ROME – When news broke that Vladimir Putin had ordered the Russian troops to invade Ukraine, Deacon Daniel Galadza was in Rome taking part in a conference at the Vatican’s Congregation for Eastern Churches.

Six days before the war, on Friday, conference participants were welcomed by the pope, who said he regretted the fact that humanity seems “attached to wars, and this is tragic.”

RELATED: Pope decries warmongering, prays for Eastern Catholics in danger

Galadza is a deacon of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC), and even though he had some reservations about being ordained instead of remaining an academic, one could argue the church was in his blood: “My father was a Ukrainian Catholic priest, my uncles were Ukrainian Catholic priests, and my great grandfather was a Ukrainian Catholic priest, who got a free ticket to Siberia thanks to Stalin, and took his wife and daughters.”

Galadza was born in the United States but grew up in Canada. He studied in Rome, but worked in Vienna until, “because I am naïve and an idealist,” he quit his job to move to Ukraine, where he was encouraged by the church to continue his academic formation. Now in Germany, finishing his second doctorate, he has plans to relocate to Rome next semester.

Even though he wasn’t supposed to go back to Ukraine after the Vatican conference, his heart is very much in his homeland.

“I was in Ukraine in December, and the discussions amongst priests in the sacristy of our cathedral spoke of the courage these people have,” Galadza said. Even though everyone hoped Putin would not go through with the invasion of Ukraine, he said being there one understands why this is “a church of martyrs,” one that, just a generation ago, was “suffering in the catacombs.”

And even in the face of a threat they know all too well, according to the deacon, Ukrainians were still able to hold onto their sense of humor, a sign of their resilience and faith.

Calling the UGCC a Church of martyrs is not, by any means, an exaggeration.

In the Soviet era, the UGCC was the largest illegal religious body in the world and suffered mightily for it; most experts believe the total number of Greek Catholics who perished in that era of violent oppression is in the thousands.

After Communism, the church experienced a rebirth: After driving 3.5 million faithful underground and confiscating almost all of its property, a post-Soviet Ukraine allowed the UGCC to reemerge. From that point, it rose from the catacombs with miraculous growth.

Over 3,000 priests died in the gulags, and by the time Ukraine regained its independence, only 300 were left, and not all of them in Ukraine. Today, this church claims more than 7 million faithful and 3,000 priests, with 100 being ordained each year and more than 800 seminarians.

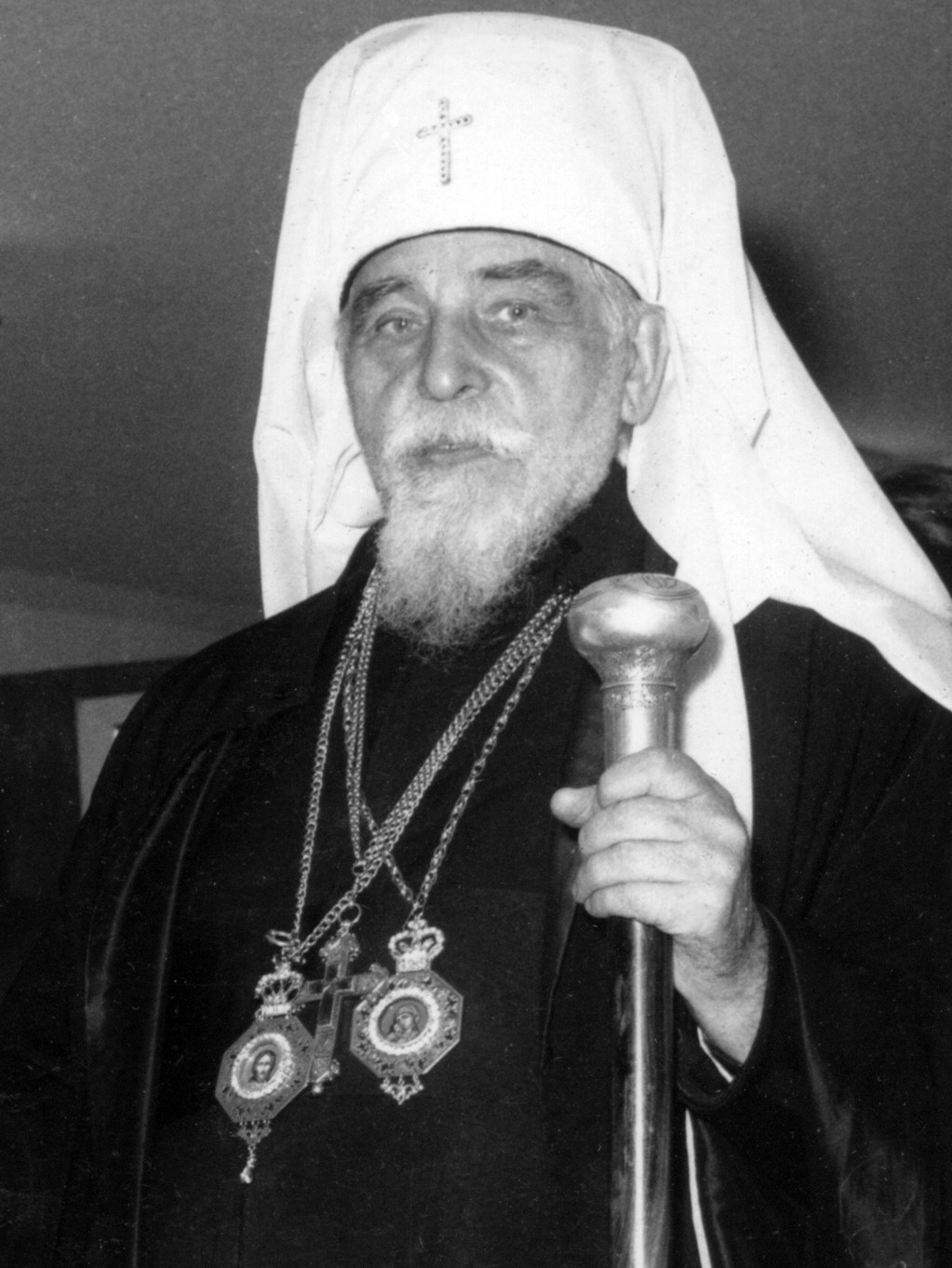

The legendary Ukrainian Cardinal Josef Slipyi, who spent two decades in the gulags, once said that his church had been buried under “mountains of corpses and rivers of blood.” During his 2001 visit to Ukraine, John Paul II beatified 27 Greek Catholic martyrs under the Soviets — one of whom had been boiled alive, another crucified in prison, and a third bricked into a wall.

The UGCC has long been among the most important pro-democracy forces in Ukraine, trying to galvanize the Western powers to stand up to Russian aggression, which helps explain why Major Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk speaks about faith, along with a little bit about politics, during his daily videos sent from an underground shelter in the Patriarchal Cathedral of Christ’s Resurrection in Kyiv.

After thanking Pope Francis for “sharply and unequivocally condemning the war against Ukraine” during Sunday’s Angelus prayer, in Monday’s video, he called on the world to “close the sky over Ukraine,” something the Ukrainian president has been asking NATO nations to do. This, according to Putin, would be an act of war.

Follow Inés San Martín on Twitter: @inesanma