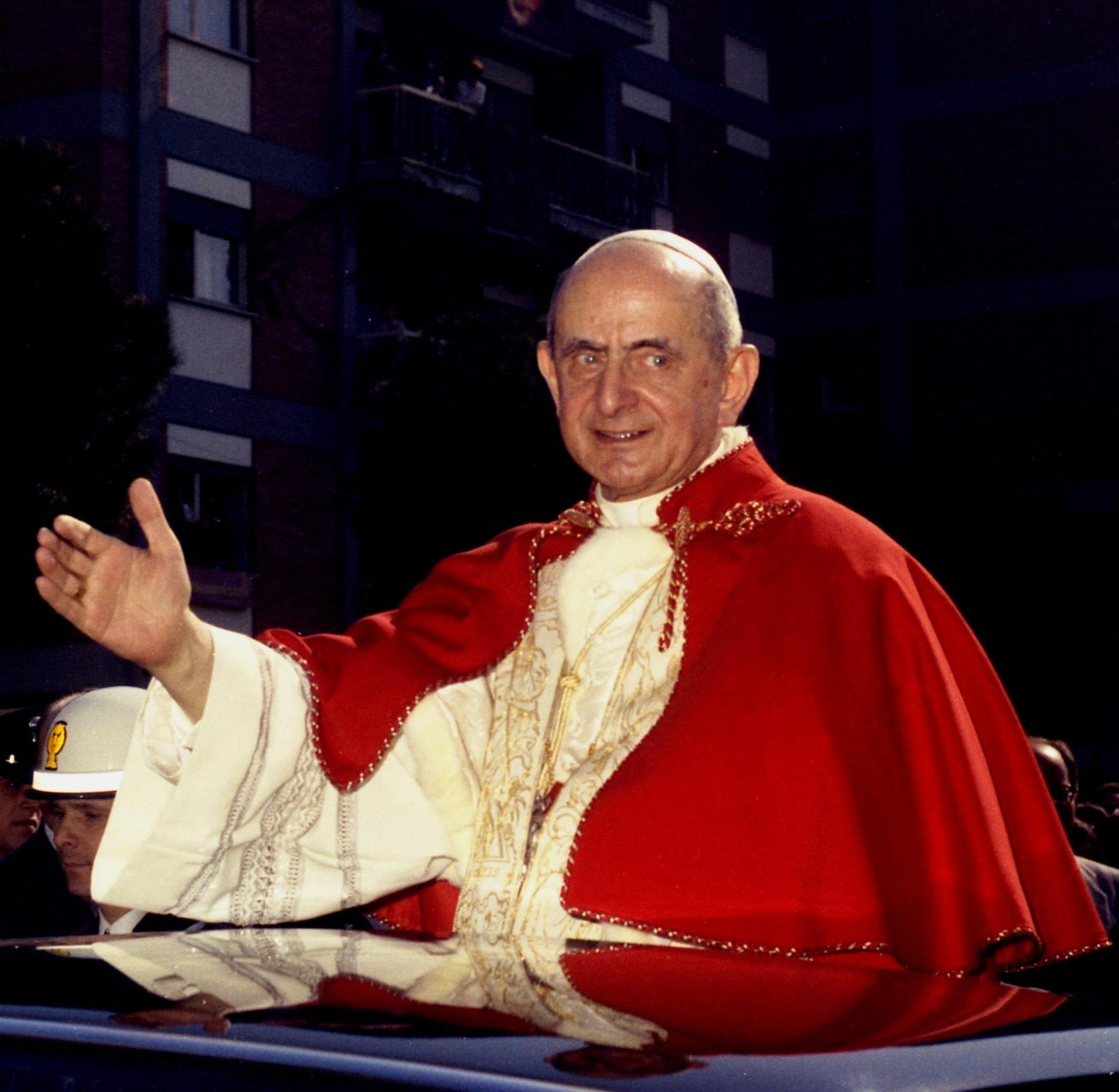

Today marks the 38th anniversary of the death of Blessed Pope Paul VI on August 6, 1978, and to mark the occasion, the news site of the Archdiocese of Milan, which was led by then-Cardinal Giovanni Battista Montini from 1954 to 1963, published a talk he gave right after the death of St. Pope John XXIII in which he predicted the election of a non-Italian pontiff.

“There’s never been as much of a probability as in this hour of the Church that the pope will be a non-Italian,” Montini said. “And there would be nothing strange about it. Ecumenism is carrying us this way, no?”

“Maybe the hour is mature for us to feel like brothers with one who isn’t of our language and our country,” he said.

It didn’t happen in 1963, of course … instead, the cardinals elected the very Italian who issued that prophecy. Fifteen years later, however, Montini’s forecast was realized with the election of a Polish pope, followed by a German and now an Argentine.

Pope Francis approved Paul’s beatification in October 2014, and there has been speculation that Francis might dispense with the requirement of a second miracle to declare Paul a saint, technically known as an “equipollent” canonization, as he did with John XXIII, the other pope of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65).

So far that hasn’t happened, and in the meantime a miracle claim is under investigation involving the healing of a young music teacher and viola player from a brain tumor, whose father had placed a photo of his ailing son in the arms of a statue of Paul VI in Milan’s Sanctuary of Saint Mary of the Graces.

If Francis does end up canonizing Paul, there would be something fitting about him being the pope to do it, because in many ways the papacies of Paul VI and Francis are eerily similar.

I say “papacies” rather than “popes” because in terms of personalities, Montini and Jorge Mario Bergoglio are a study in contrasts – Montini was a man of deep elegance and culture, at times a bit aloof and even ethereal, while Bergoglio, though no slouch in the culture department, is nevertheless more down-to-earth and populist.

Certainly few would have accused Montini of radiating warmth and a common touch quite like Bergoglio does.

Nevertheless, both Paul VI and Francis are seen as reformers, both presided over raucous and high-profile summits of bishops, both are generally perceived as favorable to the center-left constituency in the Church, and both seem to see more progressive figures in the episcopacy as their key allies.

One could make a good argument that what giants such as Cardinals Giacomo Lercaro of Bologna, Franz König of Vienna and Leo Joseph Suenens of Brussels were to Paul VI, today figures such as Cardinals Reinhard Marx of Munich, Christoph Schönborn of Vienna and Oscar Rodriguez Maradiaga of Tegucigalpa, Honduras, are to Francis.

Just as Lercaro, König and Suenens were perceived to have Paul’s backing at Vatican II to push forward a reform agenda, Marx, Schönborn and Rodriguez, in tandem with others such as Italian Archbishop Bruno Forte, were seen as having Francis’ encouragement in doing the same thing at his two Synods of Bishops on the family.

Of course, the conventional perception is that Paul’s moderate reform effort brought him a lot of grief, in large part because he often managed to make everyone at least a little upset.

The Catholic right never really forgave him for not keeping Vatican II under tighter control, especially on matters such as changes in the liturgy, while the left can’t get past his “no” to artificial birth control in the 1968 encyclical Humanae Vitae.

To some extent, Francis faces an analogous situation, meaning he draws some fire from both sides of the aisle.

Earlier this week, for instance, at the same moment many Catholic liberals were applauding when he named a longtime advocate for the ordination of women as deacons to a new commission to study the issue, the pro-LGBT group DignityUSA denounced his recent remarks on gender identity to Polish bishops for fomenting “increased violence towards, and oppression of, transgender and gender-nonconforming people.”

(In a Q&A session with bishops during his trip to Poland, Francis decried what he saw as the “ideological colonization” of wealthy countries trying to force others to teach children “that everyone can choose their gender,” describing it as “terrible.”)

For the most part, however, the Catholic left is still enthusiastic about Francis, if anything wishing he would be more aggressive about compelling other bishops to fall into line with his vision.

Will there be a Humanae Vitae moment for Francis, which puts him in the same awkward spot long occupied by Paul VI?

Some thought it might come with his decision on Communion for divorced and remarried Catholics at the conclusion of the two synods, but Francis in that case deftly managed to thread the needle – certainly not delivering a firm “no,” but making his apparent “maybe” sufficiently nuanced and qualified that everyone can read it in their own way.

Perhaps it will come with the commission on women deacons, if his eventual answer is “no,” and given his views on the risk of clericalizing women that’s not an implausible result – although it’s hard to imagine whatever he decides on that front would have the same vast cultural echo as rejecting the pill right at the peak of the sexual revolution in the late 1960s.

More broadly, Francis has a form of insulation that Paul VI didn’t enjoy in quite the same way, which is his broad popularity outside the chattering classes. As a friend of mine and longtime Vatican-watcher puts it, “He just makes people feel good.”

However things play out, the bottom line is that there’s more than a little Paul VI in Francis.

Perhaps the current non-Italian pope Montini anticipated all those years ago may spend some time today, on the anniversary of Paul’s death, pondering the vicissitudes of his remarkable, but also often embattled, predecessor.