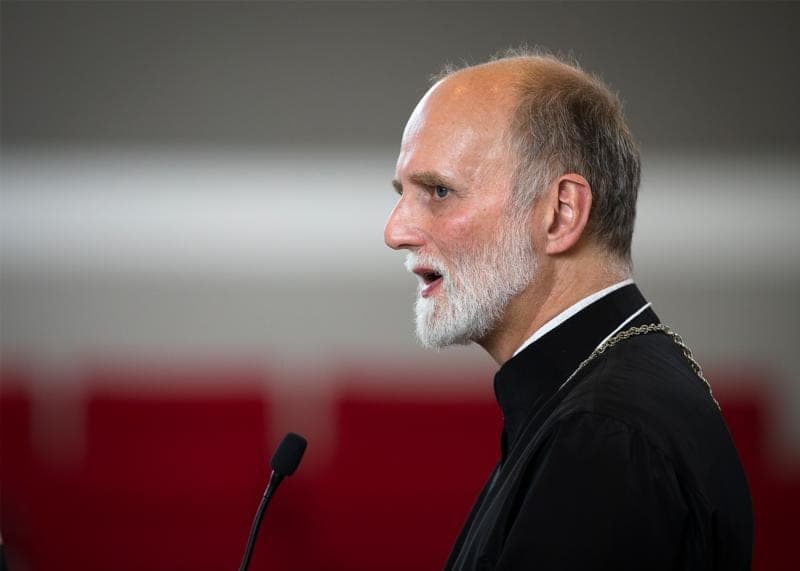

ROME – Archbishop Borys Gudziak, one of nearly 50 Ukrainian Greek Catholic bishops in Rome this week, says he and his fellow prelates are pushing harder than ever for a papal visit to Ukraine – a trip that he said is crucial to ending conflict in the country, but which is being held up by fear of potential reprisal from Russia.

Speaking of the ongoing conflict with Russian troops in Ukraine’s eastern region, Gudziak – who heads the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia – lamented that yet another life was taken this week when a barrage of 17 missiles let loose in the conflict area.

“Almost every day someone is killed. This has been going on for five years. It’s like a terrorist act in your country every day. This is thousands of terrorist acts,” he told Crux.

“We believe that if the pope came to Ukraine, the killing would, if not stop, would lessen,” the archbishop said, explaining that an invitation for a papal visit was issued a long time ago.

Gudziak said the delay in accepting the invite is due at least in part to fear over backlash from the Russian Orthodox Church, despite the pope’s consistent attention to Ukraine and his frequent appeals for an end to the ongoing war with Russian separatists.

“The opinion of Moscow regarding anything significant in the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church has been a shadow over us for at least 50 years, since the mid-1960s,” Gudziak said, explaining that fear of blowback from the Russian Orthodox definitely has “a role” in why a papal visit to Ukraine has yet to take place.

Tensions between the Russian Orthodox and Greek Catholics in Ukraine have been growing worse since the fall of communism in the Soviet Union in 1991. After Ukraine became independent from the USSR, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church asked for its properties to be returned; however, many had been given by the communist regime to the Orthodox Church, which refused to give them back.

The situation was made more precarious earlier this year, when the Patriarch of Constantinople recognized the independence of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, a move Moscow refuses to recognize. The Russian Orthodox Church accuses the Greek Catholics of supporting the split.

Gudziak said he is using the occasion of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church’s Sept. 2-10 synod, which is taking place in Rome, to raise the issue of a papal visit with the Vatican officials they meet again after a two-day meeting between Ukrainian bishops and Vatican officials in July.

“One of the great opportunities we had for two days is to explain things, to bring things home, make them concrete with life stories,” he said, adding that the meeting was “really a special occasion to give information helpful for the discernment process,” and they intend to build on that in the synod.

“There is nobody, no institution has assisted Ukrainians internationally in the last 100 years as much as the Holy See,” he said, explaining that although there has been no word yet about a papal visit, “we have signals that it’s not out of the question.”

This week’s synod has brought together 47 Ukrainian Greek Catholic bishops from all over the world, and is focused on the theme, “Communion and unity in the life and testimony of the Ukrainian Church today.”

The synod has drawn the participation from top clerics and Vatican officials, including a private audience with Francis himself, as well as Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Pietro Parolin; Cardinal Leonardo Sandri, prefect of the Vatican Congregation for Eastern Churches; and close papal ally Cardinal Angelo de Donatis, Vicar of Rome.

RELATED: Synods are not for deal-making, but for listening to Spirit, pope says

In July, Francis also named de Donatis apostolic administrator of the new exarchate for Ukrainian Greek Catholics living in Italy, which has become a prime destination for those fleeing poverty and war in their homeland.

In his comments to Crux, Gudziak explained that while the Ukrainian Greek Catholic bishops typically hold their synods in Ukraine, the reason this year’s gathering is happening in Rome is because of the theme of the gathering, which focuses on unity and communion with the See of Peter.

He said he firmly believes that the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church is a priority for the Vatican, as is evidenced by “unprecedented” gestures such as the two-day meeting in July, and a special collection in 2016 which raised over $17 million to offer support to Ukrainians struggling due to the country’s economic crisis and the conflict in its eastern region, some $5 million of which was donated from the pope’s own charities.

“By the war and by Putin’s economic warfare, (Ukraine has) become the poorest country in terms of per capita GDP in Europe. The economy is not doing well,” Gudziak said, explaining that many people are unemployed and some 10 million have left the country over the past two decades.

The ongoing conflict in eastern Ukraine has also left many of its citizens scarred, with hundreds of thousands now suffering from post-traumatic shock, he said. Over 100,000 veterans have already been decommissioned, most of whom suffer psychological trauma due to the war.

According to Gudziak, official numbers put the death toll at 13,000 on the Ukrainian side of the border, however, the number of casualties on the Russian side of the demarcation line, many of whom are Ukrainian citizens, is unknown.

In his Sept. 3 speech to synod participants, Parolin outlined four key challenges the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church is facing in the country: Evangelization, political and social issues, war and ecumenical relations, which have been complicated by the recent independence of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

Gudziak said he believes these challenges in themselves are not necessarily unique to Ukraine, but they have been compounded by the country’s economic crisis and its ongoing war, prompting a crisis of faith in some.

“People who face ultimate challenges often face ultimate questions,” he said.

With Francis’s constant attention to the poor and those on the fringes, Gudziak voiced hope that despite whatever ecumenical backlash might ensue, the pope would come to console his tired and suffering flock in Ukraine.

Gudziak said he thought a papal trip could possibly be scheduled to take place sometime in the next 24 months, saying there are numerous occasions which would provide opportunities for a visit.

“Do I think it will happen? I wouldn’t be surprised if it does,” he said, explaining that he spoke “very passionately” about the significance of a visit to Parolin, who promised to pass the message on to Francis.

“This pope is a pope of unexpected surprises and great affinity to peoples and places that are on the edge, and Ukraine is on the edge of Europe geographically,” he said. “It’s enduring a war, it’s been rendered the poorest country in Europe, it has 10 million migrants outside of the country.”

“We have no doubt that the Holy See is in solidarity with the suffering in Ukraine, particularly with the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church,” he said, but noted that institutionally, there are always hurdles to jump.

“In every big structure there are different points of view on issues and not everyone considers Ukraine as a priority,” he said, explaining that in an exchange with Parolin, he insisted that a global rising of tensions and deconstruction of Catholic structures “allows us to be bold and free.”

“The Holy Father has shown in many ways an incisive, prophetic vision and the courage to bolt from practiced tradition and protocol,” he said. “We would hope that he might move prophetically to contribute to peace in Ukraine with a grand gesture.”

Follow Elise Harris on Twitter: @eharris_it

Crux is dedicated to smart, wired and independent reporting on the Vatican and worldwide Catholic Church. That kind of reporting doesn’t come cheap, and we need your support. You can help Crux by giving a small amount monthly, or with a onetime gift. Please remember, Crux is a for-profit organization, so contributions are not tax-deductible.