SÃO PAULO, Brazil – Cabo Delgado is the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in Mozambique, adding to the problems the region has been suffering over the past three years.

The northernmost region of the African country, on the border with Tanzania, Cabo Delgado province was struck by a cyclone last year, is currently facing epidemics of malaria and cholera, and has a number of districts affected by a conflict between Muslim insurgents and the army. At least 160,00 people have been displaced by the fighting.

In the middle of this maelstrom, the Church is working hard to help.

Mozambique has now 316 confirmed cases of the COVID-19 coronavirus, 146 of them in Cabo Delgado. Safety measures have been imposed by the authorities, but it’s difficult to comply with social distancing, given that many regions have been flooded with refugees from the districts impacted by the war.

RELATED: Aid workers struggle to reunite kids, families after Mozambique cyclones

“Here in Pemba [the capital of Cabo Delgado], most families are hosting a lot of people. Houses that used to accommodate 10 people now accommodate 20. People who haven’t been able to flee the war zone are hidden in the bushes, sleeping very close to each other. No one can avoid the infection this way,” said the Brazilian-born Bishop of Pemba, Luiz Fernando Lisboa.

According to Lisboa, who has been an almost lone voice in denouncing the conflict since it began nearly three years ago, the government has been trying to cover up the extent of the fighting.

“Cabo Delgado is very rich in mineral resources, so the government feared disturbing the businesses,” he told Crux.

On Easter Sunday, Pope Francis mentioned the humanitarian crisis in Cabo Delgado, highlighting the problem to the world.

“Since then, the authorities have been more transparent about the war, releasing information on the number of casualties from military operations,” Lisboa added.

The bishop explained that Cabo Delgado has always been a forgotten province, lacking investment and infrastructure. A few years ago, informal miners discovered rubies and other precious stones in the region. Companies also began to exploit natural gas and graphite.

“There are foreign interests in those resources. The combination of extreme poverty, mineral wealth, and fundamentalist groups led to this situation,” he said.

Mozambique has a Christian majority – just over 56 percent of the population – with Muslims making up just under 18 percent, but concentrated in the north of the country.

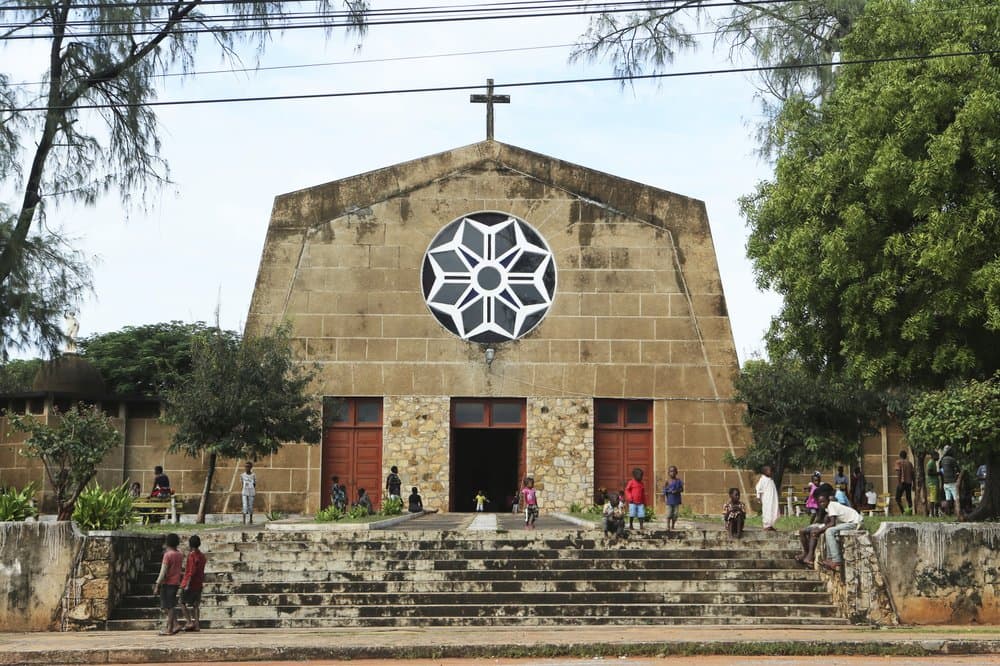

Cabo Delgado has a strong Catholic presence, but Muslims outnumber Christians. According to Lisboa, the two religious communities have always had good relations.

RELATED: Mozambique church a refuge for Muslim cyclone survivors

At the end of April, Mozambique’s government acknowledged for the first time that the insurgency is connected to terrorism, noting that the Islamic State Group has claimed responsibility for several attacks. The terrorist organization started playing a role in the insurgency in 2018 and claimed its first attack on Mozambican security forces the next year.

The terrorist organization usually seize and plunder villages, killing civilians, capturing girls, and persuading young men to join them. About 400 people have been killed by the insurgents since the beginning of their campaign.

“They offer food, money, and clothes to the boys. It’s a reality of great poverty. Many people end up joining them,” Father Pedrinho Secretti, a Brazilian missionary in the district of Namuno, told Crux.

52 residents of Xitaxi village were killed by the insurgents on April 8, possibly after refusing to join them, Lisboa said.

“It’s a strongly Catholic region, so certainly many of them were Catholic. It’s very sad what’s happening,” the bishop explained.

Since the conflict started, the diocese has seen the murder of catechists, members of pastoral commissions, and students at Catholic schools.

In the past few months, the insurgents began targeting Church institutions, including a church and the residence of a group of Tanzanian Benedictine missionaries.

“The missionaries had to hide for two days in the bushes without any food. I decided to send them back to Tanzania and to take all Catholic missionaries out of the nine affected districts,” Lisboa said.

The conflict has caused the suspension of all normal activities in the area, including agriculture. Lisboa now fears that a famine might take place as a result.

The situation was not helped when Cyclone Kenneth hit Mozambique in April 2019. The diocesan Caritas has been working with international organisms in order to provide food, water, and medicine to the local population. It’s also helping to rebuild the houses that were destroyed by the storm.

Meanwhile, outbreaks of cholera and malaria have affected dozens of people in the province and the Church is also active in assisting the sick. “There are so many demands that we feel impotent,” Lisboa said.

COVID-19 entered into the mix of troubles in April, beginning in the region of Afungi, where there’s a natural gas project with a number of foreign employees. The virus spread from there throughout the province.

“The local healthcare system is very precarious. Only one laboratory has been analyzing suspected cases,” Secrett said.

The Church has suspended large gatherings such as public liturgies and is only working with small groups, the priest added.

He is one of the 30 Brazilian missionaries who work in Lisboa’s diocese. With the Mozambicans, the Brazilians share the official language – Portuguese – and the daily experience of violence and poverty.

“But the war is something radically new for us. I’ve never seen anything like this. We’re learning day by day how to deal with that situation,” Lisboa said. He has been Pemba’s bishop for seven years, after spending 12 years as a missionary in the country.

“If COVID-19 grows here as it has in Brazil [currently the third most affected country in the world], it will be a complete tragedy. But, as a matter of fact, the worst virus here is the war. It’s killing much more people,” the bishop said.