To read the Italian press, one would think that this Thursday marks the definitive end of a papal era. As of that day, Castel Gandolfo, the summer residence of popes for the last four centuries, will become a museum, with almost all of the historic palazzo thrown open to visitors.

The suggestion has been that from this point forward, no pope will ever again reside on the grounds of what was once a residence of the Roman Emperor Domitian, and which actually has a larger total footprint in terms of the surrounding grounds than the Vatican itself.

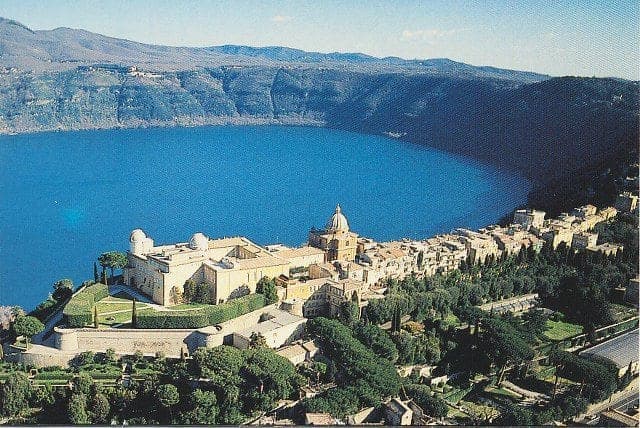

The complex is about a half-hour outside Rome, depending on traffic, and boasts a jaw-dropping view of Lake Albano. Because it’s higher up, the air is cooler and fresher, making it a destination of choice during sweltering and muggy Roman summers.

The papal palace was built under Pope Urban VIII in the 17th century, and has been used by almost every pope since for their summer vacations, except for the interlude between 1870 and 1929 when popes had declared themselves “prisoners of the Vatican” after the loss of the Papal States.

In reality, the “end of an era” rhetoric is overheated. It’s simply not the case that just because Francis has opted to shun the traditional summer retreat, future popes are obligated to follow his lead.

As a fundamental matter of Church law, one pope cannot bind the hands of his successors. That, for instance, is why a pope may freely choose to resign himself, but he cannot make resignation mandatory – or, if he tried, another pope could simply undo the mandate.

Under the Code of Canon Law, a pope has “full, supreme, immediate and universal” authority, which essentially means that no one can tell him what to do.

Further, to suggest that some aspect of practice or tradition will “never” see the light of day again betrays a misunderstanding of how Catholicism operates.

The Catholic Church, as Auxiliary Bishop Robert Barron of Los Angeles likes to say, is sort of like your grandmother’s attic – stuff may be mothballed up there for a long time, and people often forget it’s even there, until one day there’s a sudden perceived need for one of those things and it gets hauled down again.

After the Second Vatican Council in the mid-1960s, for instance, many observers confidently predicted that before long the Mass would “never” be celebrated in Latin again, after the generation that grew up with it had passed from the scene.

Instead, communities devoted to the older Mass kept it alive until emeritus Pope Benedict XVI brought it down from the attic on a grander scale with his 2007 apostolic letter Summorum Pontificum, establishing the pre-Vatican II Mass as an “extraordinary form” of the liturgy.

Granted, some revivals are probably a bit more likely than others, at least given things as they stand.

It’s easier, for instance, to imagine a future pope deciding to go back to living in the Apostolic Palace, for instance, than it is dusting off the sedia gestatoria, the portable throne with which pontiffs used to be ported into their audiences, and it’s certainly more plausible than a future pope restoring use of the papal guillotine.

(Just in case, however, the last functioning papal guillotine is preserved in perfect working order in a small museum operated by the Italian Ministry of Justice on Rome’s Via Giulia.)

On the scale of likelihood, a comeback for Castel Gandolfo under a future pope probably isn’t that bad of a bet.

John Paul II liked Castel Gandolfo so much he had an Olympic-sized swimming pool installed; Benedict XVI was so fond of the place that it’s where he retreated after he retired in February 2013. Anyone who’s ever spent a relaxing few hours there on a hot summer day, sitting on the balcony of one of the restaurants that jut out over the lake and enjoying a glass of chilled prosecco and some peace and quiet, can understand the attraction.

To date Francis hasn’t spent a single night in Castel Gandolfo, and after Thursday it seems probable he never will. That, however, by no means rules out the possibility that a future pope will do so.

Moreover, one could actually make a fairly persuasive social justice argument that popes passing some time in Castel Gandolfo would actually be a way of giving the little guy a break. The fact that Francis has declined to stay there has dealt a devastating blow to the small town’s bars, restaurants, hotels and shops, the impact of which has been felt much more by working stiffs than by the rich and mighty.

Certainly, expanding the palace’s function as a museum likely will draw more tourist traffic, which will be good for local business, but it’s hardly the same thing as having the star of the show in town on a regular basis.

For now, Castel Gandolfo is probably on the must-see list for Catholic visitors to Rome, a space in which one can roam and contemplate the vicissitudes of the papal past.

Knowing how the Church works, however, it’s also a poignant reminder that in Catholicism, the past is not only never really dead, it’s often not even past.