ARLINGTON, Virginia — As part of a two-year preparatory period leading up to its golden jubilee in 2024, the Diocese of Arlington has embarked on a spiritual and intellectual renewal in the foundational truths of the Catholic faith.

For the first year of preparation, the focus is the Eucharist and priests around the diocese are giving talks explaining the Mass.

Father Noah C. Morey, chaplain of Bishop Ireton High School in Alexandria, recently gave the first presentation at St. Agnes Church in Arlington.

Where did the Mass come from?

The origins of the Mass come from the Bible and the early church. Church documents that explain how the early church worshipped and prayed include the Didache, which dates back to A.D. 80; the First Apology of St. Justin the Martyr, written around A.D. 155; and the Apostolic Tradition, written by St. Hippolytus around A.D. 215. “In the first three centuries of the church, we have all of the roots of the Catholic Mass,” said Morey. Much of the language of the Mass is taken directly from Scripture.

Introductory Rites

A Mass celebrated on Monday, a Sunday Mass and a Christmas Mass all look a little different. That’s because greater solemnities are celebrated with “increasing flourish and ritual,” said Morey, which could include more singing or the use of incense.

Sunday Mass begins with a procession, led either by an altar server carrying a cross or a thurible, which holds burning incense. The congregation stands out of reverence for the priest, who represents Christ. The procession leads to the sanctuary, which is reminiscent of the holy place in the Jewish temple.

The priest then approaches the altar and kisses it to show reverence to the relics of the saints that are enclosed in the altar. In the early church in Rome, Mass was celebrated underground and the tombs of Christians served as altars.

The priest begins with the sign of the cross and the words, “In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit,” invoking the Trinity and signifying God’s presence among his people. He follows with, “The Lord be with you,” and the congregation answers, “And with your spirit.”

“The Lord be with you” is an ancient exhortation found throughout the Bible, such as when an angel appeared to the prophet Gideon or to the Virgin Mary. “(The message) was to encourage them and strengthen them for the task that God was going to ask them to do,” said Morey. “It shows us that we can’t do this on our own. The Lord is with us and he is the source of our strength. He still wants to greet and inspire us to do good things through him.”

The next part is the penitential act. “In the early church, it involved an examination of conscience followed by a public confession of sins,” said Father Morey. “Fortunately, today we don’t have that part, but we do have an acknowledgment of our own unworthiness as well as a public acknowledgment of our sins.”

The Kyrie Eleison, the only part of the liturgy still in Greek, means “Lord, have mercy.” The Gloria is a hymn of praise, echoing the song of the angels to the shepherds on Christmas night. The Collect concludes the opening prayers, and the words change depending on the day.

At that time, the priest stands in the orans position — Latin for praying — extending his hands outward. “Whenever the priest prays on behalf of the people he will extend his hands,” said Morey. “This goes back to the psalm which talks about the raising of hands as an evening oblation, our prayers going up to God. But since the priest is standing in the person of Christ, he also takes on the cruciform look.”

Liturgy of the Word

Before the Second Vatican Council, the Lectionary cycle, or the readings, were the same every year. But after Vatican II, in order to bring more of the Scriptures into the Mass, a three-year Lectionary cycle was instituted for Sunday Masses. Usually during Year A, the primary Gospel readings are from Matthew, in Year B they are from Mark and in Year C they are from Luke; John is interspersed throughout, especially during the Easter season. Weekday Masses are on a two-year Lectionary cycle.

The first reading is from the Old Testament, except during the Easter season when it comes from the Acts of the Apostles. The first reading corresponds with the Gospel, often showing how an Old Testament prophecy is fulfilled by Christ. Next, a passage from the Psalms is sung. Many of the psalms were written by King David for temple worship. The second reading comes from the New Testament. At the “Alleluia,” the congregation stands and praises God before the Gospel is read by the priest or deacon.

The homily helps the faithful understand the readings and makes the Word of God relevant for today. Then the priest will move from the ambo, or podium, back to his chair where he will lead the Nicene Creed, a statement of the teachings that come from the Council of Nicaea in A.D 325 and the Council of Constantinople in A.D. 381. The Liturgy of the Word concludes with the prayers of the faithful, in which the congregation presents its petitions for the good of the community and the world.

Liturgy of the Eucharist

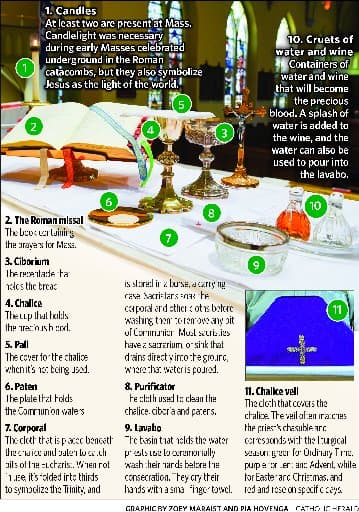

After the priest has set up the altar, he receives the offertory gifts, usually a receptacle called a ciborium containing the Communion wafers and a cruet of wine. Monetary donations often are collected at the same time.

“In the early church, when (Christians) attended the liturgy, they would bring whatever was their trade or their crop,” said Morey. “This reminds us that just as bread comes from many grains and wine comes from grapes, so also our sacrifices collectively are brought up and presented to the Lord. It was about the 11th century that a monetary collection was taken up and that was the symbolic way of the people bringing their gifts to be presented to God.”

A splash of water is added to the wine, referred to as the co-mingling of the water and wine. In the early church it was done to dilute the strong wine, but it also symbolizes Christ’s humanity and divinity. The priest prays silently, “By the mystery of this water and wine, may we come to share in the divinity of Christ, who humbled himself to share in our humanity.”

The priest then washes his hands with water from a basin called the lavabo, which means “I will wash” in Latin, harkening back to when God instructed Aaron, the brother of Moses, to wash his hands and feet before making an offering to God. The priest then invites the people to pray that their sacrifice may be acceptable to God before beginning the Eucharistic prayer. The words of the Sanctus, which begins “Holy, holy, holy,” echo what the prophet Isaiah heard the angels sing and what the people called out to Jesus as he entered Jerusalem on a donkey. The congregation then kneels as a sign of reverence.

The priest continues with a prayer of adoration and then extends his hands over the bread and wine and calls down the Holy Spirit in the part of the eucharistic prayer called the epiclesis. During the consecration, the priest says the words Christ spoke at the Last Supper. The bread and wine becomes the body and blood of Christ through the mystery of transubstantiation.

After the eucharistic prayer concludes, the whole congregation stands and prays the Our Father, which was added to the liturgy by St. Gregory the Great around A.D. 600. The sign of peace, which often is exchanged among Massgoers, is a reminder of Jesus’ command to reconcile with one’s brother before making an offering to God. Then the clergy and extraordinary ministers of holy Communion distribute the Eucharist. When a person says “Amen” to the words “Body of Christ,” they are affirming not only their belief in the Eucharist, but in the totality of the church’s teachings. After Communion, the priest returns to the altar for the ablutions, or cleaning.

Concluding Rites

Mass concludes with a prayer, a blessing and the dismissal — the missionary mandate to go and announce the Gospel of the Lord.

– – –

Maraist is a staff writer at the Arlington Catholic Herald, newspaper of the Diocese of Arlington.