[Editor’s Note: This is part one of a Crux interview with Mark Riebling on his book Church of Spies: The Pope’s Secret War Against Hitler. Part two of Gerald Korson’s conversation with Riebling will appear tomorrow.]

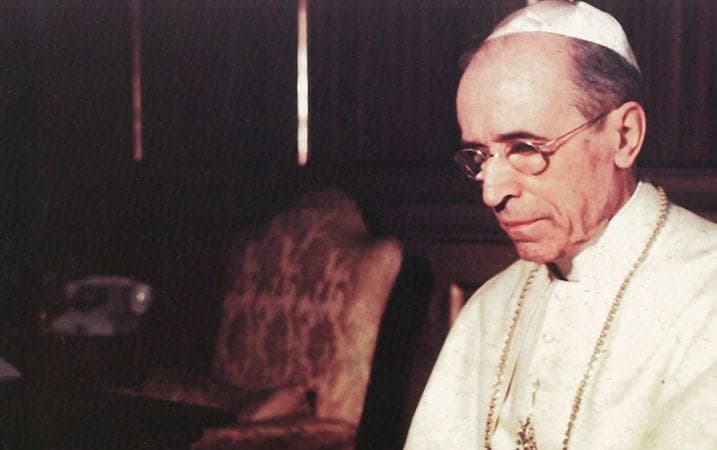

Praised by contemporaries for his heroic efforts on behalf of the Jews and in standing up to totalitarianism during World War II, yet reviled by certain modern-day critics for his alleged inaction and “silence” in the face of Hitler’s rise to power and assault on Europe: Such is the mixed legacy of Pope Pius XII, who sat on the Chair of Peter from 1939 to 1958.

Where does the truth lie?

The praise of Pope Pius XII from Jewish and world leaders during and in the years following the war is well-documented. Accusations began to surface with the revisionist history presented in The Deputy, a 1960 play that cast the pontiff in a decidedly negative light, and continue to be rehashed in the media and in books such as John Cornwell’s Hitler’s Pope, published in 1999.

Authors such as Ronald Rychlak (Hitler, the War, and the Pope, published in 2000) have risen to the pope’s defense, but with far less attention in the secular media than is given to his detractors.

Now comes Mark Riebling, an American historian and policy analyst who has researched and written on matters of national security and terrorism.

In his new book, Church of Spies: The Pope’s Secret War Against Hitler (Basic Books, 2015), he turns his meticulous attention to the whole matter of Pope Pius XII and what he really did — or did not do — during Hitler’s ascendancy and in the face of the evils perpetrated by the Nazis and Fascists in the Second World War.

Digging deeply into the Vatican’s archives and other documented sources, Riebling reveals how Pius XII, far from practicing silent indifference to what was happening, was busily waging his own war against Hitler through clandestine efforts to undermine his objectives and even to oust him from power.

Crux recently interviewed Riebling about his book, his research, and his conclusions regarding the controversy over Pope Pius XII.

Crux: Defenses of Pope Pius XII have been published in the past, but Church of Spies surfaces evidence not previously reported. What inspired you to undertake the investigation?

Riebling: I was researching my book Wedge in the National Archives in Washington, the subtitle of which is The Secret War Between the CIA and FBI, when I came across ten U.S. intelligence documents linking Pope Pius XII and his close advisers to three German military plots against Hitler.

That the Vatican had been involved in these plots had been known in a vague, general way since 1946, when the communist press referenced the pope’s role in the plots, and the Vatican’s newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano, admitted that the claims had some basis in fact.

Since then, even the pope’s fiercest critics — John Cornwell (author of Hitler’s Pope), James Carroll, Daniel Goldhagen, even Rolf Hochhuth (author of “The Deputy”) — they’ve all granted, in passing, that Pius plotted against Hitler. But no one seemed curious about exploring the whole story, or telling it in detail.

As a result, one of the most astonishing events in the history of the papacy had failed to pierce public consciousness, so I set out to give the truth its due.

You were raised a Catholic, but left the faith and now self-identify as an atheist. Does your present belief system in any way color your perspective on this subject matter?

I’d call myself a “Catholic atheist,” if that makes any sense to you. I lack the belief piece, but one of my favorite quotes is by Oriana Fallaci — “The atheist should behave as if God exists.” So, I go to Mass, and recently, in the Vatican, after meeting Pope Francis, I even went to Confession in the Jesuit Curia — my soul was rocked to its core.

When the Holy Father came here to the U.S. last year and said, “Those of you who do not believe, and cannot pray — send me good wishes” — I was never more proud of being a human.

But in the end, I don’t think this worldview colors my approach to the subject so much as my contrarian temperament does. If this story didn’t run counter to what’s widely believed, I doubt I would have been inspired to spend years researching it.

Long before his election to the papacy, Eugenio Pacelli served as papal nuncio to Germany and Vatican Secretary of State. How would you characterize his posture and actions as Hitler slowly rose to power in Germany in the 1920s and 1930s?

As I show in Church of Spies, Pacelli worked secretly to thwart Hitler’s first attempt to seize power, in 1923. The Nazis knew about this and never forgot it.

When Hitler did take power, ten years later, Pope Pius XI was briefly enchanted, I think, by Hitler’s anticommunism. He wanted to give the benefit of the doubt, hoping that Hitler would turn out to be merely a German Mussolini, and realizing, above all, that Hitler had the masses with him. So when Hitler offered the Vatican the chance to sign a concordat with the Reich, guaranteeing Catholic rights, the pope directed Pacelli to negotiate the terms.

It fell to Pacelli also to monitor German compliance with the treaty; and to that end, Pacelli set up an extremely sophisticated episcopal intelligence network, centered in the Archdiocese of Munich-Freising. After Pacelli became Pope Pius XII, this intelligence network played a vital role in the plots to overthrow Hitler.

Some critics see the concordat as an effort to protect the Church’s own interests rather than to look out for the good of all, particularly the Jews. Is this accurate?

It’s not so much accurate or inaccurate, as incomplete.

Recently I spent a week in the archives of the Vatican Secretariat of State, and one of the most striking documents I found was a report from the mid-1930s from Switzerland, from the Zionist Congress, where the Jews were citing the sermons of Munich Cardinal Michael Faulhaber — sermons defending the Old Testament — as proof that the Vatican rejected the Nazi agenda.

So this shows, in my view, that the concordat was not seen at the time by Jewish leaders as something that threw non-Aryans under the bus. Later in the war, you find Protestant resistance-heroes like Dietrich Bonhoeffer lamenting that they didn’t have a concordat; they felt that having some guarantee of their rights would have made them less subject to Nazi pressure.

But it is true is that the Vatican tried to make the best deals it could with the German Government, to protect its interests. That’s something that can be said of every institution in the world that had to deal with Hitler, including the British, French, American and even Soviet governments.

In general, those institutions did not see themselves representing the Jews specifically, or mankind more generally. In my view, in light of the Shoah, that was a tragically limited perspective. But the failure here was not a uniquely Catholic or papal one.

Given the political crisis in Europe and the imminence of war, what role did Eugenio Pacelli’s opposition to Hitler play in his election to the papacy in early 1939?

I don’t think his opposition to Hitler played a great role in Pacelli’s election, as much as his four decades in the Vatican diplomatic service.

For sure, Germany was the only nation in which Pacelli’s election was publicly criticized in the press. But he was on all sides considered the total personification of responsibility — discretion and prudence, especially in speech. His predecessor, Pius XI, had been somewhat impulsive, and Pacelli was seen as one who could calm the waters.

With Europe on the brink of war, the cardinals needed someone who could be trusted at the rudder of the ship — a steady hand — and in that respect, Pacelli had no peer.

Pope Pius XII was on record opposing Hitler and defending the Jews, but you report that he was strongly urged to maintain a relative “silence” after the war began. Who were some of these parties, and what was their reasoning?

There were two parties who advised him to keep silent — the German bishops, and the German military resistance.

The German bishops, as Vatican transcripts show, urged Pius XII to dial back public criticism of the Nazis, because a 1937 encyclical attacking Nazi neopaganism had worsened the plight of the German Church. So Pius XII agreed to modulate Rome’s public criticism of Germany.

Later, as papers in the Franklin Roosevelt Library show, the German military resistance asked Pius XII to mute public criticism, because they feared a crackdown on the ecclesiastical intelligence network that had become part of the anti-Hitler plots.

For instance, criticism of the Nazis by the exiled German Jesuit Father Friedrich Muckermann led directly, in 1941, to the arrests of two Vatican intelligence agents involved in resistance work — a Jewish journalist, Theresa Schneidhuber, and Monsignor Johannes Neuhausler, the deputy of Munich Cardinal Michael Faulhaber. Neuhausler spent the war in Dachau; Frau Schneidhuber died in the concentration camp at Theresienstadt.

Without that counsel, do you believe Pius XII might have spoken out more explicitly in opposition to Hitler and Fascism?

In the case of a counterfactual, one can never know what “would” have happened. But, I think that the urging of these sources tipped Pacelli toward a course with which he was temperamentally comfortable.

Pacelli had spent most of his adult life practicing the art of backstairs diplomacy, and the Church itself had honed this art over nearly two millennia of conflict between Church and State, in which the papacy usually held the weaker hand.

The time had long passed when a pontiff could effectively undermine a secular leader by calling down on him the threat of damnation. When Pius IX had tried this, in the 19th century, Europeans had laughed him out of court; and the prestige of the papacy had suffered greatly as a result.

I think that Pius XII was afraid that if he called for a kind of moral crusade against Hitler, Protestant Germans — and even many Catholic Germans —would have rallied round Hitler all the more.

I’m reminded here, sadly, of the irate reaction among many professed American Christians to Pope Francis’ recent words at the Mexican border. The presidential candidate in question, who complained that he was implicitly criticized, didn’t find his standing eroded at all.

Gerald Korson, a career Catholic editor and journalist, writes from Indiana. He was editor of Our Sunday Visitor from 2000 to 2007.