MASKWACIS, Alberta — Young. Indigenous. Committed to the Catholic faith.

Three hundred years after her death, St. Kateri Tekakwitha — North America’s first indigenous saint — has become a model for young people, especially in Maskwacis, a community that includes four First Nations south of Edmonton. Each year they celebrate the saint as one of their own.

“It’s such a blessing to have a native saint. Most of our people don’t understand or know what is a saint; that’s one of the things we want to have out there,” said Karen Wildcat, who organized the fifth annual St. Kateri Gathering July 14 at Our Lady of Seven Sorrows Parish.

“If they can only come to understand how important that is, that we do have a saint that we can pray to and offer sacrifices and fasting. We could help our community more to know the humble life she lived,” Wildcat said.

Known as the “Lily of the Mohawks,” St. Kateri was born in 1656 in upstate New York to a Catholic Algonquin mother and a Mohawk chief. After her baptism, she lived a faith-filled life until her death from tuberculosis in 1680 at age 24.

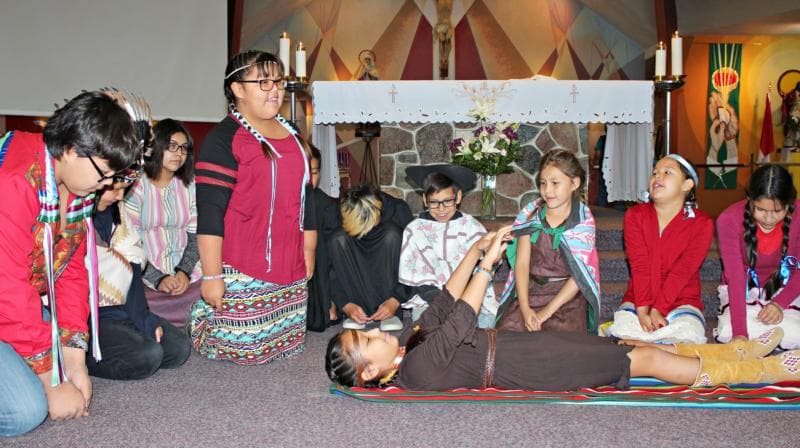

For five years now, Our Lady of Seven Sorrows Parish has been celebrating her life with Mass and a traditional lunch of soup and bannock. This year, kids in costume performed a play based on the life of St. Kateri, a visual display that Wildcat said is crucial for her community.

“For most of our native people, you need to see things to be able to understand. It’s important because she was canonized as our native saint, and she’s for Mother Earth and the environment, and our native people are really sacred about the land and the water and the air.”

Children said they were learning more about the young saint with a background similar to their own.

“She shows respect for everyone,” said Issac Ermineskin, a ninth-grade student who was taught about St. Kateri in his parish youth group and acted in the St. Kateri play with his 10-year-old sister, Bobbi-Ann. “Not all natives like Christianity, but I do.”

What did Bobbi-Ann learn from St. Kateri? “To love others and to be peaceful.”

Many indigenous people can relate to St. Kateri as they come to know more about her, said Father Susai Jesu, who led this year’s Kateri Gathering in Maskwacis.

“The indigenous people begin to feel ‘Wow, she is one among us.’ She went through all kinds of trials of life and she has been a model. They feel affiliated in their blood. She is a part of us,” said Jesu, pastor at Sacred Heart, an Edmonton parish with a large indigenous congregation.

Wildcat learned about St. Kateri at a conference in Ottawa nearly two decades ago. The event included a side trip to the St. Kateri shrine in Kahnawake, Quebec. Years later, Wildcat was asked by Mary Soto — the founder of the Kateri Gathering — to help organize the event in Maskwacis.

Miracles and answered prayers continue to be attributed to St. Kateri.

Father Glenn McDonald, a guest speaker at this year’s Maskwacis gathering, said St. Kateri’s intercession alleviated the depression of one of his former parishioners — and helped him heal from his own bouts of eye cancer.

“I asked St. Kateri to help me because I was scared, but I didn’t see how” she was going to do that, said MacDonald, who feared he would be blind in one eye. His last surgery was on St. Kateri’s Canadian feast day, April 17.

Jesu said he, too, relies on St. Kateri’s intercession. In 2012 he asked for her help in his attempt to get a traditional First Nations drum through customs. Jesu and 12 indigenous leaders from Pelican Narrows, Saskatchewan, were en route to Rome for her canonization ceremony.

“Kateri was there to help us go through this process and (we) eventually saw her guiding presence there,” Jesu said. “We drummed and sang. The whole world was watching it. There were lots of people singing, but nobody had a drum.”

On a larger scale, Jesu noted St. Kateri’s canonization continues to help heal the relationship between indigenous people and the Church, after years of abuse in residential schools.

“I think Kateri herself, as a saint now, (is) interceding with our Lord Jesus Christ for reconciliation and to feel they are all part of the Church. We all belong to one faith as a family of God,” he said.

For MacDonald, St. Kateri’s canonization bodes well for a future apology by Pope Francis for the abuse suffered by indigenous people. A personal apology from the pope on Canadian soil is one of the calls to action stemming from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which examined the legacy of the residential schools in Canada.

MacDonald said he’s confident an apology will happen soon, noting that St. Kateri — considered a model of holiness — was brought to the faith by Jesuit missionaries, and Francis is the first Jesuit pope.

Ehrkamp is news editor of Grandin Media, based in Edmonton, Alberta.