ROME – Speaking to artists at the Vatican in late November 2009, Pope Benedict XVI emphasized how beauty should not be something illusory or deceitful, but rather something that “gives us wings,” and sometimes even “disturbs us” and leads to suffering.

Quoting the Greek philosopher Plato, he said that the principal effect of beauty, as seen through art, should be to give the viewer a healthy “shock.”

Jacopo Cardillo, an Italian sculptor of international fame whose art name is Jago, definitely took this definition to a whole new level when he decided recently to “undress” Benedict XVI and portray him shirtless instead of dressed in the usual papal regalia.

Ever since, the technically remarkable sculpture has been the object of both criticism and praise, with some viewing it as desecrating the image of the emeritus pontiff while others judge it as an honest portrayal. For Jago, the work of art was never meant to be “derisive,” but rather a celebration of Benedict XVI, whom he considers to be a model for what every pope should be.

“I consider this man to be the greatest theologian alive,” he told Crux in a phone interview.

Jago’s controversial sculpture and a few of his other artworks are showcased at an exhibit called Habemus Hominem, a play on the Habemus Papam uttered at the election of a pope, at the Carlo Bilotti Aranciera Museum in Rome’s scenic Villa Borghese gardens.

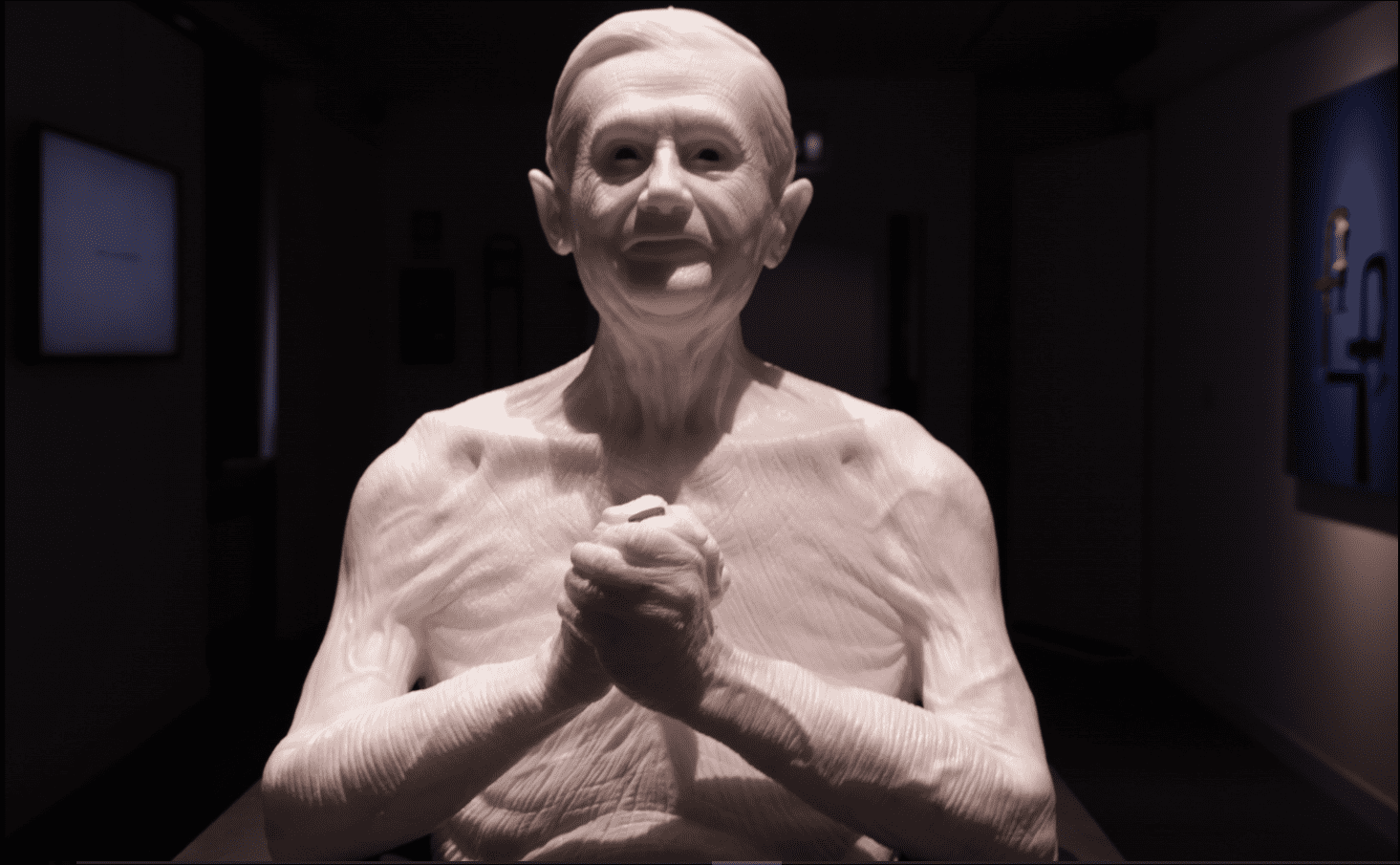

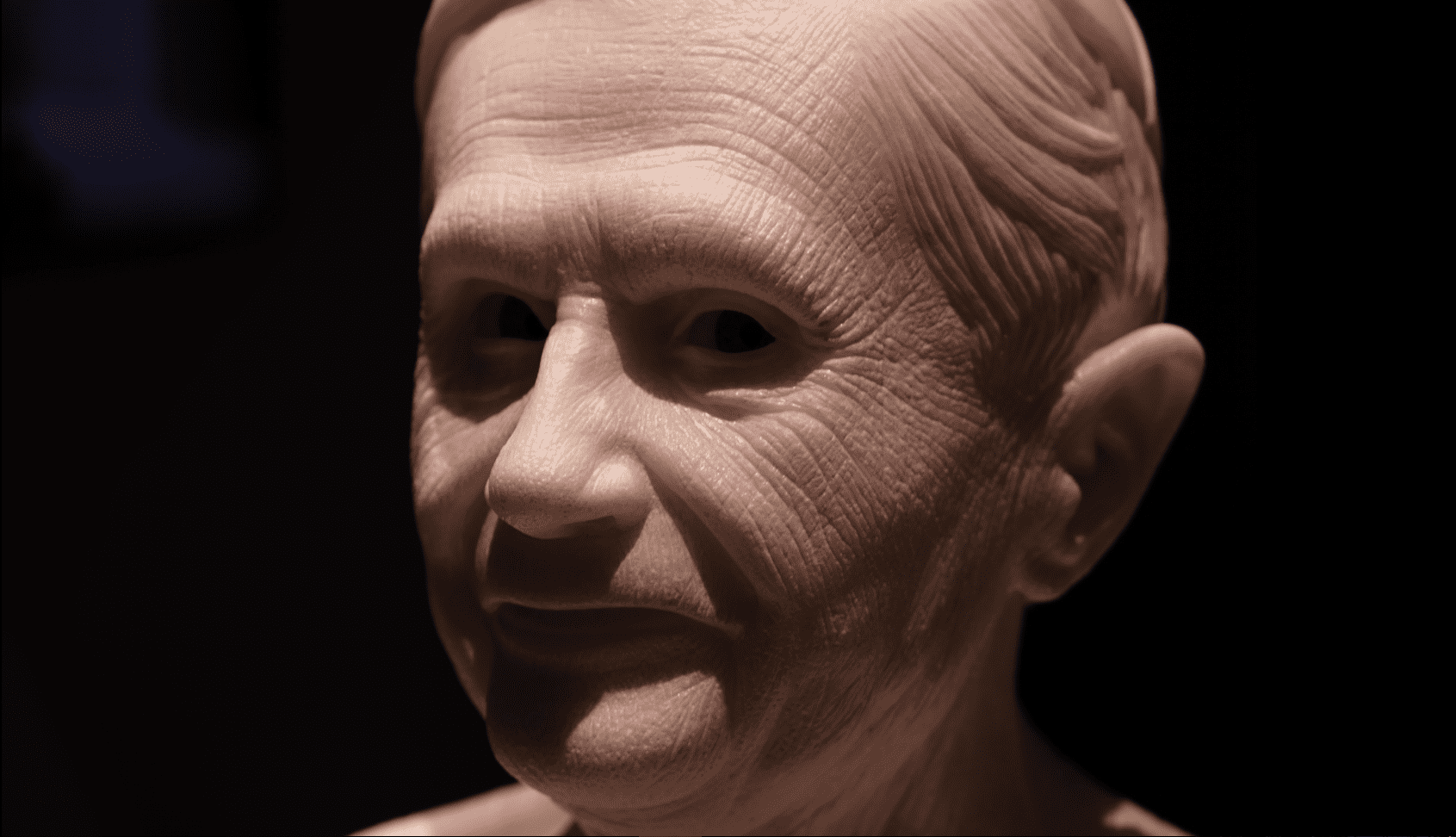

The naked bust of Benedict XVI sits in an unadorned room, a white light shining over it heavily marking the deep wrinkles on his face and chest, as he holds his hands tightly together with a look of serene resignation.

“Perhaps, it’s the first time we get to see him for who he really is, represented in his humanity and without the clothes he always wears,” said a senior high school student who had come to see the show with her class as a part of the art history lesson.

“He’s unmasked from his uniform,” said another young girl dressed in the Nazareth high school uniform. “Beyond the story, the concept is really beautiful,” a classmate remarked.

The story of the Benedict bust starts in 2009, when Jago was commissioned to create a likeness of the pope. The finished piece, which was cloaked with the papal garments, garnered a discreet success, winning several awards and positive critiques.

“The pope himself wrote saying that he wanted to award me with the pontifical medal for the sculpture,” Jago said. Italian Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi, President of the Pontifical Council for Culture, awarded him with the medal in 2012.

“That work became in a way a relic, something that you would hold dear, but for me that attachment had become unbearable, in the sense that the work did not represent me that much as far as its realization,” Jago said.

“When you are really emotionally attached to that object, intervening again and destroying it means destroying that attachment. And so it was.”

On February 11, 2013 Benedict XVI announced that he would step down from his role as pope, shocking the Catholic community and the world. That day Jago was wrapping up his first solo exhibition promoted by the celebrated, albeit somewhat controversial, Italian art historian Vittorio Sgarbi, when his father told him the news.

His father used the term “uncloaked” or “stripped” to describe what had happened, giving Jago the final nudge to revisit his masterpiece. He took his tools and began chafing away at the stone, carving out from underneath the heavy garments the naked and fragile skin of the emeritus pope.

“That day I decided to intervene and modify it, but not in an derisive way,” Jago said, and he chose to keep every fragment that came off the original. “The weight of those clothes, of that habit, I still keep today. I have every scrap and dust that were produced, it did not go to waste,” he said.

The artist chose to leave only two elements, the papalina, the traditional white skullcap worn by the popes and the fisherman’s ring, or St. Peter’s ring, unique to every pontificate.

“I did that because a pope does not retrocede, he can’t say ‘I can no longer be pope, I’ll go back to being a cardinal.’ No, the pope is the pope because the journey he started cannot be canceled,” Jago said.

The work was finished in 2016, but the artist’s interest in Benedict goes back long before this particular piece. Jago is a Catholic, born in the central Italian town of Frosinone, who carries a cross around his neck at all times, and whose father shares a birthday with Benedict.

“I remember that when he was interviewed, even as a cardinal, he did not speak of religion but of spirituality, he could be all-encompassing in such a simple way and speak to everyone,” he said. “This is what a pope should do, communicate to everyone.”

In the eyes of the artist, Benedict’s abdication from the pontificate “made him even more human” and relatable, something that he wished to reflect in his statue that he hopes will serve as testament to that historic moment.

He describes the sculpture as “a celebration of the body,” something that in Jago’s opinion all human beings wear, making us all the same.

A startling aspect of the marble likeness of the pope is the eyes, which seem to follow the viewer from every standpoint. Initially the statue had no eyes, a nod to the Italian sculptor Adolfo Wildt, who just like in classical bronze statues chose not to put eyes in his works.

Only after Benedict stepped down as pope did Jago decide to give his statue sight. He painted inside the inverted semi-spheres that made the eye sockets, resulting in the unexpected illusion that Benedict’s gaze follows viewers around the room.

“It opened a world for me and it became today a bit of a trademark,” the artist said. “As a viewer, I go to an art show and I look at artwork. What happens if the work of art looks at you?”

“It means that you also are artwork,” Jago said.

He referenced a young man he knows suffering with multiple sclerosis, a degenerative disease that slowly impairs movement, noting that the last parts of the body that can still move are the eyes.

“That is the final and most important element that allows you to recognize that a person is alive. That he’s there,” Jago said.

In the same way, the eyes show that “[Benedict] is there in that moment. He’s there, he’s present. He’s a living statue,” he added.

With his 240,000 followers on Facebook, Jago is considered a ‘social artist,’ frequently posting pictures and videos on his social media page. One of these videos is the story of the creation and “stripping” of the bust of Benedict, which has been viewed more than 15 million times.

“Every frame of our existence is a masterpiece. Today we have the instruments to keep track of this and it’s something very precious,” Jago said. “Every single moment in the realization process of our work of life is artwork.”

For the artist, the pontiff has an important role in fostering and promoting beauty and currently “it’s the right moment to bring back something that we are losing.”

“Looking at Rome, we live in a moment of total conservation [of art]. But what are we adding?” Jago asked. “Once the popes, despite the criticisms of nepotism etc., were people concerned with creating beauty. Those things that we are proud of today.”

He longs for the popes to return to this crucial role, though he recognizes that it’s important that they maintain an image of humility. When asked if he would make a portrait of Pope Francis, he answered “Why not? of course.”

But the artist also said he would impose three fundamental conditions: That it be commissioned by the Vatican, that it be sincerely desired and, most of all, that he may be allowed to do whatever he pleases.

Popes have longstanding experience of dealing with capricious artists, from Michelangelo to Caravaggio, but history also suggests that often enough, the prize for putting up with a little heartburn is easily worth it.