ROME – These days, few would deny there’s such a thing as anti-Christian persecution. From the genocide in Iraq and Syria, labeled as such by both the U.S. State Department and Pope Francis, to the recent bombing of the main Coptic cathedral in Cairo and Boko Haram-fueled slaughter in Nigeria, the evidence is simply too overwhelming.

This week, U.S. Rep. Chris Smith of New Jersey led a delegation to Erbil in Iraq to meet Christians living in refugee camps who have fled ISIS, in an effort to spotlight what he sees as failures by the Obama administration to assist them.

After meeting with Christian families and clergy, as well as officials from the U.S., other states and the U.N., Smith said, “This Christmas season, the survival of Christians in Iraq, where they have lived for almost 2,000 years, is at stake.”

Smith said he intends to go back to Washington to prod Congress and the incoming Trump administration to target more aid specifically to Christians and to other religious minorities.

Yet even if the reality can no longer be dismissed, there are other forms of denial that often allow people to justify keeping anti-Christian persecution on a back burner. One of the most persistent, and pernicious forms it takes is the idea that Christians have somehow brought this backlash on themselves.

The historical variant of the idea is that due to the Crusades, the Wars of Religion, the Inquisition, Christian anti-Semitism, and related chapters of the past, Christianity has long bred violence, either against fellow Christians or followers of other religions, and so today Christians are simply reaping what they themselves have sown.

In the here-and-now, the “it’s their own fault” reading of anti-Christian persecution often focuses on alleged gender inequities within Christianity, as well as the Church’s teaching on matters such as homosexuality and same-sex marriage. A religion that systematically discriminates against whole classes of people, according to this reading of events, shouldn’t be surprised when frustration and anger come home to roost.

Whatever merit those critiques may have, the problem with bringing them to bear on contemporary anti-Christian persecution is that the wrong people end up carrying the blame.

First of all, episodes such as the Crusades and the Inquisition belong to the history of the West as well as that of Christianity, while two-thirds of the 2.3 billion Christians in the world today are non-Western. They live in Africa, in Asia, in Latin America, in the Pacific Islands, even in parts of the Middle East, and even their most remote ancestors had absolutely nothing to do with the sack of Jerusalem by Crusader armies in 1099 or the 17th century trial against Galileo.

Elsewhere on the Crux site today, our India correspondent Nirmala Carvalho has a story about plans by Cardinal Oswald Gracias of Mumbai to celebrate Christmas with the country’s “Tribals,” meaning members of historically marginalized and abandoned indigenous groups who have converted to Catholicism.

What in God’s name, one might legitimately wonder, do these people have to do with what happened in Rome or Spain four centuries ago during the era of the Inquisition?

Likewise in the present, whatever beefs one may have with the role of institutional Christianity in the contemporary Western wars of culture, they have nothing to do with the flesh-and-blood Christians living in, say, Bangladesh, or Malawi, or pockets of the Amazon rainforest in Brazil.

For some time, a major stumbling block to perceptions of the staggering global scale of anti-Christian persecution has been that many Westerners are stuck with an outdated narrative about Christianity.

Statistically speaking, the typical Christian in the early 21st century is not an affluent American male driving an SUV to his megachurch in the Dallas suburbs; it’s an impoverished, likely illiterate African female with a family of six, walking considerable distances through the bush to get to her ramshackle Catholic or Pentecostal place of worship.

Even if one chooses to regard that woman’s religiosity as primitive or dubious, the one thing she certainly is not is responsible for the chapters of Christianity’s past and present which critics often point to as explaining the violence that Christianity sometimes attracts.

What we need, in other words, is the capacity to make distinctions.

In the discussion over anti-Christian persecution, some observers fear that too much emphasis on the suffering of Christians in places such as Iraq, Syria and elsewhere will take the edge off their objections to aspects of Christianity in the West, or will serve to provide cover for teachings those critics regard as objectionable, such as the Catholic Church’s stance on abortion, birth control, women priests, and other matters.

We have to be able to say, “Let those debates go on, but in the meantime people who have nothing to do with any of that are getting their teeth kicked in, and they need our help.”

It would be tragic beyond measure if Christians in the developing world, who are today the vast majority of the Christian population, were to be doubly victimized – once for the mere fact of being Christians, and again by Western indifference related to their alleged responsibility for situations to which they’re completely extraneous.

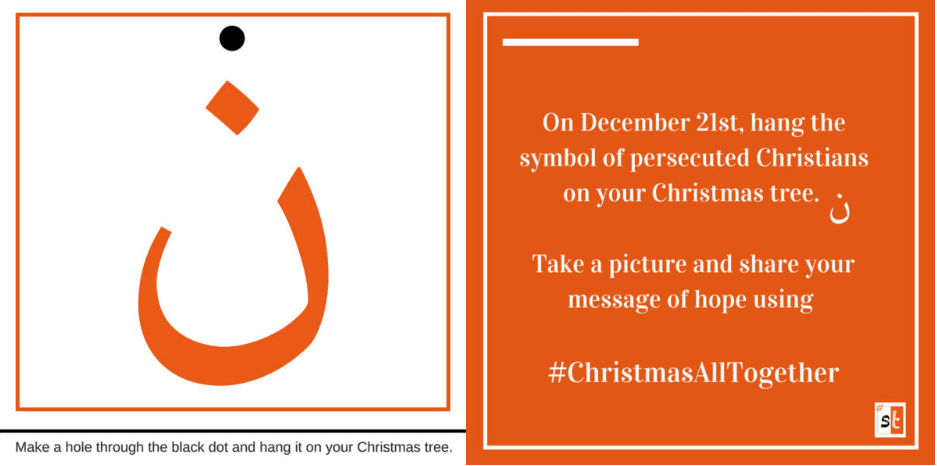

In the meantime, here’s one concrete thing to do to express concern: Follow the lead of the #StandTogether initiative, and display a symbol of persecuted Christians on your Christmas tree. The image is comprised of an Arabic character that sounds like “noon” and is the first letter of the word “Nasrani,” or “Nazarenes,” and it’s what ISIS militants spray-painted on the doors and windowsills of Christian institutions and homes marked for destruction in Syria and Iraq.

While it may not change the world overnight, displaying the symbol is nevertheless a powerful way of building consciousness.