A document obtained by Crux, related to accusations of sexual and other forms of abuse against the founder of a powerful Catholic lay movement in Peru, suggests that the Vatican was informed of the charges as early as May 2011 but essentially took no action for four years.

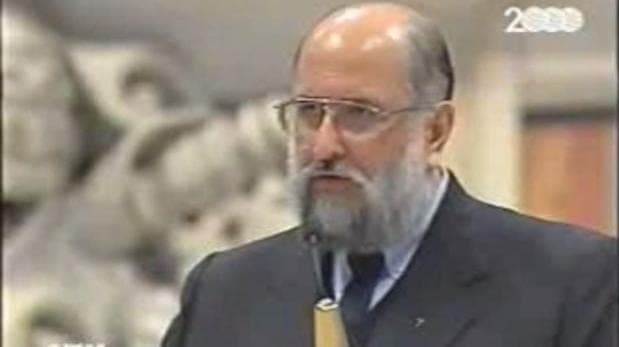

A May 17, 2016, letter addressed to Peru’s bishops by the head of the country’s main ecclesiastical court lists multiple steps taken to inform Rome of allegations against Luis Fernando Figari, founder of the Sodalitium Christianae Vitae (SCV), and expresses mounting frustration at the lack of response.

In April 2015, the Vatican eventually appointed a local visitor to look into the charges, and early last month Rome named American Archbishop Joseph Tobin of Indianapolis, a former Vatican official, as its delegate to lead a process of reform.

In response to a Crux request for comment, the Vatican spokesman, Father Federico Lombardi, said the delay was due to “the complexity and diversity of positions and interpretations” regarding the accusations against Figari, as well as legal issues.

The May 17 letter from Father Víctor Huapaya, president of the main Church court in Lima, the Peruvian capital, shows the tribunal quickly forwarded three complaints by Figari’s victims in 2011 to Roman officials, as well as a fourth one in 2013.

The complaints were sent by Huapaya to the Vatican’s Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life in Rome, known in English by its shorthand title of “Congregation for Religious.”

The congregation has direct responsibility for the SCV, which as an international Institute of Consecrated Life is not subject to the authority of the local Peruvian bishops but answers directly to Rome.

The letter also clearly shows Huapaya’s growing irritation over four years at the lack of response from the congregation, raising questions over the Vatican’s capacity to come to grips with the issue.

In early May, the SCV – known as the “Sodalicio” in Peru – was told it cannot make decisions without Vatican approval, and its founder, Figari, was moved from his expensive Sodalitium-provided apartment in the center of Rome.

A SCV statement gave no details of where Figari has relocated, only that it was a “more isolated place, in accordance with the requirements that the Holy See has requested in order to continue its investigations.”

Crux understands that it is a room in a house run by a religious order on the outskirts of Rome.

[Update: Since this piece was originally published, Crux has learned that Figari has not yet been moved from his SCV-owned apartment. A source close to the leadership in Rome tells Crux: “His departure has been okayed by the Congregation for Religious, but is awaiting the approval of the delegate (Tobin) who has to rubber-stamp all the decisions.”]

So far, Figari has been neither judged nor sentenced, either by civil authorities in Peru or by the Church’s own tribunals.

The SCV, which includes consecrated laywomen as well as priests, is governed by a group of celibate laymen known as “sodalits.” Granted papal recognition in 1997, it has around 20,000 members today in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Chile, Ecuador, the United States, and Italy, in addition to Peru.

Known for its orthodoxy, discipline and evangelizing zeal, the group runs highly regarded schools and charities, but is seen by its critics as an upper-class Catholic reaction against the more social justice-oriented Catholicism in Latin America following the Second Vatican Council (1962-65).

The scandal involving Figari went public in Peru in October last year, when a journalist with the Lima daily La República who is also a former SCV member published a book containing explosive testimony from five former Sodalicio members who chose to remain anonymous.

Half Monks, Half Soldiers, which the journalist, Pedro Salinas, co-wrote with Paola Ugaz, documented physical and sexual abuse, sometimes of minors, over many years, mainly dating back to the 1970s, perpetrated by an inner core of male consecrated members who slavishly followed Figari.

In early April this year, the SCV’s superior general, Alessandro Moroni, finally admitted the abuse, asked pardon of the victims, and publicly repudiated Figari.

Peruvian judicial authorities began to investigate the allegations in December last year, but because the victims did not want to be identified, were forced to drop the case.

According to Salinas, the victims feared being exposed for nothing: because the abuse falls outside Peru’s statute of limitations, they believed they were unlikely to see justice.

Yet long before the Salinas book, three of the victims cited in it had already denounced the abuse to the interdiocesan tribunal in Lima back in 2011.

The three complainants – who felt more comfortable using the Church process because it guarantees confidentiality – are known in the tribunal’s papers as “Santiago,” “Lucas” and “Juan.”

Writing in La República Salinas claims that the accusations sent to the Lima tribunal never reached Rome, and fingers the tribunal’s moderator, the Archbishop of Lima, Cardinal Juan Luis Cipriani, as the reason why.

“It has never been clear where those highly sensitive and serious complaints ended up, or what happened with them,” wrote Salinas in the article.

But the letter seen by Crux sheds a very different light, showing that the Peruvian church acted swiftly, sending each of four complaints against the Sodalitium onto the Congregation for Religious.

The first was by “Santiago” who handed over a written accusation against Figari on May 16, 2011. A week later, Huapaya sent the document to the Congregation for Religious with an accompanying letter from him dated May 24, 2011.

The tribunal received a second complaint against Figari sent from the Archdiocese of Cologne, Germany, in a letter dated May 24, 2011. Huapaya sent the documents to the Congregation for Religious on September 9, 2011.

A few days later, via the papal embassy in Lima, the congregation acknowledged receipt of the two letters.

The third complaint was from the author, Salinas, who wrote to the tribunal on September 13, 2011, which Huapaya forwarded to Rome just under a month later.

In January 2012, Huapaya wrote to the congregation’s Brazilian prefect, Cardinal João Braz de Aviz, asking him to take action. Three months later he received a reply from the congregation’s subsecretary, who confirmed receipt of his letter as well as the complaints against the SCV.

Over a year later, in September 2013 – six months after Pope Francis’s election –Huapaya met with Father Waldemar Barszcz at the Congregation for Religious, who again confirmed receipt of his letter as well as the complaints against Figari.

“I expressed to him my deep concern over the dicastery’s lack of action in response to these complaints and the consequent suffering of the victims,” recalls Huapaya in his letter to the bishops.

(“Dicastery” is the general term for a Vatican department.)

A month later, having still received no news, Huapaya received a fourth complaint. On October 25, 2013, a priest and three SCV members petitioned the tribunal for Figari’s conduct to be investigated.

The documents were forwarded to the Congregation for Religious a few days later, on December 2, with an accompanying letter from Huapaya to Braz de Aviz.

“I insisted that, given the facts made known to his congregation, there was a lack of respect shown to the victims,” Huapaya recalls, “and I reiterated the need for urgent action on the part of the dicastery, given that these were cases that fall under its competence, as I had repeatedly made clear.”

Six months later, in July 2014, the papal envoy to Peru, Philadelphia-born Archbishop James Patrick Green, asked Huapaya to brief him on the Figari case. A few days after the meeting, Huapaya forwarded the relevant documents to Green, again stressing the need for swift action.

At this point, over three years had gone by since the first accusation lodged with the Lima tribunal was sent to Rome. It would be almost another year before Rome responded.

On April 22, 2015, the Congregation for Religious appointed a Peruvian bishop, Fortunato Pablo Urcey of Chota, to carry out an initial investigation.

On May 4, 2016, the Vatican decided to intervene directly in the SCV’s governance, appointing Tobin as the congregation’s delegate, with a power to veto decisions by its governing body.

Figari, however remains free, apparently because of a gap in reforms to canon law to deal with the clerical sex abuse crisis.

When Pope John Paul II in 2003 allowed for the statute of limitations to be scrapped in the case of sexual abuse of minors, the change covered priests, not laypeople or religious brothers. Because Figari is a layman, therefore, the statute of limitation still applies.

But the question remains why, for so long, there had been so little response from the Vatican.

Lombardi, the Vatican spokesman, told Crux by email that the congregation had been at pains to act prudently “given the complexity and diversity of positions and interpretations surrounding Figari and the Sodalitium,” as well as “considerations of a legal character.”

“It was necessary to carry out a thorough examination, keeping in mind the ecclesial and social context of Peru, and the fact that some of these accusations didn’t have the necessary requisites to be taken as the basis for action by the congregation,” Lombardi’s statement said.

“Since the first accusations [against Figari] referred to in the [tribunal] letter, the documentation has grown considerably and is being evaluated in the light of possible decisions to be taken,” he added.

A senior SCV member told Crux on background that caring for and compensating victims is now a priority of the Sodalitium, but that bringing Figari to justice remains a challenge because of the law as it stands.

Since December, “we have been begging the Vatican forcibly to exclaustrate Figari,” he said, meaning to formally remove him from the group, but because Figari is not bound by religious vows, denies the allegations, is unrepentant, and is defended by a high-profile lawyer, the member suggested the Vatican congregation may fear that any ruling against him would be fought on appeal.

For now, Figari’s continued impunity, combined with evidence of a previous lack of action in Rome, can only contribute to the victims’ frustration.