In secular politics, especially for prime ministers and their governments in countries with parliamentary systems, and to a lesser but still significant extent for presidents and their new administrations, 100 days is a major marker.

Their governments are formed, their major appointments are made, their policy agenda set and in the works. Their terms of office are supposed to have direction by the 100-day mark, and it is time to get down to brass tacks.

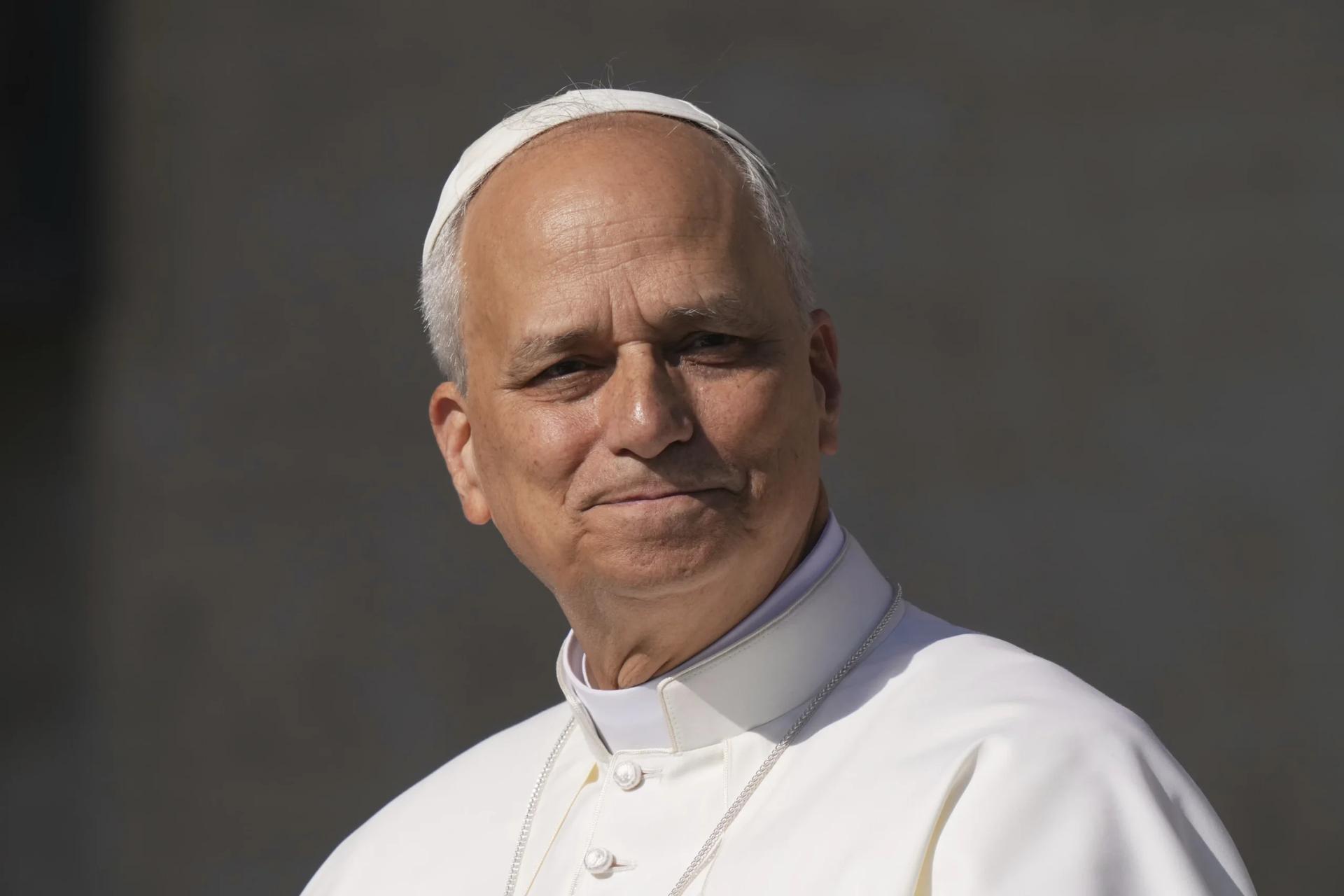

Pope Leo XIV hit the milestone this weekend, marking 100 days since he took office on May 8, but there was no fanfare from the Vatican.

That is not surprising.

For one thing, Rome is pretty empty for the ferragosto holiday and the pope is in Castel Gandolfo, the second stint of the season for Leo at his summer retreat.

For another, the papal office is very different in both purpose and scope, from that of a prime minister or a president (or even a secular monarch).

The papacy is an office of government, but its role in the life of the Church is primarily to safeguard the Church’s teaching and guarantee good order and harmony of life within the Church and among the faithful.

Leo has given some indication, at least, of how he intends to govern.

“I come to you as a brother,” Leo said in his homily during Mass on May 18, to mark the beginning of his pontificate, “who desires to be the servant of your faith and your joy, walking with you on the path of God’s love, for he wants us all to be united in one family.”

“Love and unity,” Leo said, “these are the two dimensions of the mission entrusted to Peter by Jesus.”

In his inaugural homily, Leo may well have been more programmatic in his remarks than it appeared at first blush. He spoke of the abundance of discord and hatred, violence, fear –especially the fear of difference — and the wounds they have caused and continue to cause.

Channeling Francis, Leo spoke of “an economic paradigm that exploits the Earth’s resources and marginalizes the poorest.”

“For our part,” Leo said, “we want to be a small leaven of unity, communion and fraternity within the world,” all three things – unity, communion, and fraternity – cornerstones of the Gospel and keystones of the Augustinian spirituality in which Leo has been formed.

“We want to say to the world, with humility and joy: Look to Christ! Come closer to him!” Leo preached. “Welcome his word that enlightens and consoles!” he said.

“Listen to his offer of love and become his one family,” Leo said, and then offered his episcopal motto: “In the one Christ, we are one.” In illo uno unum.

Leo’s first hundred days have not seen him make any monumental changes, either in law or policy or personnel. They have been, with apologies to Warren G. Harding, “a return to normalcy.”

(An Ohio Republican, Harding made the expression a slogan of his 1920 presidential campaign, which he won in a landslide victory over James Cox, also of Ohio. Harding, by the way, was not exactly a political unknown but was fairly a dark horse candidate who got the Republican nomination as a compromise acceptable to both the conservative and progressive wings of the Republican Party.)

That’s not to say Leo hasn’t made an impression.

His impromptu evening jaunt around St. Peter’s Square and off-the-cuff remarks to thousands of young people gathered for a welcome Mass at the opening of the Jubilee for Young People galvanized his audience.

“You are the salt of the earth,” Leo told the young people, “the light of the world! And today your voices, your enthusiasm, your cries — all of them for Jesus Christ — will be heard to the ends of the earth!”

Days later, at a vigil and again at the Mass concluding the Jubilee for youth, Leo again thrilled crowds estimated at a million strong in Rome’s Tor Vergata park.

Francis’s maverick style was intensely personal and released enormous energy, but where Francis was explosive, Leo tends rather to focus – on Christ – and to concentrate energy.

Leo will have to govern, sooner or later.

Expect things to happen fairly quickly when he does, but expect Leo to be methodical, precise, and especially to have his ducks in a row when he acts.

The next hundred days, and the hundred days after that, are the ones to watch.