YAOUNDÉ, Cameroon – Outside the gates of the Kondengui maximum-security prison in Cameroon’s capital, Yaoundé, ordinary people on the evening before Easter could be found drinking and dancing in bars. But inside the prison, Yaoundé Archbishop Jean Mbarga was visiting the inmates, some of them former senior government officials now serving time for corruption.

“Even after death, Jesus Christ is able to get you out of the grave,” the archbishop told the inmates, who included former Prime Minister Ephraim Inoni; former Secretary-General at the Presidency, Jean-Marie Atangana Mebara; and the former minister of Water Resources and Energy, Basile Atangana Kouna.

“After your incarceration, he will get you out of this place,” Mbarga said. “The Lord who did it for you yesterday and today will surely do it for you tomorrow.”

The archbishop went ahead to underscore the need for public officials to enhance the common good, wondering why the Cameroonian society had become “so corrupt, so full of crime.”

“Our cities and towns are afflicted by a rise in drug consumption that kills our youths. Armed robbery is on the rise, and this sows fear amongst the people. Assaults on pedestrians and passengers in taxis have become a regular feature in our country. Dangerous gangs are in our midst. Children are kidnapped every day,” the archbishop said.

He said this “proximity violence” was a sign of the “rising culture of death” in Cameroon.

“The resurrection of Christ calls on all of us – particularly young people – to reconstruct the culture of life,” Mbarga said.

Building a culture of life, he explained, means enhancing the common good – an apparent swipe at the high-profile prisoners who siphoned billions from the public purse to foster their private wellbeing – even as the population goes without access to potable water, electricity or basic healthcare services.

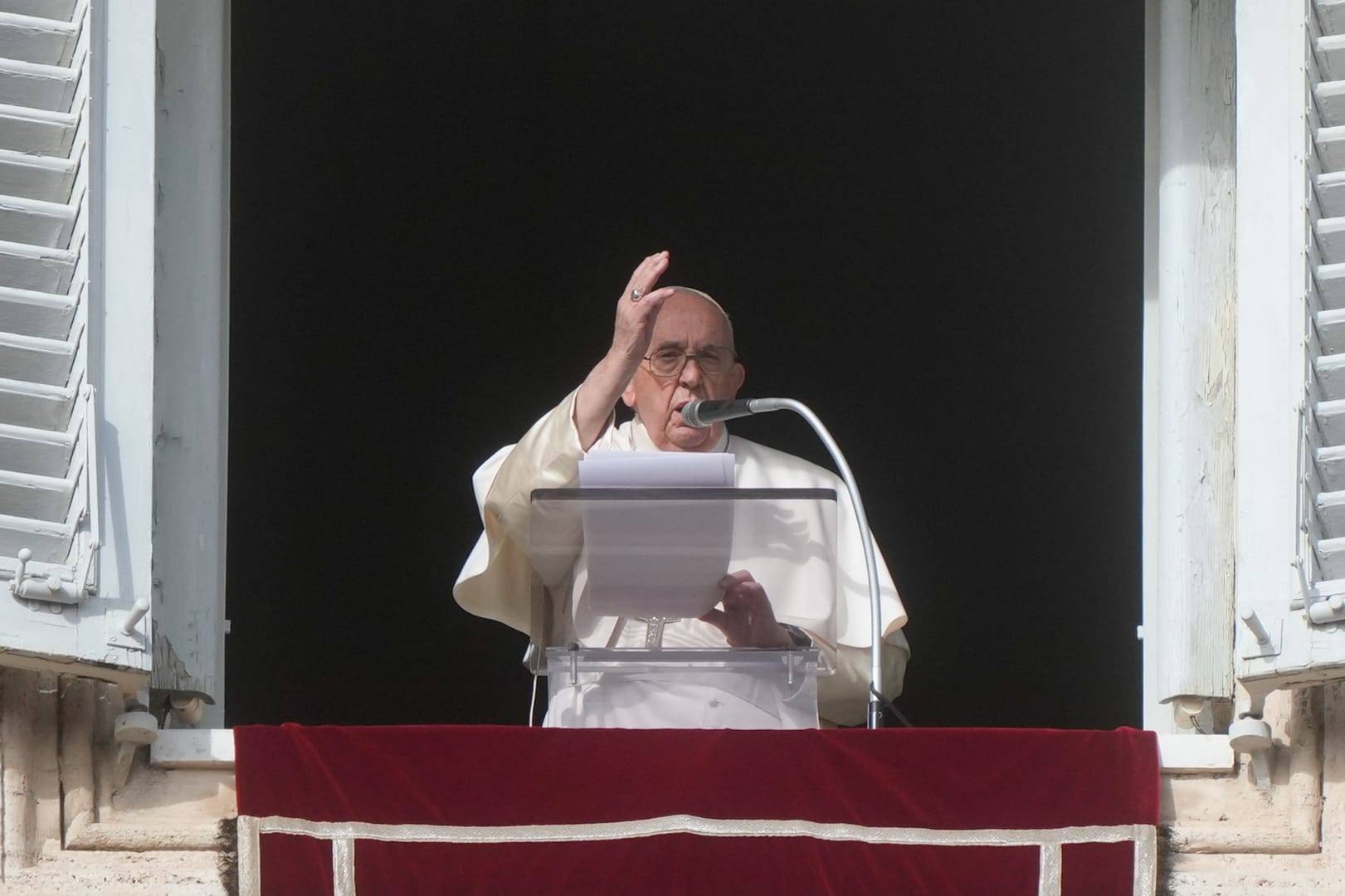

The archbishop’s visit echoed the Holy Thursday visits of Pope Francis, who this year went to Rome’s Regina Coeli prison. In 2017, Francis visited Paliano prison outside the Italian capital, which housed high-profile mafia turncoats.

RELATED: During prison visit, Pope calls leaders to service, repeats opposition to death penalty

In Kondengui, the archbishop’s message was well received.

The former director-general of the Cameroon Petroleum Depots Company, Jean-Baptiste Nguini Effa, who is serving a 30-year sentence for stealing over $350,000, told Crux, “When you have faith in Christ, prison doesn’t become a grave.”

“We resurrect with Christ and we will be free,” he said.

“No one can be as free as when he is in jail,” he continued, noting that prison has brought him closer to God and he is “indeed free.”

But critics were quick to observe that even in prison, the former senior state officials were being treated differently than the rest of the inmates.

“When the archbishop came, he greeted the so- called high-profile or VIP prisoners,” Nyounai Nyounai – a retired civil servant – told Crux.

“In addition, the VIP prisoners were well dressed in well-tailored and smartly ironed suits, and they were seated under the canopy. Ordinary prisoners – many of them guilty of minor crimes – were seated on the ground under the searing heat. That kind of discrimination shows that the bigger the thief, the more respect he is accorded – even in jail,” Nyounai said.

A call to improve prison conditions

The archbishop noted that while it is right and fitting that people who break the law should be made to account for their crimes, he said making prison a punishing experience was a violation of the rights of prisoners.

“They have a right to be treated with dignity,” he said.

Overcrowding has become common for prisons in Cameroon, especially with a military crackdown on an ongoing protest by English-speakers seeking more autonomy leading to even more arrests.

RELATED: Cameroon cardinal accuses military of abuses in fight against Anglophone separatists

According to figures from the Cameroon Justice Ministry, the Kondengui prison, constructed for 750 inmates, now holds more than 4,000 people.

Amnesty International in 2011 issued a report stating conditions at Kondengui were unacceptable, “with inmates suffering overcrowding, poor sanitation and inadequate food.”

Across the country, there are already over 30,000 people held in the country’s 78 prisons, originally built to house 17,000 inmates, according to the country’s Justice Minister, Laurent Esso.

Most of the inmates have not even been convicted, and are still awaiting trial, according to Cameroon’s Commission on Human Rights and Freedoms.

“You find so many young men languishing in jail – young men and women who should be helping to grow the economy. And they are tortured. A prison should be a place for reformation and not a torture chamber,” Chemuta Divine Banda, the commission’s chairperson, told Crux.

For the archbishop though, a true conversion of the individual will help the inmates find an inner peace, and “when they come out, they will be better persons in society.”

A call for peace in the country

Against the backdrop of rising attacks, especially in Cameroon’s English-speaking regions, Mbarga made the case for peace in Cameroon.

Such peace, he said, would come through respect for state institutions, but more importantly, through adherence to the symbolism of the risen Christ.

Since 2016, Anglophones in the country have been asking for their rights to be respected by the French-speaking majority. Some of them are now calling for outright secession – to create a new nation called Ambazonia – which has led to a harsh crackdown by the central government.

“The peace of the risen Christ is more than the silence of guns,” the archbishop said.