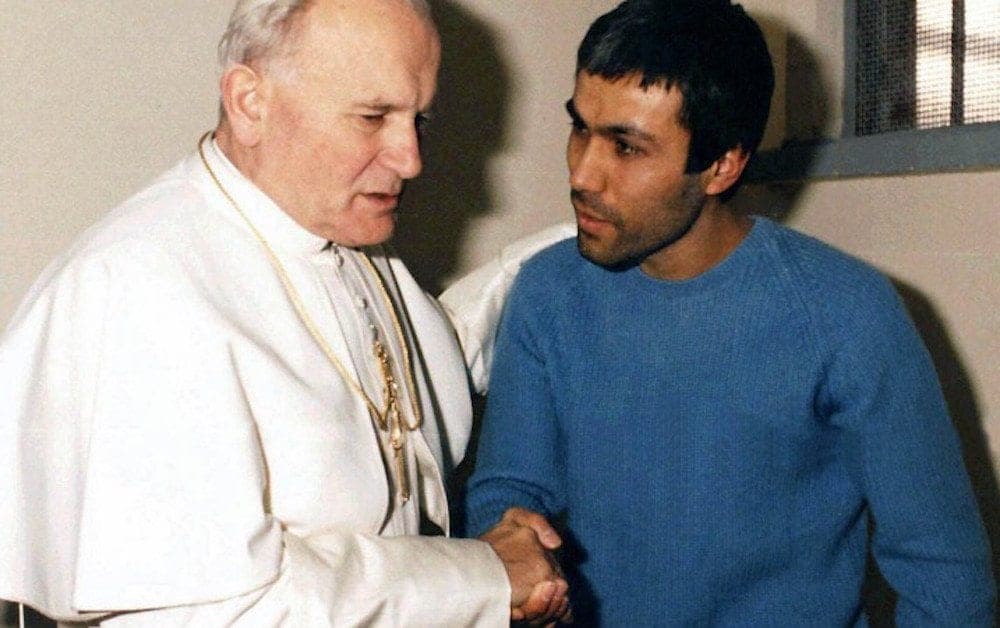

As is well known, Turkish gunman Mehmet Ali Agca fired on the pope that day at point-blank range, and he knew what he was doing – two years before, he had shot to death a Turkish journalist and human rights activist named Abdi İpekçi.

Yet the two bullets Agca fired at the pope somehow went wide of their targets, one grazing off John Paul’s elbow and the other penetrating his abdomen but narrowly missing a major artery.

To John Paul II, it was no mystery at all why he survived: the intercession of Our Lady of Fatima.

On the anniversary of the assassination attempt, John Paul II traveled to the shrine of Fatima in Portugal to give thanks to Mary for saving his life, placing the bullet doctors had removed from his body in the crown of the Virgin’s statue, where it remains to this day.

How does all this connect to the question of whether John Paul II might have resigned?

Consider the worldview at work here: John Paul II was profoundly convinced that on May 13, 1981, the Virgin Mary altered the flight path of a bullet in order to keep him alive and, in so doing, to preserve his papacy.

If you genuinely believe that Mary interceded with God in order to suspend the laws of physics to keep you in office, then you never just wake up one morning and decide you’ve had enough.

Recall that John Paul II, even before the assassination attempt, regarded his papacy as belonging to Mary, not to him, as expressed in his motto Totus Tuus, “Entirely Yours,” a line drawn from the spiritual works of Saint Louis de Montfort.

If ever the pontiff would have concluded that Mary had put an exclamation point on her rights of ownership, the day of the assassination attempt certainly was it.

In other words, John Paul II simply did not believe it was up to him to decide when it was over.

One can, of course, question the impact of that conviction. It’s worth remembering that in a 2010 interview with Peter Seewald, Pope Benedict XVI said that under certain circumstances, a pope would have not only the right but the duty to resign.

Seewald didn’t ask the obvious follow-up question, which is whether Benedict, despite his transparent love and admiration for John Paul, thought his predecessor’s long twilight was a case in point. In any event, it’s a legitimate topic of conversation.

On the other hand, defenders of John Paul’s decision to stick it out argue that he offered a precious counter-witness in a world that tends to worship at the altars of youth, beauty and productivity, that you don’t have to be any of those things to be valuable.

I once asked Jean Vanier, founder of the L’Arche community serving disabled persons, what he made of the pope’s growing “disability,” and he replied that in his opinion, “John Paul has never been more beautiful.”

In any event, John Paul’s relentless faith in Our Lady of Fatima makes one thing clear.

Whatever else they are, popes are true believers, and it’s always a mistake to discount the role of the supernatural and the mystical in shaping their psychology.