ROME – On Tuesday a collective of Catholic groups in Italy criticized the Church in Italy’s inability to reckon with the clerical sexual abuse crisis and called for an independent national inquiry like those being done in other European countries.

Speaking during a Feb. 15 press conference on the launch of the appeal, Ludovica Eugenio, head of the digital weekly, Adista, which covers Catholic and religious news, said that ever since the Boston Globe’s Spotlight investigative team unveiled the extent of clerical sexual abuse in the United States, “it has been increasingly difficult to ignore the problem.”

While largescale, in-depth inquiries have been made in countries such as France, Germany, Ireland, the United States, Portugal, and now Spain, in the pope’s own backyard, “nothing is happening,” Eugenio said.

In Italy, priests, she said, are still seen as “sacred and untouchable” while victims’ lives “have been devastated in unspeakable ways.”

Eugenio’s Adista is one of nine groups, seven of which are led by women, who joined in issuing the demand for an inquiry during Tuesday’s launch of a campaign titled, “Beyond the Great Silence,” which is being promoted on social media with the hashtag, #ItalyChurchToo, inspired by the global #MeToo movement against sexual harassment.

The campaign seeks to increase public pressure on both the leadership of the Catholic Church and the Italian government for a formal independent national inquiry into clerical sexual abuse going back decades.

Paola Lazzarini of the Donne per la Chiesa organization said Tuesday asked that an investigation be launched “as soon as possible,” and that it be led by an independent party with the necessary qualifications.

She also asked that it use both “qualitative and quantitative methods of documentary analysis,” which goes against a current proposal put forward by the head of the Italian bishops’ conference (CEI), Cardinal Gualtiero Bassetti of Perugia.

With so many other European nations conducting inquiries, Italian bishops themselves are currently pondering the idea, which will be decided on after the election of Bassetti’s replacement during their spring assembly in May.

Bassetti, whose tenure leading the Italian bishops will come to an end once his successor is named, has insisted on a “qualitative” inquiry rather than a quantitative one, and said the conference as a whole, which is currently divided on the issue, must agree to it.

The current proposal being discussed by CEI would draw on data from a new program at the diocesan level for listening to victims, which is run by CEI and religious superiors.

In her remarks, Lazzarini said that because this program is not independent, “that can’t be a source of data,” and voiced hope that with the change in CEI’s leadership in May, the bishops will “come to a different proposal.”

Lazzarini also asked that the archives of “all dioceses, convents and monasteries” be opened in order to uncover the truth, “however painful.”

She also pushed for compensation for victims and stressed the importance that the inquiry be focused “exclusively on the reality of abuses in the Italian Catholic Church” in order to paint a clearer picture and, in her view, create a model that can be replicated in other educational institutions and agencies.

Yet victims and advocates participating in Tuesday’s launch believe the path to a formal inquiry in Italy is an uphill battle given the outsized political, economic, and social influence the Church still carries in Italy.

“Here, there is a situation of stall,” said Francesco Zanardi, a survivor of clerical abuse and founder of the Rete L’Abuso (The Abuse Network), which tracks cases of clerical abuse.

Given the weight the Church carries in Italy, Zanardi said prosecutors have been reluctant to investigate clerical abuse cases, and requests for parliamentary inquiries have gone unanswered. There is also a general disinterest from the public, a large percentage of which allocate funds to the Church through Italy’s tax system.

Organizers of Tuesday’s campaign voiced belief that the Catholic Church in Italy is unprepared and unwilling to face the consequences a national inquiry would inevitably yield, as revelations of clerical abuse globally have cost the Church hundreds of millions in litigation and compensation to victims.

According to Zanardi, if a serious inquiry were done in Italy, the fallout would likely be more severe, as the figures would likely be much higher since Italy is a predominantly Catholic country that has far more priests than its European neighbors.

A German study published in 2018 found that 1,670 priests abused some 3,677 minors from 1946 to 2014. An investigation in France released last year and spanning seven decades found that more than 200,000 children were abused in Catholic institutions.

Zanardi said his organization has identified at least 360 cases in the past 15 years, and insisted that “state intervention is needed.”

Efforts by Pope Francis, including the publication in 2019 of the law Vos Estis Lux Mundi, which requires mandatory reporting for bishops, “have proven useless,” Zanardi said, because laws such as this are not applied.

“Bishops don’t obey the laws but they aren’t punished. Weak laws have favored the transfer of pedophiles to Italy,” he said. Even if the perfect Church commission were established, it “is no longer credible,” he said, adding, “We need an independent one that ensures impartiality. The accused cannot also act as judge.”

Any Italian investigation, he said, “absolutely has to be impartial” if it is to be effective.

What victims had to say

Several alleged victims also spoke during Tuesday’s press conference, backing the call for an independent national inquiry and criticizing Church failures in their own cases.

Cristina Balestrini of the Committee of Victims and Families section of Rete L’Abuso, said she is the mother of a victim of clerical abuse and, after seeing the impact the abuse had on her own child, decided to offer support to parents of other victims through her organization.

“Only those who have been through it can understand deeply what a family that has suffered this drama experiences,” she said, adding, “What does not come out in the news is the after, the fatigue of carrying a boulder that is not resolved after the act of violence.”

The Catholic Church in Italy, Balestrini said, “Has no competence with regard to the management of abuses, nor from a legal point of view” in terms of bringing a guilty priest to justice and obtaining compensation and psychological support for victims.

Balestrini, who remains a Catholic, said that in her experience, “The Church does not protect the victims; rather, even in civil courts, the Church defends the priest, not the victims.”

“We have experienced this in our own skin,” she said, recalling how some time after her child was abused, they approached their pastor about it, voicing their desire to pursue justice. The pastor, she said, told them “Not to spit on the plate we eat from.”

In response, Balestrini said she told the pastor that, “for ten years we have been trying to empty that dish of the vomit we smell.”

Erik Zattoni, 40, said his mother was raped by a priest when she was 14, and he was born as a result of the assault.

He said that when his mother first tried to denounce the rape, she was instructed by the bishop not to tell anyone about it, because “it would be a great scandal for the Church.”

Nothing was ever done, and this man “died as a priest,” Zattoni said, saying that while he is not a victim himself, “my mother is and I see it in her eyes every day; her life has never been the same since that moment.”

Zattoni admitted that at times, he feels “ashamed” when his mother sees him, “because I know I remind her of that moment, I know I’m the son of a rape.”

“I consider myself an indirect victim, it is important to let people know that we are here too, it’s important not to forget us,” he said, and stressed the need to “act in an important and decisive way” when cases come up, “otherwise nothing will ever change.”

A man named Antonio Messina said he was abused while a minor from 2009-2013 by an adult seminarian who later became a priest while he was discerning his own possible call to the priesthood – a discernment Messia believes put him in a vulnerable position and opened the door for the abuse to happen.

There was a psychological coercion “often difficult to recognize” in the abuse, Messina said, saying he complained a year after his abuse ended, once he realized what had happened, but when he told his spiritual director about it, he was told to just leave his city and “forget about it.”

Without going into detail, Messina said Church leaders in his hometown tried to buy his silence with funds from the diocesan Caritas fund, and the priest was eventually transferred to another diocese.

“The Church is unable to address this (investigation),” he said, but if an independent inquiry is held and “if we can make sure that this does not happen to others, these bad stories can at lease serve to change something in the Church and in society.”

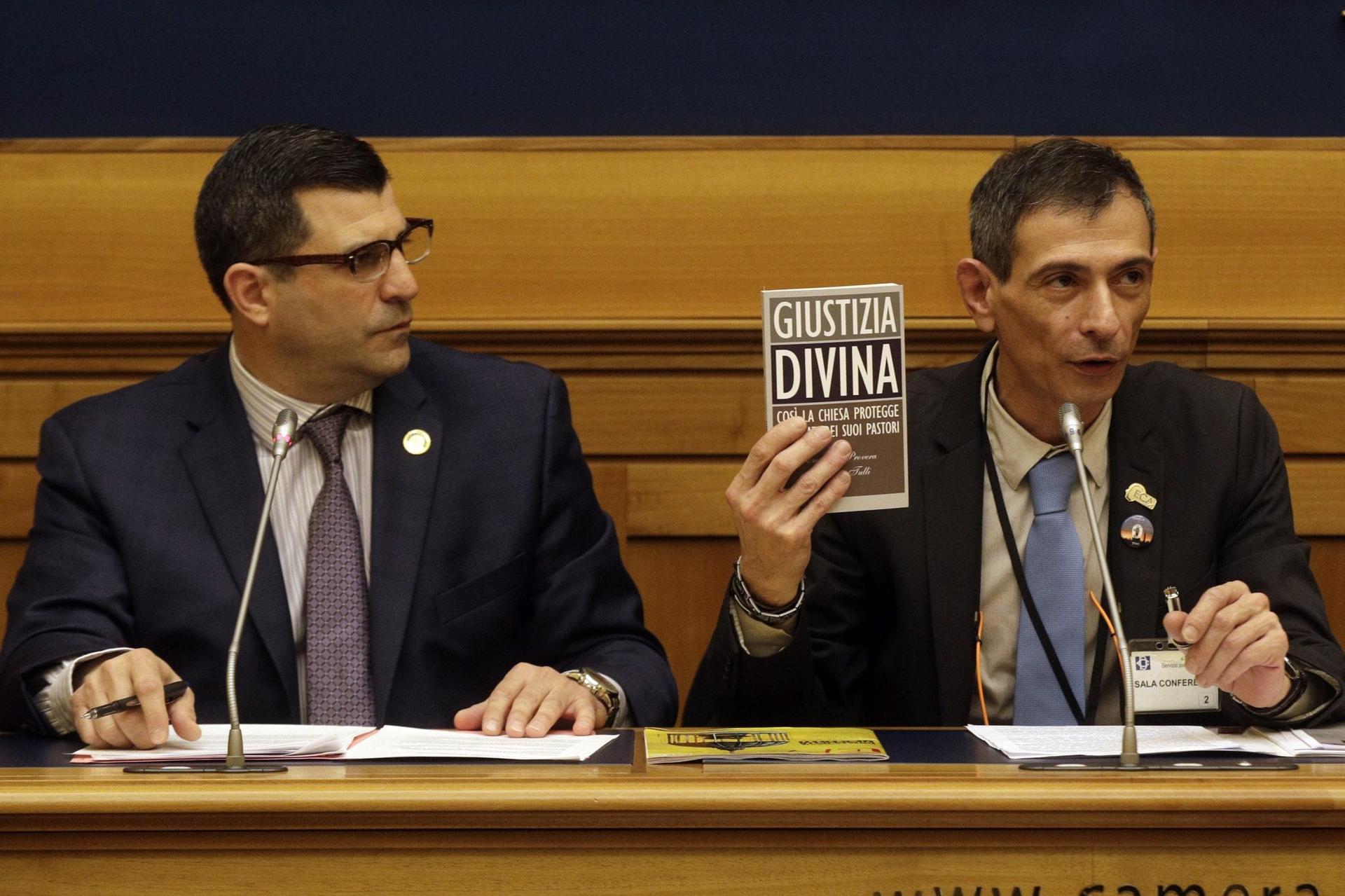

Francesco Tulli of Italian weekly Left said his paper this week is launching a database to track cases of the abuse of minors in the Church with the collaboration of Rete L’Abuso, which he hopes will be of use if an inquiry is launched.

In her remarks, Eugenio said the problem of clerical abuse and the fight to end it must be taken as “a sign of the times,” and that for progress to be made, “the Church itself must take action.”

Follow Elise Ann Allen on Twitter: @eliseannallen