ROME — “I understood we were all like dogs. They told us to sit and we sat, to get up and we got up, to roll over and we rolled over,” said an Australia-born religious identified only as “Sister Elizabeth” in the book, “Veil of Silence.”

After 30 years in religious life, she said she realizes she, too, had treated younger members of the congregation that way.

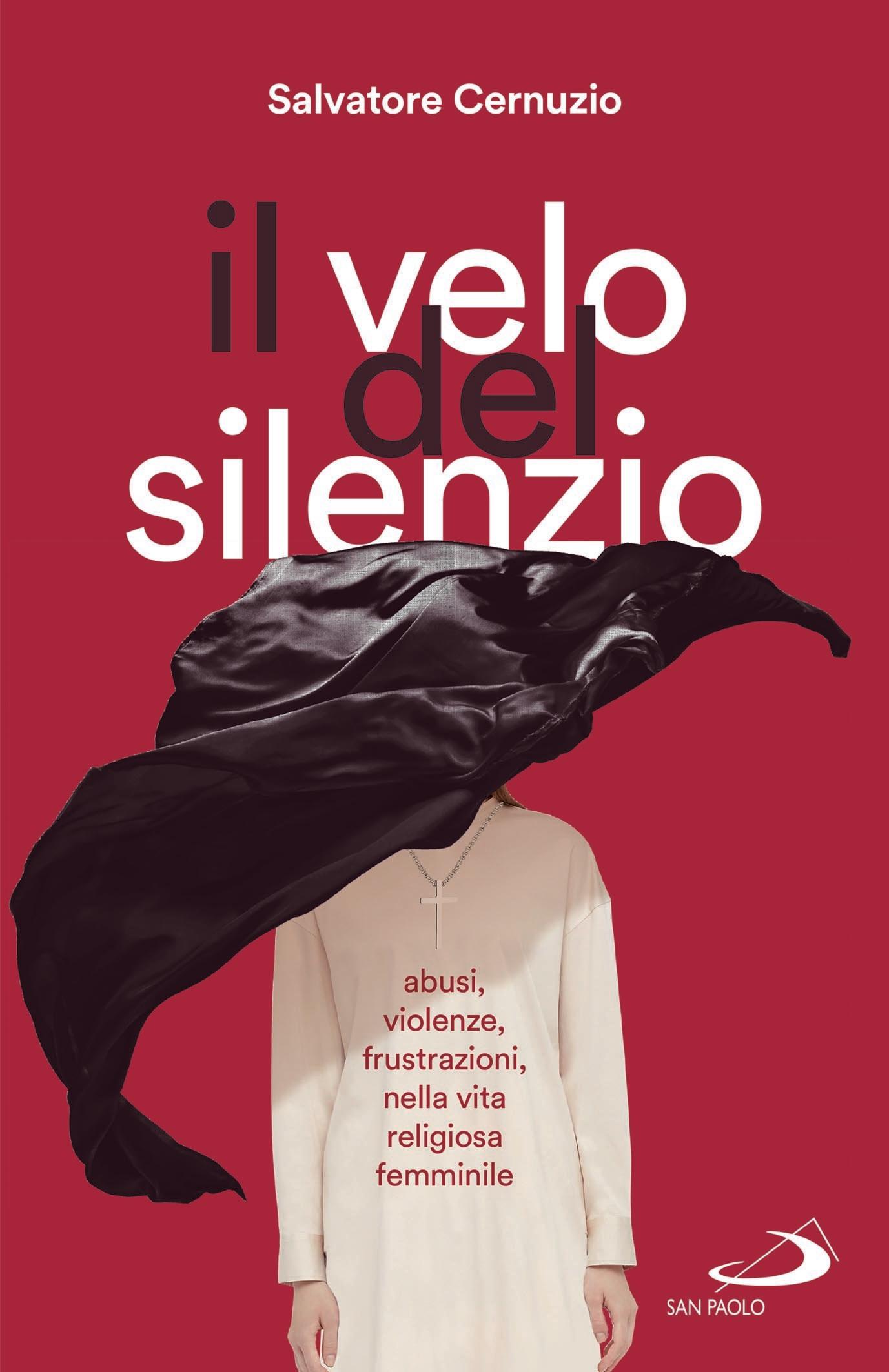

“Many still use that abusive behavior that has been passed down from generation to generation,” she told Salvatore Cernuzio, a journalist and author of “Il Velo del Silenzio” (“Veil of Silence”), a book in Italian that was scheduled for publication Nov. 23.

In an author’s note Cernuzio writes of a surprise meeting with a childhood friend who had joined a cloistered community of nuns; 10 years later, a “tribunal” of older sisters decided she did not have a vocation and sent her packing.

That encounter, he said, came just a few days after La Civiltà Cattolica published an article by Jesuit Father Giovanni Cucci, a professor of psychology and philosophy at Rome’s Pontifical Gregorian University, calling for greater church attention to psychological and physical abuse in communities of women religious.

While his childhood friend was still too upset to talk about her experience, even a year after leaving the convent, Cernuzio wrote, he set out to speak to women willing to share their stories. The book includes interviews with 11 women; one was sexually assaulted by a priest but was told by her superiors that she must have led him on. The others recount abuses of power and psychological or emotional abuse, mainly through acts of cruelty, humiliation and a denial of medical or psychological assistance.

Several of them mention how, particularly in the novitiate, they were required to ask permission to do or to have anything — including to take a shower or to have sanitary products during their menstrual cycle.

Sister Aleksandra, who told Cernuzio about being abused by a priest, said she is looking for a way out of her community.

“I don’t know where I’ll go, I just want to follow Jesus, and it’s not possible here. I can’t live in this situation anymore and I’m afraid of destroying my physical, psychological and spiritual health. I hope to find help, maybe from some laypeople because I know that my congregation doesn’t care about me,” she said. “As I have heard so many times: the fault is always with the one who leaves.”

In the book’s introduction, Cucci said that the stories of the 11 women have several things in common, but especially the tendency in some more traditional orders to keep the same superior or superiors in office for decades, which can lead them to “confuse their will with the will of God” for the sisters in their community.

They also confuse uniformity with the unity of or peace within the community and treat any form of questioning as not only a challenge to the superior, but as a rejection of God’s will.

The stories, especially that of Sister Aleksandra, also show how slow the church is to change the way it deals with sexual abuse. “‘Safeguarding’ the good name of the institute is the priority, sacrificing the victim. The abused religious is transferred after being accused of seducing the priest and the priest stays in place, continuing his predatory activity undisturbed.”

In the book’s preface, Xavière Missionary Sister Nathalie Becquart, one of two undersecretaries of the Synod of Bishops, said the church must listen to the victims of such abuse and acknowledge that “consecrated life in all its diversity, like any reality in the church, can generate both the best or the worst” in people.

Religious life is at its best “when the vows of poverty, chastity and obedience are proposed as a path of human and spiritual growth, a journey of maturation that makes people’s freedom grow because authority is called to promote the dignity of the person,” she wrote. “The worst is when the religious vows are interpreted and implemented in a way that infantilizes, oppresses or even manipulates and destroys people.”

“The entire church,” she said, must come to grips with “a culture saturated with clericalism” and “forms of authority permeated with various types of abuse.”

The solution, Becquart said, is to adopt what Pope Francis has described as a model of a “synodal church” where every baptized person is respected, listened to and takes responsibility for caring for one another and being missionaries in the world.