WIEJKOWO, Poland — More than 1,000 years after his death in what is now Poland, a European king whose nickname lives on through wireless technology is at the center of an archaeological dispute.

Chronicles from the Middle Ages say King Harald “Bluetooth” Gormsson of Denmark acquired his nickname courtesy of a tooth, probably dead, that looked bluish. One chronicle from the time also says the Viking king was buried in Roskilde, in Denmark, in the late 10th century.

But a Swedish archaeologist and a Polish researcher recently claimed in separate publications that they have pinpointed his most probable burial site in the village of Wiejkowo, in an area of northwestern Poland that had ties to the Vikings in Harald’s times.

Marek Kryda, author of the book “Viking Poland,” told The Associated Press that a “pagan mound” which he claims he has located beneath Wiejkowo’s 19th-century Catholic church probably holds the king’s remains. Kryda said geological satellite images available on a Polish government portal revealed a rotund shape that looked like a Viking burial mound.

But Swedish archaeologist Sven Rosborn, says Kryda is wrong because Harald, who converted from paganism to Christianity and founded churches in the area, must have received an appropriate grave somewhere in the churchyard. Wiejkowo’s Church of The Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary stands atop a small round knoll.

Historians at the Danish National Museum in Copenhagen say they are familiar with the “suggestion” that Wiejkowo is Harald’s burial place.

Rosborn detailed his research in the 2021 book ”The Viking King’s Golden Treasure” and Kryda challenged some of the Swede’s findings in his own book published this year.

Harald, who died in 985, probably in Jomsborg — which is believed to be the Polish town of Wolin now — was one of the last Viking kings to rule over what is now Denmark, northern Germany, and parts of Sweden and Norway. He spread Christianity in his kingdom.

Swedish telecommunications company Ericsson named its Bluetooth wireless link technology after the king, reflecting how he united much of Scandinavia during his lifetime. The logo for the technology is designed from the Scandinavian runic letters for the king’s initials, HB.

Rosborn, the former director of Sweden’s Malmo City Museum, was spurred on his quest in 2014 when an 11-year-old girl sought his opinion about a small, soiled coin-like object with old-looking text that had been in her family’s possession for decades.

Experts have determined that the cast gold disc that sparked Maja Sielski’s curiosity dated from the 10th century. The Latin inscription on what is now known as the “Curmsun disc” says: “Harald Gormsson (Curmsun in Latin) king of Danes, Scania, Jomsborg, town Aldinburg.”

Sielski’s family, who moved to Sweden from Poland in 1986, said the disc came from a trove found in 1841 in a tomb underneath the Wiejkowo church, which replaced a medieval chapel.

The Sielski family came into the possession of the disc, along with the Wiejkowo parish archives that contained medieval parchment chronicles in Latin, in 1945 as the former German area was becoming part of Poland as a result of World War II.

A family member who knew Latin understood the value of the chronicles — which dated as far back as the 10th century — and translated some of them into Polish. They mention Harald, another fact linking the Wiejkowo church to him.

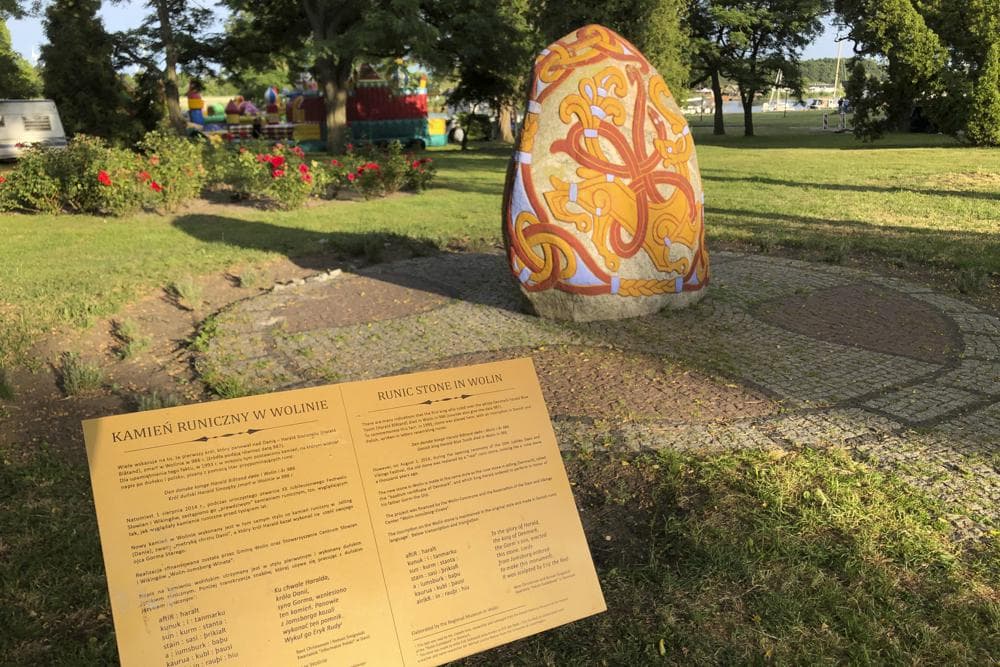

The nearby Baltic Sea island and town of Wolin cultivates the region’s Viking history: it has a runic stone in honor of Harald Bluetooth and holds annual festivals of Slavs and Vikings.

Kryda says the Curmsun disc is “phenomenal” with its meaningful inscription and insists that it would be worth it to examine Wiejkowo as Harald’s burial place, but there are no current plans for any excavations.