World Youth Day is sort of the Olympic Games of the Catholic Church, by far the largest regular global gathering of its kind. Charmingly, despite its name, “World Youth Day” is actually a week-long event, and routinely draws crowds in the millions.

The 2016 edition is set for Krakow, Poland, in July, and officially speaking, it already has a snazzy official anthem called “Blest Are They with Mercy!”, by Polish composer Jakub Blycharz.

For the host nation, however, there’s another ballad one can imagine in the background all week: The 1969 classic “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” by the Rolling Stones, the payoff line from which is, “but if you try sometimes, you just might find, you get what you need.”

It’s apt because Polish Catholics probably aren’t going to be welcoming the pope they really want, but given their current social and political situation, they may be getting exactly the one they need.

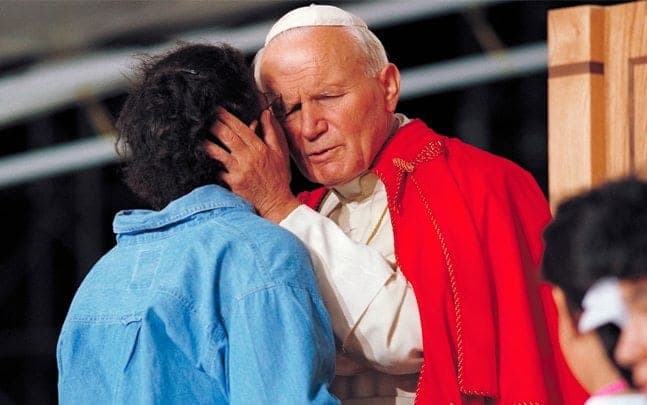

In their heart of hearts, many Poles undoubtedly would prefer to be embracing John Paul II, now St. John Paul, their native son and longtime de facto uncrowned king. During the waning years of his papacy, John Paul made a string of homecomings to Poland, each of which was labeled in the media as his “last,” and millions of Poles probably would give almost anything to be able to do it one more time.

Despite his absence, this World Youth Day nevertheless shapes up as a massive John Paul II jamboree. It’s the first time since his death the festival created by the Polish pope has been celebrated in his native country, and his image and teaching will be ubiquitous.

St. John Paul II and St. Faustina Kowalka, founder of the Divine Mercy devotion, are the official co-patrons, and the late pope’s voice likely will be the event’s soundtrack. John Paul’s legacy, especially his historic role in helping liberate Poland and all of Eastern Europe from Communism, will fill the air.

As much as it wants to celebrate its past, however, Polish Catholicism won’t be able to ignore entirely the perils of its present, and that’s where Francis comes into the picture.

In many ways, the Polish Church remains comparatively healthy, certainly by the standards of other European societies. Although Mass attendance rates are in decline, they still hover just under 40 percent, and churches are routinely packed.

Polish missionary priests are increasingly following their people emigrating to various parts of the world, with vibrant Polish diaspora communities now flourishing in places such as England and Ireland.

If there is to be a revitalization of the faith on the Old Continent, Poland will have to be one of its nerve centers and driving forces.

Yet there are also signs of underlying weakness, including declines in seminary enrollment and recruitment to religious orders, and mounting frustration with perceived clericalism and indifference to laity. One recent study, for example, found that few of Poland’s more than 10,000 Catholic parishes actually have the pastoral and finance councils involving laity anticipated by canon law.

There’s also evidence that an increasing number of Poles are questioning Church teaching, with a survey last year by Warsaw’s Center for Public Opinion Research finding that three-quarters of Poles part company with the Church on homosexuality, contraception and extra-marital relationships.

Politically, the Church finds itself struggling to manage its relationship with the ruling Law and Justice party, which came to power in October 2015 with strong Catholic support, and which is still perceived as tightly allied with the Church.

Last month, for instance, one Polish priest publicly suggested that anyone who protests the government should be denied Communion.

Law and Justice is seen as fiercely nationalistic, especially hostile to Russia and Germany; generally anti-immigrant and Euro-skeptical; and, in the eyes of its critics, given to anti-democratic impulses, such as tighter state control over the media.

Of late there have been large street protests, and social divisions are becoming more intense. The Church is probably the only institution capable of calming the situation, and they’re trying; this Thursday, Archbishop Stanislaw Gadecki of Poznan, president of the bishops’ conference, issued an appeal for “national reconciliation.”

Such efforts, however, are harder to realize when the Church is perceived as planted on one side of the street.

Enter Pope Francis. Many observers believe that right now Polish Catholicism would benefit from the following:

- Demonstrating a sincere desire for dialogue with all parties, including those traditionally seen as hostile to the Church.

- Showing that while it’s supportive of efforts to defend Catholic identity and traditional moral values, that doesn’t mean the Church is willing to baptize xenophobia, anti-immigrant backlash, or authoritarian rule.

- Convincing a younger generation that the Church is not exclusively identified with its teaching on sexual morality, and that its aim is not to be the great “Doctor No” of society.

- Rejecting a clericalist ecclesiastical culture and embracing the lay role.

Pope Francis, of course, incarnates those points in full living color.

This July, therefore, the Polish church has an opportunity to revitalize the legacy of a previous pope who’s still the pride of the nation, in part by bundling it with the fresh energy of another pontiff from a “faraway land.”

Just like his Polish predecessor, Francis is a maverick who’s captured the imagination of the world, and whose audacious aim is to change the tides of history. Recent experience suggests that if Polish Catholicism gets into a full, upright, and locked position on that project, absolutely anything is possible.