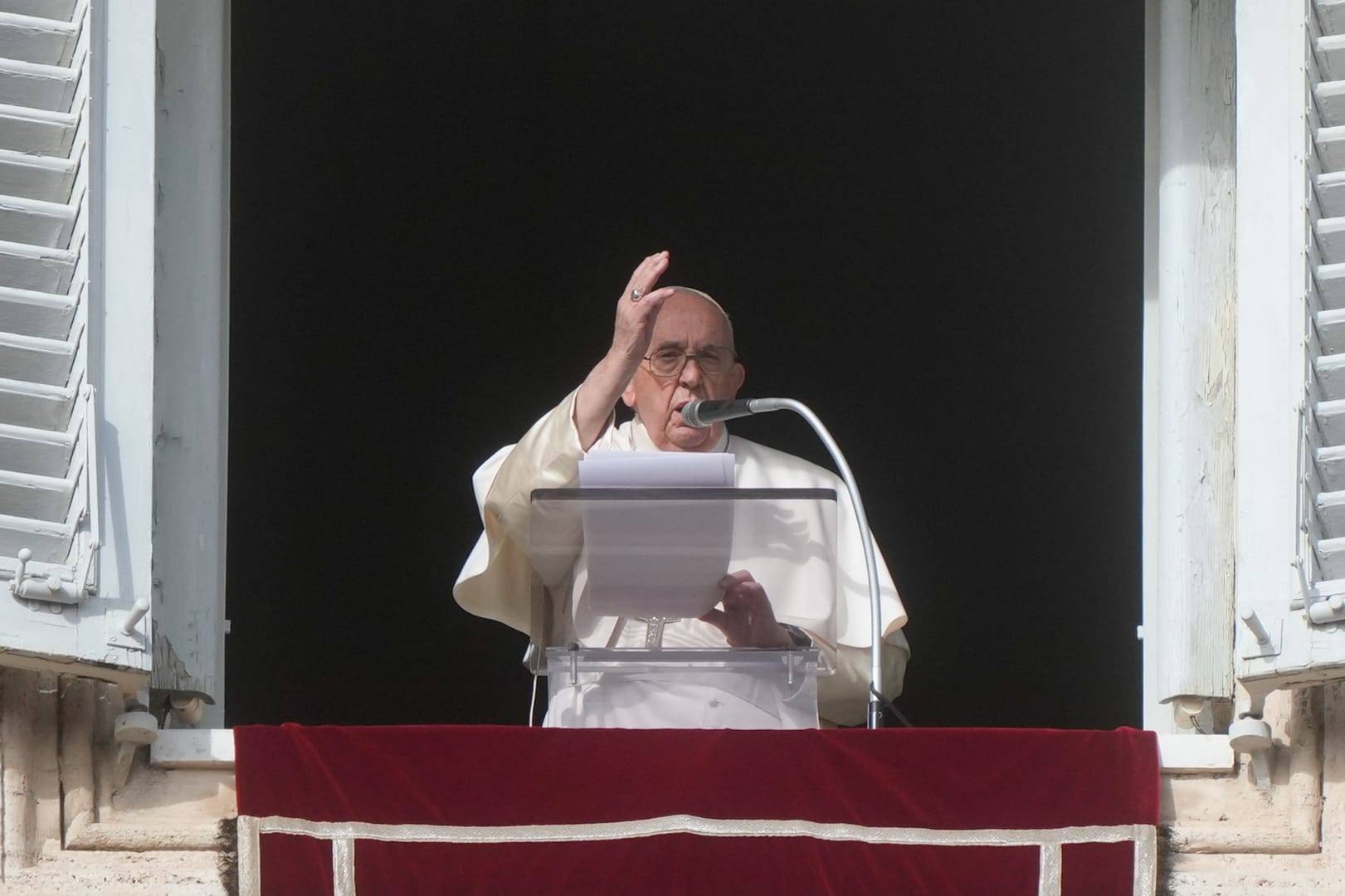

ROME – In September Pope Francis will be visiting the southern Italian island of Sicily, where, in his usual style, he’ll meet youth, the poor, infirm persons, immigrants and detainees.

Not on the list, however, is the Archbishop of Catania, who’s currently charged with embezzlement of funds destined for people with disabilities.

On September 15, Francis will land at Catania’s airport before taking a helicopter to the Sicilian town of Palermo, but the Vatican has confirmed there will be no greetings with the local curia.

While the pope is known for his touch-and-go trips, not meeting with the Metropolitan Archbishop of Catania, Salvatore Gristina, has raised a few eyebrows, especially considering that he heads the Sicilian bishops’ conference.

“I will come to Sicily for a pastoral visit,” Francis reportedly told an Italian journalist May 14 after Mass at Domus Santae Martae where he lives.

The Vatican has confirmed the trip, which will occur on the 25th anniversary of Blessed Pino Puglisi, a priest from Palermo killed after challenging the local Mafia.

Sicily holds a special place in the Francis pontificate. It was the first place he visited as pope in July 2013, when he threw a flowered wreath in the Mediterranean Sea to mourn the death of migrants.

Francis has also expressed closeness to the Sicilian people in the fight against the mafia, which he has often condemned and described as “evil.” In a message sent to Sicilian bishops in May, the pope invited them to learn from the example of Puglisi to hold off corruption.

“The plots of evil are fought with daily practices,” Francis told the bishops.

For years cases of financial mismanagement, criminal activity, sexual abuse and moral transgressions by religious and lay people have littered the island. There’s no doubt that the Church in Sicily represents a sui generis situation on the Italian peninsula, something the pope seems to have caught on to early on.

On one hand, Francis chose to make the Archbishop of Agrigento, Francesco Montenegro, a cardinal after their meeting in Lampedusa, a decision that defied the practice of giving the red hat to the bishop in the capital of Palermo. On the other, he made a simple parish priest, Corrado Lorefice, active in the fight against the mafia and human trafficking, the Archbishop of Palermo in 2015.

The three-pointed island of Sicily, known for its independent streak and impenetrable corruption, has become one of Francis’s “pan-flipping” experiments where a local hierarchy has been overturned to both enthusiasm and disappointment.

Whether the pope’s efforts will yield any tangible results is still to be determined in a region that has stubbornly resisted waves of change. After all, it was the author Tommaso Lampedusa who in his novel The Leopard best described the Sicilian spirit: “For things to remain the same, everything must change.”

Archbishop entangled

The Metropolitan Archbishop of Catania, Salvatore Gristina, was accused in mid-July of embezzlement as president of the Board of the Diocesan Works for Cult and Religion of Catania (Odccr) in collusion with the Diocesan Assistance Works (Oda) of Catania, a clergy-controlled organization that provides assistance for people with special needs.

Oda is the most important organization of its kind in Sicily, caring for over 1,500 disabled people with about 500 employees. The charge against Gristina is that he stole over $200,000 from the Oda fund.

Denying the charges, Gristina has said that he has “the highest respect for judicial authority” and that he awaits the moment when “the absolute legitimacy of his actions will be ascertained.”

From the beginning, the archbishop’s restrained personality, tempered by his experience as a papal envoy in Ivory Coast, Trinidad and Tobago and Brazil, came across as a bit distant to the people of Catania, especially when compared to his charismatic predecessor Archbishop Luigi Bommarito.

Though more of a diplomat than a fire-and-brimstone preacher, Gristina has promoted the importance of the parish, emphasized closeness to the people and called his community to mirror Puglisi’s example.

When Gristina came to Catania in 2002, he faced the challenges of cleaning up the troubled diocese, especially the archiepiscopal seminary, rumored for decades to be in complete disarray; managing the feast of St. Agatha, permeated by the mafia; and of course, handling Oda.

The organization stuck in the craw of the archdiocese, with a debt as high as $50 million in 2017 and a backlog of unpaid salaries. Workers resorted to protesting at the door of the archbishop, and even in the cathedral. In December 2016, the president of Oda, Alberto Marsella, handed in his resignation, creating a rift within the administration.

Gristina decided to remove the entire board of directors and called in a lawyer named Adolfo Landi to act as extraordinary commissioner. The archbishop probably didn’t expect the situation to backfire the way it did, since Landi found “anomalies” that made Gristina a target of investigating magistrates.

Marsella now is accused of misappropriation along with the Oda employee Daniela Stefania Iacobacci. The two are charged with stealing nearly $10,000 from the monthly payments destined for a Lay of Lourdes retirement home near Catania between October 2016 and January 2017.

But the anomalies also showed over $200,000 being moved with a false contract for a home in the center of Rome. The two parties involved were Oda, led by father Alfio Santo Russo, and Odccr, presided over by Gristina.

A criminal trial, which still has no fixed date, will decide Gristina’s guilt or innocence, but some locals point to signs of recovery.

Today Oda is still standing, and Landi told local news outlets that the employees will not lose their jobs. Sicilian newspapers have also celebrated the “re-conquest” of the Feats of St. Agatha, seemingly purged from the mafia’s influence.

Critics doubt these successes are due to Gristina’s influence, and, in 2021, when he reaches the age of 75, many expect Francis to accept his resignation. In any event, a looming snub in mid-September would seem a fairly clear signal that the pontiff intends to keep his distance in the meantime.