WASHINGTON, D.C. — Participants at a Catholic-led conference on peace on the Korean Peninsula said it might be time to rethink how to engage with North Korea, because economic sanctions and displays of military strength have not deterred the country from aggressively pursuing a nuclear weapons development program.

Such a reset, conference speakers said, could renew cross-border exchanges between North Korea and South Korea, see the wider delivery of humanitarian aid to the North, lead to greater opportunities for family reunification and eventual reversal of widespread human rights abuses.

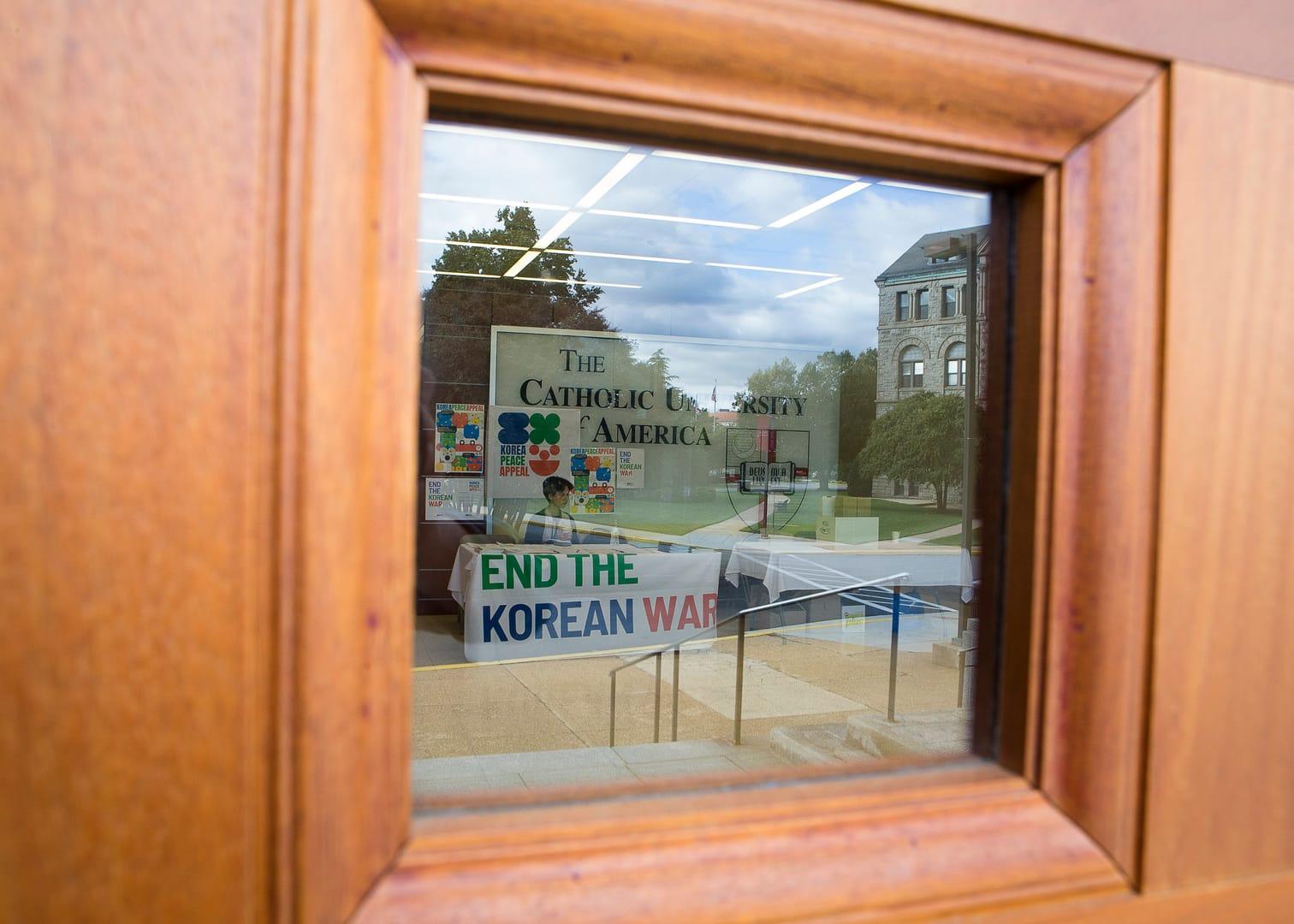

The Oct. 5-6 event at The Catholic University of America brought together leading advocates for peace in northeast Asia, including South Korean and American church leaders, representatives of nongovernmental organizations, and academic experts to explore ways to overcome the deep distrust of the North and its young leader, Kim Jong Un.

The threat of North Korea’s nuclear weapons program and what some called Kim’s unpredictability prevailed during the two days of discussions. Nearly to a person, attendees were wary of Kim’s expanding military goals — with six missile test launches since Sept. 24, including a flyover of Japan, and a possible nuclear test looming.

The annual series began in 2017, and presenters during the sixth conference said it was doubtful Kim would be willing to change course under threat from the United States. Instead, they called for creativity and widening the diplomatic field to include Japan and other nations in seeking to end 70-plus years of conflict.

Technically, the Korean War, which was fought from 1950 to 1953, continues. Fighting has remained on hold under a 69-year-old armistice. The Korean Demilitarized Zone is the most heavily armed border in the world.

South Korean bishops attending the conference stressed that the Catholic Church could play a major role as peacemaker in northeast Asia and be a bridge between North and South.

Bishop Peter Lee Ki-heon of Uijeongbu, South Korea, chairman of the Korean bishops’ Committee for the Reconciliation of the Korean People, said the church’s moral call for peace must be unrelenting in the ears of policymakers.

While the Catholic Church in North Korea “practically has become vacant,” he said it has not disappeared, and he called for persistent outreach from the church to political leaders.

“Advanced weapons, including nuclear weapons, are being developed, and the resulting risk is on the rise, which necessitates greater needs for a diverse voice about war and peace,” Bishop Lee told the conference.

Archbishop Timothy P. Broglio of the U.S. Archdiocese for the Military Services praised the efforts of the South Korean Catholic Church to continue seeking peace at a time of escalating tensions.

During a 2018 visit to South Korea, he said, he found that the bishops were unanimous “in recognizing the crisis on the Korean Peninsula cannot be resolved by military means alone.”

“Focusing only on the military response readily amplifies the arms race, exacerbating tensions and directing much-needed resources away from the root causes of the conflict: fear of the other and what they can do to threaten the survival of each side’s way of life,” he said.

The U.S. archbishop was among the speakers who noted that economic sanctions “do not seem to have made much difference” on Kim’s nuclear ambitions, and he said it was “time to look at other options.”

The conference also heard from an official from the U.S. State Department and another from South Korea’s Ministry of Unification.

Scott Walker, director of the Office of Korean and Mongolian Affairs at the State Department, said recent overtures by the U.S. directly to Kim and through back channels have been ignored.

North Korea has maintained a lockdown of its borders because of the COVID-19 pandemic, further isolating the country from the world. Walker said the lockdown and Kim’s deeper alignment with China and Russia in recent months pose concerns for the U.S.

The official held out hope that “we can find a peaceful and diplomatic solution with the DPRK,” the initials for the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, North Korea’s official name.

He added that “the United States harbors no hostile intent toward the DPRK and is willing to engage in dialogue with Pyongyang without preconditions.”

Byoung-Sam Koo, director of policy planning at the Korean Ministry of Unification, said South Korea envisions a “denuclearized, peaceful and prosperous Korean Peninsula for peaceful unification that is built upon free and democratic order.”

He laid out principles that the South Korean government under President Yoon Suk-yeol, who took office in May, views as necessary to unification including intolerance for military provocation, resolving differences through dialogue, and establishment of a foundation for unification based on confidence.

The diplomats’ comments were politely received, but the responses of conference participants throughout the two days indicated that efforts outside of official diplomatic circles are needed to build a foundation for peace.

Byun Jin Heung, chief researcher at the Catholic Institute of Northeast Asia Peace, which sponsored the conference with the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, suggested the United States’ recent invitations to the Kim government are too limited.

“An open window is not enough. … We have to build a bridge that allows them to come across and have a discussion,” he said.

“It could be religious leaders who start the conversation. It could be small steps. It doesn’t have to be big right now,” he added to applause during the conference’s closing discussion.

The 2023 conference is being planned for Japan, the first time it will be held in that country, according to conference organizers. It was suggested by at least two participants that an invitation be extended to North Korea to send representatives, allowing for broader participation.