When my children were young, we had a Christmas Eve tradition. We read “The Polar Express” out loud, around the tree, before bed. Back then, I thought writer and illustrator Chris Van Allsburg’s haunting creation was simply an ode to a child’s need to keep believing in the unseen, Santa Claus. Now I see it as more than that: an ode to the need to keep believing, period, when we’re all grown up.

“The Polar Express” is about faith, Van Allsburg has said himself, “and the power of imagination to sustain faith. It’s also about the desire to reside in a world where magic can happen, the kind of world we all believed in as children, but one that disappears as we grow older.”

“The rationality we all embrace as adults makes believing in the fantastic difficult, if not impossible,” he said. “Lucky are the children who know there is a jolly fat man in a red suit who pilots a flying sleigh. We should envy them.”

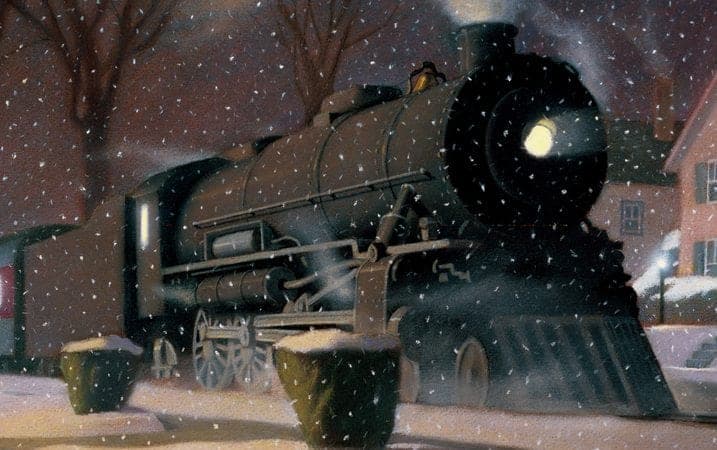

In case you don’t know the “Polar Express” story, on Christmas Eve a young boy lies in bed listening for the bells on Santa’s sleigh. A friend had just told him Santa isn’t real. What he hears instead of bells is the hiss of a steam engine right outside his front door. A conductor invites him aboard “The Polar Express,” already filled with children on their way to the North Pole, and the boy, mesmerized, hops aboard.

Once the boy gets there (the illustrations, if you’ve not seen them, are truly magical), he’s chosen to receive the first gift of Christmas, whatever he wants. He chooses a silver bell from Santa’s sleigh, which Santa immediately gives him. When the boy gets back on the train, he realizes, heartbroken, that the bell has fallen through a hole in his bathrobe pocket.

But on Christmas morning, his sister Sarah finds a box with his name on it beneath the tree. Inside is the silver bell, delivered to him by Santa, who found it on the seat of his sleigh. When the boy rings the bell, both he and Sarah are enchanted by its sound. But his parents can’t hear it. They think the bell is broken. The book ends with this quote:

“At one time, most of my friends could hear the bell, but as years passed, it fell silent for all of them. Even Sarah found one Christmas that she could no longer hear its sweet sound. Though I’ve grown old, the bell still rings for me, as it does for all who truly believe.”

Chris Van Allsburg has written many children’s books, including “Jumanji,” “Ben’s Dream,” and “The Mysteries of Harris Burdick.” Most deal with a favorite theme. “The idea of the extraordinary happening in the context of the ordinary,” Van Allsburg has said, “is what’s fascinating to me.”

It fascinating to me as well, since faith can turn the ordinary into the extraordinary, the mundane into the miraculous. To paraphrase the monk Thomas Keating, faith can change the way you see the whole world: It’s the difference between watching a TV in black and white, and watching it in Technicolor.

There is another, lesser-known Christmas passage about child-like faith in the unseen and a mother’s yearning for that easier, innocent faith. Annie Dillard wrote it with a bittersweet mix of the joy, longing, and sadness that marks Christmas for so many. Best known for her Pulitzer Prize-winning “The Pilgrim at Tinker Creek,” Dillard wrote this particular passage in her autobiography, “An American Childhood.” It was published around the time she converted to Catholicism, though her website now lists her religion as “none.”

Her mother, Dillard wrote, married into a rich family of charming but hard-drinking carousers who died young and set a “dashing, doomed tone for the town.” Her mother’s own dashing and doomed father, she said, “died at forty-one, when Mother was seven, and left her forever full of longing.”

The passage:

Late at night on Christmas Eve, Mother carried us each to our high bedroom, and darkened the room, and opened the window, and held us awed in the freezing stillness saying — and we could hear the edge of tears in her voice — ‘Do you hear them? Do you hear the bells, the little bells, on Santa’s sleigh?’ We marveled and drowsed, smelling the piercingly cold night and the sweetness of Mother’s warm neck, hearing in her voice so much pent emotion, feeling the familiar strength in the crook of her arms, and looking out over the silent streetlights and the chilled stars over the footsteps of the town, ‘Very faint and far away — can you hear them coming?’ And we could hear them coming, very faint and far away, the bells on the flying sleigh.