YAOUNDÉ, Cameroon – As some traditional communities in Africa are lodging complaints against Christian missionaries of desecration and destruction of their cultures, Catholic leaders find themselves struggling to balance accommodation of local customs and practices against protecting the integrity of the faith.

One front in the mounting tension is Cameroon, where traditional communities have petitioned the Vatican against what they allege is cultural insensitivity and abuses by the Church.

On July 19, the Wimbum people of Cameroon’s North West region petitioned the Dicastery for the Defense of the Faith, complaining that the Catholic Church, in the name of inculturation, is actually desecrating their culture.

The petition accused the church of illegitimately appropriating elements from the community’s secret societies into processions, as well as employing secret masquerades in the church.

“We unequivocally condemn these actions. Our traditions are not mere rituals; they are the lifeblood of our identity, connecting us to our ancestors and shaping our existence,” the petition said.

A similar complaint also came from the people of Nso in Kumbo Diocese, also from Cameroon’s North West region.

In Nigeria, meanwhile, tensions are arising from the opposite direction, among bishops alarmed about what they describe as some priests incorporating “local customs inconsistent with the faith under the umbrella of inculturation.”

According to a leading Catholic observer in Cameroon, the process of inculturation is always a balancing act.

Father Humphrey Tatah Mbuy says inculturation involves “a dynamic relationship between the local church and the culture of its own people, an integration of the Christian experience of a local church into the culture of its people.”

In other words, Mbuy said, the individual churches have the responsibility of first assimilating the essence of the gospel message, studying at the same time the real culture of the people and then initiating a dialogue between the two.”

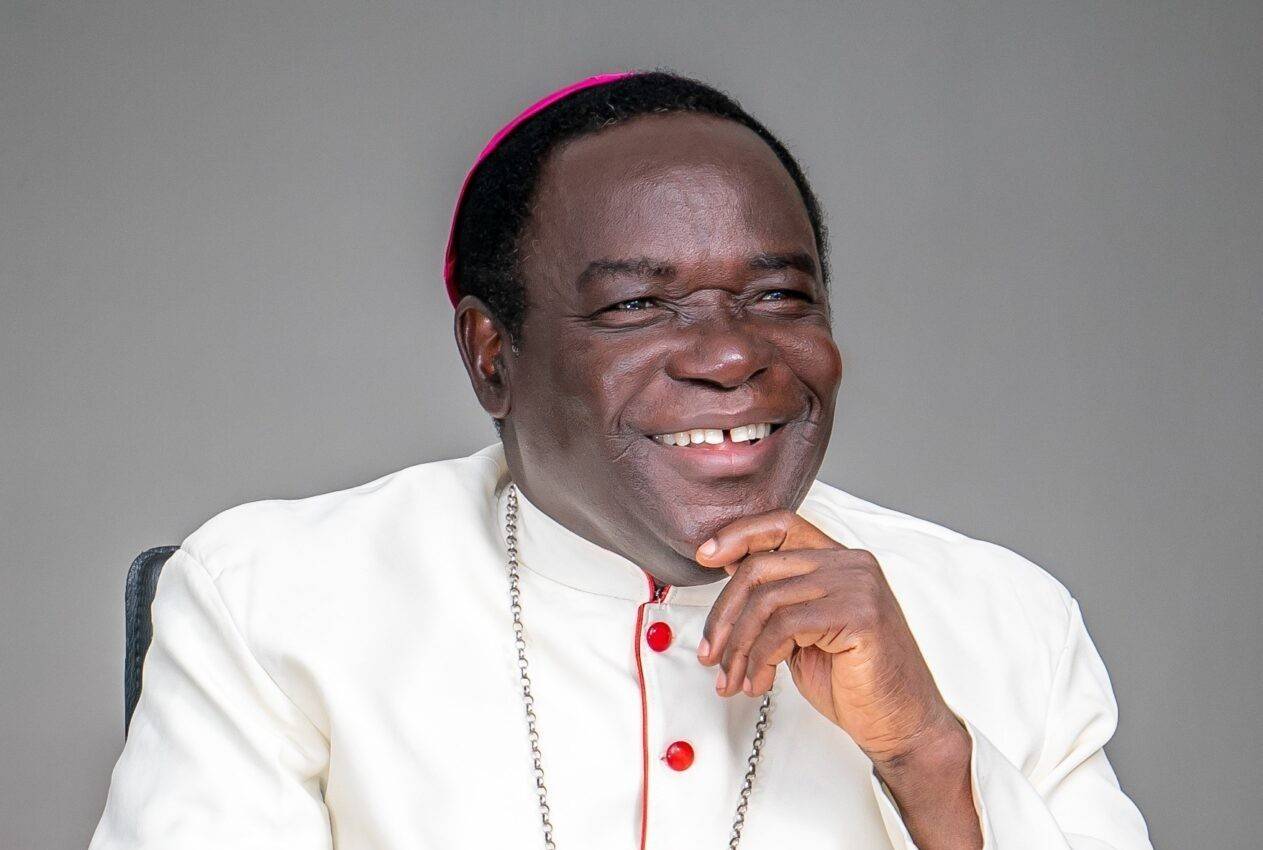

Archbishop Ignatius Kaigama of Abuja said the process begins with the understanding that traditional cultures have spiritual underpinnings that provide a basis for the encounter with Christianity.

“Inculturation, therefore, is the unqualified identification of the Gospel with the indigenous culture and its cultural values in which we discern the “seeds of the Word” (semina verbi),” Kaigama of Abuja told Crux.

The concept of inculturation in the Catholic Church became prominent during the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), which stressed the importance of engaging with diverse cultures to make the Gospel more accessible and relevant. A 1985 Synod of Bishops further emphasized inculturation as “the intimate transformation of authentic cultural values through their integration in Christianity in the various human cultures.”

Yet some observers today say that many priests are rushing to foster inculturation in Africa without a proper understanding of the cultural contexts, and how the Gospel message can help illuminate such cultures.

“I agree with this charge against these aberrant Catholic priests, because we are seeing very bewildering liturgical abuses in Nigeria in the name of inculturation,” said Father Stan Chu Ilo, Research Professor of ecclesiology and African studies at the Center for World Catholicism and Intercultural theology at DePaul University in Chicago and President of the Pan-African Catholic Network.

Chu said he doesn’t believe that priests “who introduce these bizarre practices can demonstrate how these rituals relate to any element of traditional African religious worship or African worldview. “

“We are witnessing a shocking liturgical hybridity and religious pathologies, in which some Catholic priests in Nigeria, and lay Catholics who claim extraordinary divine power, mix and mingle their own contorted cultural imaginations with confusing Pentecostal inventions that are all packaged to achieve maximum effect of attempting to validate themselves as healers, prophets and persons with extraordinary power,” Chu told Crux.

“These practices confuse the faithful and constitute a scandal of grave proportions,” he said.

Kaigama believes some of these conflicts arise from “obstacles to authentic dialogue between the faith and African culture.”

These obstacles, he said, include a colonial mindset where generations of Africans viewed their traditional cultures negatively as fundamentally opposed to Christianity, as well as a marked decline in local languages because many young people are growing up in families where little value is placed on the local language in favor of English, French, or Hausa.

Still, inculturation as an approach to evangelization remains a valid path to strengthening the Christian faith in Africa. Both Mbuy and Chu believe that more education is needed to bring Catholic priests up to speed on the best approach to evangelization.

“I think that the Church in Nigeria and the rest of Africa, particularly theologians and pastors, need to go back to the basics of deepening their understanding of African traditional religions, African spirituality, and African ethics of life,” Chu said.

“There are considered taboos in our traditions and some superstitious practices which we African Christians need to understand in order to find the best ways of inculturating them or rejecting them outright,” he said.

“It is not possible for real inculturation in any parish or diocese to take place unless we have had experts in both theology and the culture working together to provide a better understanding,” Mbuy said.

“The fact that we are playing the xylophone or beating the drum in the church, for example, is not necessarily inculturation. At best, it is adaptation, indigenization, or accommodation,” he said.

“For playing of xylophones and drums to become inculturation, we have to ask ourselves a series of questions and get the right answers. What does a drum or xylophone signify to a particular people? When and why do they use this particular instrument? The melody that we are adapting, how appropriate is it to liturgy? When do people traditionally use that particular rhythm which we intend to use? And what does that rhythm signify to the people?”

“These questions cannot be answered without the assistance of those who are deeply steeped in culture and who understand the situation of the people,” Mbuy said.

Chu said there is a need for a deep understanding of African Traditional Religions and the Christian traditions if inculturation is ever going to be effective.

“A deep understanding of both African Traditional Religions and Catholic traditions should be the starting point,” he told Crux.

“This understanding cannot be gained from the comfort of our chanceries, rectories and theologates. It requires doing ethnographic studies, going out to the peripheries to see the people’s pain and pathos, their sense of insecurity, the broken relationships, the failed government, and the double burden of diseases (infectious and non-infectious) in Africa that create in our people a sense of despair and a desperate search for God and for hope in all places including in the wrong places,” he said.

Chu called for better formation of religious authorities, as well as “a deepening of the faith and a better understanding of our Christian identity which is never opposed to our cultural identities.”

Kaigama said Africans can remain truly African and truly Christian, downplaying concerns of conflict between Christianity and African cultures.

“Africa is endowed with a wealth of cultural values, priceless human qualities, and cultural heritage which it offers to the Church and to humanity as a whole. There is, therefore, no doubt that inculturation will enrich our continent when faithfully embraced,” he told Crux.