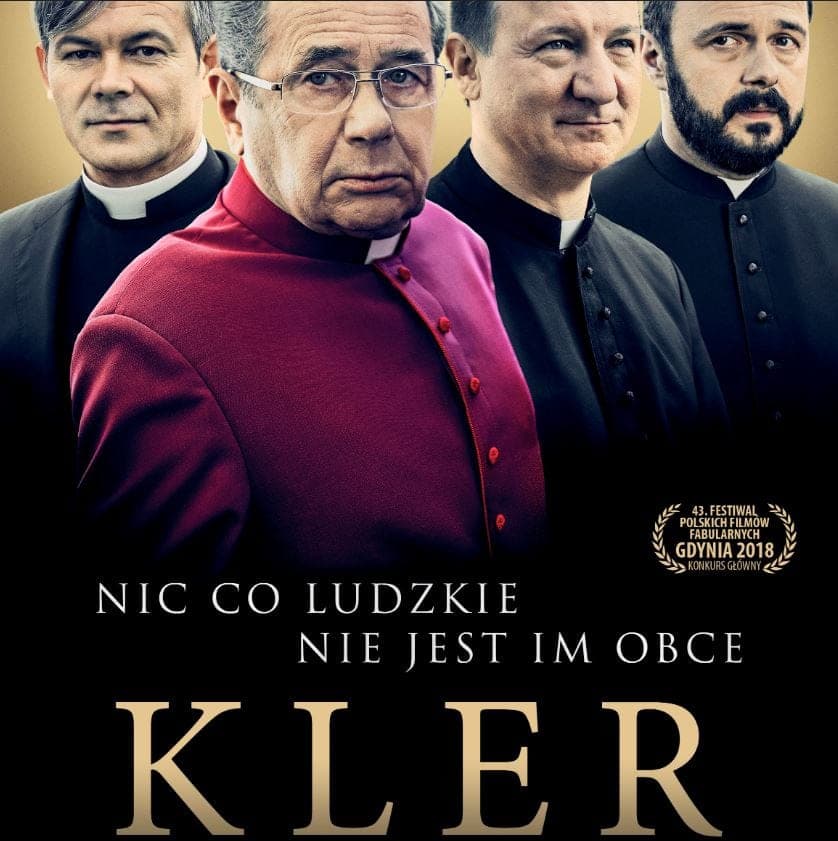

The Polish film Kler – “Clergy” in English – has all the elements of a blockbuster: A top-notch director, a casting with many of the well-known stars of the Polish film industry, and a racy plot on a global issue: The story of three priests with all possible skeletons in the closet – alcohol, women, pedophilia, money and politics.

The film opened on Sept. 28, and in its first weekend of exhibition, close to a million Poles flooded cinemas to watch it, breaking a 30-years-old record in the country. Its success came as a surprise, considering that Poland is the most Catholic country in Europe, and the bishops still have a lot of influence and authority among their fellow citizens. Many clerics had strongly condemned the film.

“Kler is a false image of the Church,” Father Dariusz Kowalczyk, a Polish Jesuit teaching at Rome’s Pontifical Gregorian University, told the Polska Times.

Kowalczyk added that the director “does not have an idea about the Church neither from the point of view of the altar, nor from the side of the sacristy.”

“It’s vulgar clergyphobia,” he said.

His views were shared by many Polish priests on social media, although there hasn’t been an official statement from Poland’s bishops’ conference.

However, politicians haven’t been as reticent to comment on the film.

Representatives of the conservative Law and Justice Party now running the country condemned the film, and the right-wing Gazeta Polska newsweekly referenced the film on the cover of its latest issue: It said ‘Kler’ but featured priests who are national heroes in Poland: Pope St. John Paul II, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński,, Saint Maximilian Kolbe and Blessed Jerzy Popieluszko.

Even the Catholic Association of Journalists harshly criticized the film and called for a boycott.

These condemnations did little to deter the crowds.

Father Marek Lis, a film critic and professor at the Opole University, said strong criticism might be helping the movie.

On his Twitter account he wrote: “Let me be crystal clear: With unthoughtful protests, we are just advertising the movie.”

Before the movie’s premiere, Lis sent a suggestion to the Polish Episcopal Conference: “In many cases we need to agree with the authors of a controversial movie. Many times in the past, an artistic expression provided explanation and put in the spotlight something that the Church wanted to keep silent about.”

Father Michał Legan, a communications professor at Pontifical University of John Paul II in Krakow, said similar reactions happened when the films Spotlight and Bad Education hit the movie theaters.

“We need to step into dialogue with filmmakers who raise serious concerns, even though they’re tough,” Legan said.

Especially in a country where over 90% of Catholics churches were still fully packed on the opening weekend of the film, a fact that wasn’t changed by the premiere of the movie.

Father Tomasz Szopa, the chancellor of the Archdiocese of Krakow, said on Twitter: “The attendance of the movie everybody is talking about this weekend was 1 million. That very Sunday, 5 million people received communion in our churches.”

Lis said the Church must help set the narrative when a film comes out which could put the Church in a bad light.

“We can answer to movies like that with protests and outrage. That way surely we will boost the attendance in cinemas, which exactly happened, even before we saw the movie,” the priest said.

Lis says there are three major steps a Church communicator needs to take while answering a controversial movie: First, prepare and see the movie and do not react based on your initial emotions; second, avoid a naïve analysis – there are problems in the Church, and the Church has to be prepared to face them; third, remember a movie is an artistic interpretation, highly exaggerated and the Church’s reaction should not be overblown.

“It is only a movie after all and reacting to it as if the pope himself was responding to the director doesn’t seem appropriate at all,” he said.

An interesting example is how Opus Dei, a personal prelature within the Church, reacted to the book and film The Da Vinci Code.

In the work, a murderous “albino Opus Dei monk” kills people on behalf of the prelature to block the unveiling of the “true” marital relationship between Jesus and Mary Magdalene.

A team of professors from the Opus Dei-run Pontifical University of the Holy Cross in Rome designed a communications strategy which took advantage of the notoriety to explain what Opus Dei really was.

Its motto was “turn lemons into lemonade” and used the notoriety of the film to run an information campaign both on Opus Dei and the historical truths of Jesus.

In many ways, this helped Opus Dei itself become more transparent – its secretive nature was one of the reasons novelist Dan Brown chose the organization for his albino monk.

Professor Juan Manuel Mora was the leader of the media team.

In a case study he wrote on the subject, he remembered the words the then-Prelate of Opus Dei, Blessed Alvaro del Portillo, told him to inspire their reaction to the movie: “The strategy of the three Ps –positive, professional and polite, with a recommendation of a fourth ‘P’ for patience.”