As nations of the world attempt to deal with our current pandemic, and its accompanying quarantine, there has developed a renewed battle over the question of freedom. In listening to the civil discourse (and “civil” is used here with reservation), it appears there are many questions surrounding the nature of freedom, its spiritual dynamism, and the conditions under which it can (or should) be restricted.

Freedom asserts the dangerous belief that people know how to govern themselves and how to live in a way that enriches their lives and that of the common good. As such, there is a danger to freedom, since people are fallen. Freedom can be exaggerated or abused. It can be used to cause hurt, harm, or negligence.

People can cite “freedom” to injure their own bodies, dismiss civic laws and policies, and cause threats to public health. Such possible abuses of freedom are popularly cited, as if they are contemporary deviations peculiar to our present circumstances. But such abuses have always occurred whenever freedom has been attempted.

Such licentiousness and exaggerations of freedom have consistently been found within the interior logic of freedom itself. Freedom, as freedom, has always been uncontrollable and possibly dangerous.

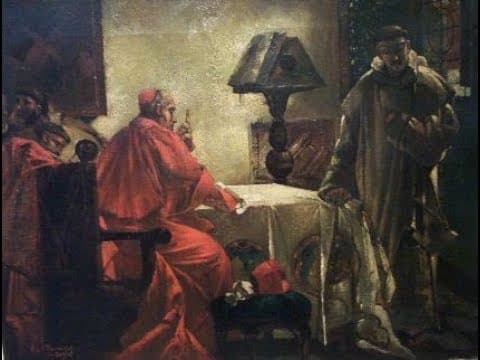

Such possible danger is denounced by the fictional character of the Grand Inquisitor in the Russian novel, The Brothers Karamazov. In the disturbing account of the inquisitor, Jesus Christ returns to the earth, works miracles, and gives hope to people. But he is quickly arrested and scrutinized by the inquisitor. The examiner tells Christ that he is no longer needed. He mocks the freedom that Christ has given to humanity, and tells the Savior that he misjudged human nature.

The inquisitor argues that people don’t want to be free and cannot be trusted with freedom. He declares that people simply want (and need) benign rulers. He argues that humanity should not be given freedom. It’s too dangerous, too unreliable, and too uncertain. The inquisitor believes that freedom must be restricted. People should be controlled by fear and led by harsh rulers.

The creed of the Grand Inquisitor is unsettling. It’s the end of freedom. And yet, his voice whispers into the ears of leaders and societies, sometimes in veiled and nuanced ways and at other times with boldness and without apology. Freedom cannot be trusted, we are told. People must be controlled.

The fluidity of freedom, and its possible dangers, do not always justify its restriction. Human persons were created to be free. We are at our best when we are free. And as good spiritual wisdom teaches us, an abuse of a good does not negate its use. Simply because freedom could be dangerous does not, by itself, justify muzzling it by authority.

In fact, it is precisely the dangerous nature of freedom that makes it such a dynamic source of creativity, ingenuity, and renewal. It is bold, risky, and unpredictable. And that is why freedom has always been feared by raw power in whatever form it’s exercised. It’s also why freedom has always been the impetus for civil disobedience, the birth of new ideas, and the flourishing of culture.

A sober observation of human history reveals that freedom gives a person the power to do what is right and good. This is why in order for freedom to grow, it needs education, lived experience, virtue, and seasoned guidance. This is the where the real work of authority should be found. The task of leadership is to be a teacher, not an inquisitor.

This is why freedom loses its bearings, implodes, and becomes codependent on civic authority when it is repressed, overly regulated, and sequestered in its ingenuity. Freedom is crippled by Grand Inquisitors, just as it flourishes under Good Shepherds and Good Teachers.

With the turbulent nature of freedom in mind, however, there are times when the teaching by civic authority must exercise discipline and establish perimeters to freedom. At times, there are justifiable reasons to give prudential boundaries to the exercise of freedom, especially when it involves the common good. Such measures, however, should always be approached with keen discernment, caution, and serious oversight. They should always be given with the intention of nourishing freedom itself and eventually outrunning their course.

Freedom is an exercise of the our souls and, as such, it needs itself – without needless chains – to develop, auto-correct, and aspire to greater goods.

For those in the civil discourse, therefore, and those who hold authority over the common good, freedom is to be seen as a sacred trust. It is not the province of government. Freedom belongs to the people. Its protection is entrusted to civic authority by the people.

As such, public servants should avoid the alluring whispers of the Grand Inquisitor. In all its decisions, civic leadership is called to believe in freedom, and to use its authority hesitantly in the delicate balance of protecting both the common good and individual freedom itself.

Follow Father Jeffrey Kirby on Twitter: @fatherkirby